Partial cubes from binary partitions

I'm continuing to think about integer partitions.

In my previous posting, I described a tree structure on partitions, based on an operation that replaces the largest two values in a partition by their sum (turning, e.g., 5+2+2+1 into 7+2+1). What if, instead of the largest two values, we allow the merger of any two consecutive values (e.g., 5+2+2+1 ⇒ 5+4+1)? The connections between pairs of partitions related by this more general operation form a graph instead of a tree. What does this graph look like?

At least for binary partitions, there's a nice answer: the graph is a partial cube. That is, its vertices can be labeled by bitvectors in such a way that the graph distance between any two vertices equals the Hamming distance between their labels. To assign a bitvector to a binary partition, list its values in sorted order, and put a one in the \( i \)th bit of the bitvector whenever \( i \) occurs as the sum of one of the prefixes of the partition. For instance, for the partition 4+2+2+1+1 of 10, the prefix sums are 4, 4+2=6, 4+2+2=8, and 4+2+2+1=9, so we get ones in the 4th, 6th, 8th, and 9th bits of the vector: 000101011. Replacing a pair of values in the partition by their sum, or splitting a value into two smaller powers of two, corresponds to changing a single bit in these vectors, so graph distance is at least as large as Hamming distance. To find a graph path as short as the Hamming distance between two partitions, simply split the largest value that occurs more times in one partition than the other and continue finding a path between the resulting partition and the other one.

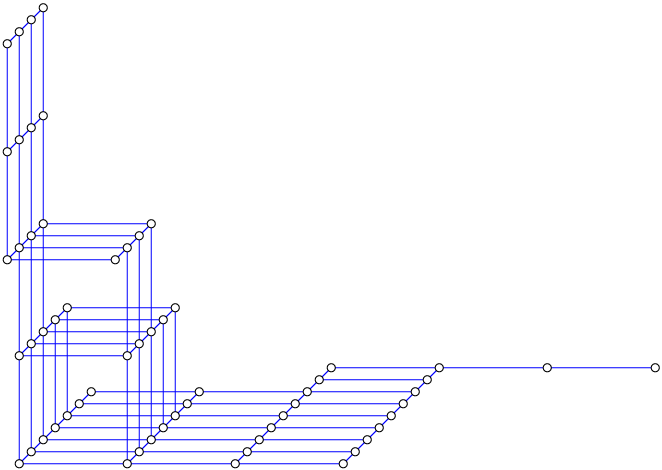

Due to this, we can apply all the algorithms for partial cube computations I've been working on, including the ones for drawing partial cubes nicely, to show the structure of the set of binary partitions. E.g., below are the binary partitions of 20; the coarsest partition 16+4 is at top left while the vertex at lower right represents the partition into 20 ones.

From this drawing, it appears (and one can verify) that this graph can actually be embedded in a distance-preserving way using three-dimensional integer coordinates (under the L1 metric), even though the bitvector representation uses 19 dimensions. The three-dimensional coordinates were found automatically by an algorithm for minimum-dimension lattice embedding. In general, for binary partitions of \( n \), at most \( \lfloor\log_2 n-1\rfloor \) integer coordinates are needed (the splits of the same size values form edges that can all be lined up along the same dimension) but this example hints that this is not a tight bound.

Unfortunately, the same prefix-sum labeling does not generally give a partial cube representation of unrestricted partitions: 4+3+3 and 4+4+2 have bitvectors at Hamming distance two, but require at least four merge and split operations to reach one from the other: 4+3+3 ⇒ 7+3 ⇒ 10 ⇒ 8+2 ⇒ 4+4+2 or 4+3+3 ⇒ 4+3+2+1 ⇒ 4+3+1+1+1 ⇒ 4+4+1+1 ⇒ 4+4+2. It may be more natural to allow merges and splits of values that need not be consecutive, but that would lead to graphs that are even less like partial cubes, e.g. the partitions 6, 5+1, 4+2, 3+3, and 3+2+1 of six would form a \( K_{2,3} \) subgraph, not possible in any partial cube.