Another partial cube of partitions

It turns out to be easier than I thought to make a partial cube out of all the partitions of \( n \) (and not just the binary partitions, as I did last time): simply make two partitions adjacent if one can be formed from the other by decrementing one of its values (removing the value if it reaches zero) and incrementing its largest value.

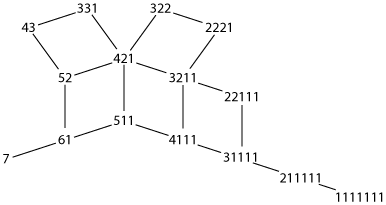

Here are the partitions of seven, drawn as a planar graph with symmetric faces (any graph with such a drawing is a partial cube):

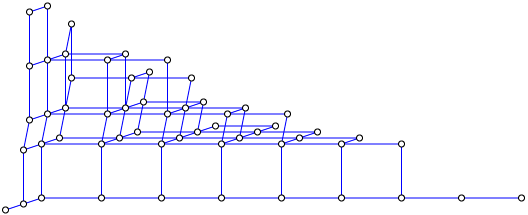

And here is a larger graph of the partitions of eleven; note the similar overall shape, with a short tail on the lower left for the trivial partition 11 and a longer tail on the right ending in the partition 1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1.

To show that these graphs are partial cubes, it's easiest to give the vertices labels that are \( (n-1) \)-dimensional integer vectors instead of bitvectors. The label of a partition is formed very simply, by dropping its largest value, keeping the sorted sequence of remaining values, and padding with zeros to give the correct number of coordinates. So, e.g., for partitions of seven, the partition 3+2+1+1 would have coordinates (2,1,1,0,0,0).

Each of the operations we use to connect adjacent partitions changes these coordinates by one, so the graph distance is at least equal to the L1 coordinate distance. Conversely, to connect two partitions by a path with length equal to their coordinate distance, line the values of the two partitions up, both in sorted sequence, find the last position where the two partitions differ, decrement the larger value at that position, and continue in the same manner with the resulting pair of partitions until we reach two equal partitions.