A kaleidoscope of simplicial arrangements

I think I've finally figured out the construction for an infinite family of pseudolines, described in Grünbaum's book using a single figure and no references. Along the way, I've found a nice physical experiment one could perform to generate these figures.

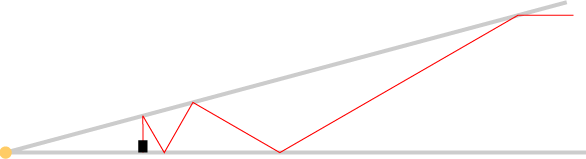

Suppose you have an apparatus consisting of two mirrors, hinged together, and a laser attached perpendicularly to one of the mirrors. Suppose also that there's enough vapor in the air to make the laser beam visible:

If you look into this from the side, it will act like a kaleidoscope, so that you see not just the wedge between the two mirrors and the beam within that wedge, but reflected copies of the wedge and beam. The reflected copies of the beam will match up with the real beam to look like lines, and if the angle of the wedge is of the form \( \pi/k \) for some integer \( k \), the wedges will link around evenly to cover the plane:

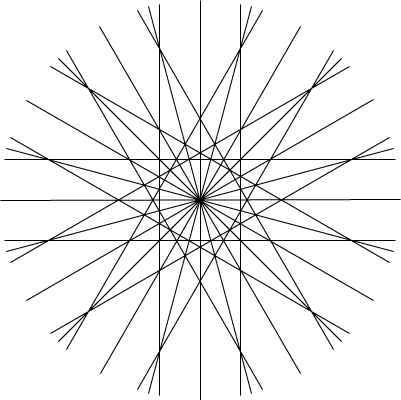

Here I've drawn the case for \( k=12 \), also drawing lines for the mirrors and their reflected images. It's our old friend, the simplicial arrangement R(24).

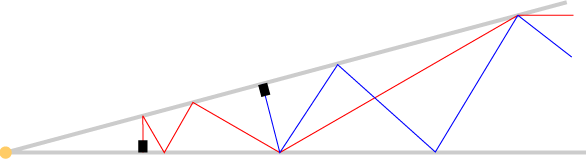

Now, add another laser, starting farther out on the other mirror, so that every third bounce of the second laser hits the same sequence of reflection points as every bounce of the first laser, and so that its final bounce is one step after the final point of reflection of the first beam. Actual light won't do this correctly (the angles aren't quite right) but you can fake it by using a piece of thread instead and tacking it down to the mirror at the appropriate points.

Looking at this second beam in the kaleidoscope, interleaved with the first one, produces a more complex arrangement:

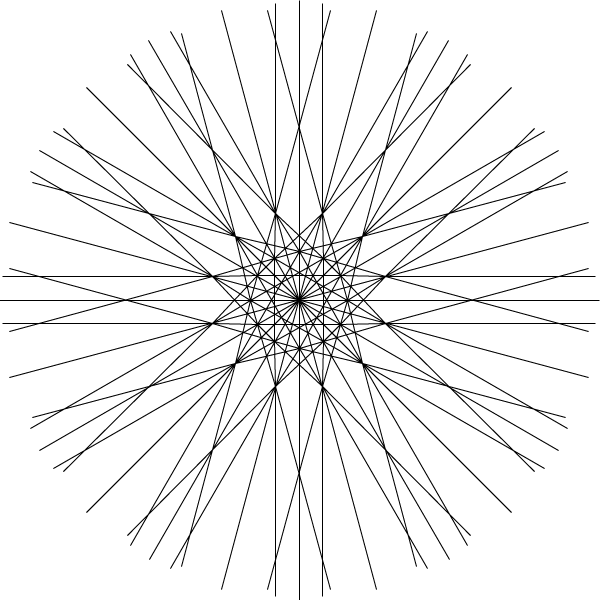

If the line at infinity is included, this forms a simplicial arrangement with \( 3k+1 \) lines, whenever \( k=0 \) or \( 4\bmod 6 \). It's an arrangement of pseudolines rather than lines because of the incorrect reflection angles of the second beam. In connection with the construction of cubic partial cubes from arrangements, I think this is interesting, not only because it provides yet another infinite family of arrangement-based partial cubes, but also because it looks like we can glue this arrangement to a rotated copy of itself to provide an infinite family of cubic partial cubes that do not come directly from a single arrangement. But I'm not yet sure how to prove that the result of this gluing operation is always itself a partial cube...

Other infinite families, described in the subsequent figures of Grünbaum's book (3.16 and 3.17; the one above is fig.3.15) follow similar principles, but with the second beam's laser attached to the same mirror as the first, with and without the line at infinity, or with odd values of \( k \).

Comments:

2005-11-23T07:57:33Z

*

awesome!

*

2007-01-15T20:59:20Z

I really like this kaleidoscope method of constructing these arrangements (it's not at all how I think about constructing them), but I wonder why you are restricting \( k \) to be congruent to 0 or 4 mod 6. It seems (ok, based on one example with \( k=20 \)) that it should work whenever \( k \) is even (although of course you need more laser bounces). What goes wrong?

Leah Berman

2007-01-16T05:39:56Z

If you line up the blue and red lasers so that the outer parts match up as in the illustration, with as before three blue laser reflections for every one red reflection, then the segment of blue laser beam between the laser and the mirror ends up crossing the red beam in the middle of the kaleidoscope instead of at a reflection. As a result you get a quadrilateral in the kaleidoscope, just inwards of the blue laser, bounded by part of a blue beam, parts of two red beams, and by the mirror. So it's not simplicial any more.

Try drawing it yourself with one more bounce than I've shown in the drawing — six bounces before going outwards, rather than the five in the figure.

2005-09-29T22:25:27Z

That's really cool!