Some pyramidology

Another Wikipedia editor, “Dedhert.Jr”, recently brought Wikipedia’s square pyramid article up to Good Article standards. In honor of their achievement, I thought it might be fun to analyze the proportions of various famous pyramids.

For the famous pyramids in Egypt, this sort of analysis has been both a hobbyhorse of fringe archaeologists and a difficult task, because we don’t have detailed original construction plans and because the removal of the outer surface of the pyramid for construction materials elsewhere has made it impossible to provide accurate physical measurements. We know the approximate dimensions, but not to an accuracy that would distinguish the different fringe theories. Instead, we have to choose among them based on our knowledge of Egyptian mathematics and proportion, which (according to more reputable scholars) both point towards simple integer ratios instead of mystic knowledge of irrational numbers. But for modern pyramidal buildings, we have more information and can determine more accurately their proportions. And for different forms of the mathematical square pyramid, we can of course calculate these things precisely.

The image below is a reproduction of Wulf Barsch’s The Template, stolen from the endpaper of an issue of Dialogue, a Mormon theological journal. Theology aside, Barry Laga argues within the journal (pp. 66–67) that this piece “celebrates form itself—the pleasure of straight lines, symmetry, systematic relationships, and cause-effect relations between conception and result”, and “invites us to reflect on the relationship between the authentic and the artificial, the scientific and the natural, human creations and natural creations, and the concept of convergence itself”. As I previously mentioned, I’ve had a poster of this painting hanging in my office for many years, and Laga articulates well what appeals to me about it.

There are several different ways to measure a pyramid; I’m going to consider mainly the height (from the center of the base to the apex) and width (along any of the edges of the square base). Another measurement that has historically been important is the “slant height”, the distance from a base edge midpoint to the apex. Any one of these is easily calculated from the other two using the Pythagorean theorem.

First, the mathematical pyramids:

-

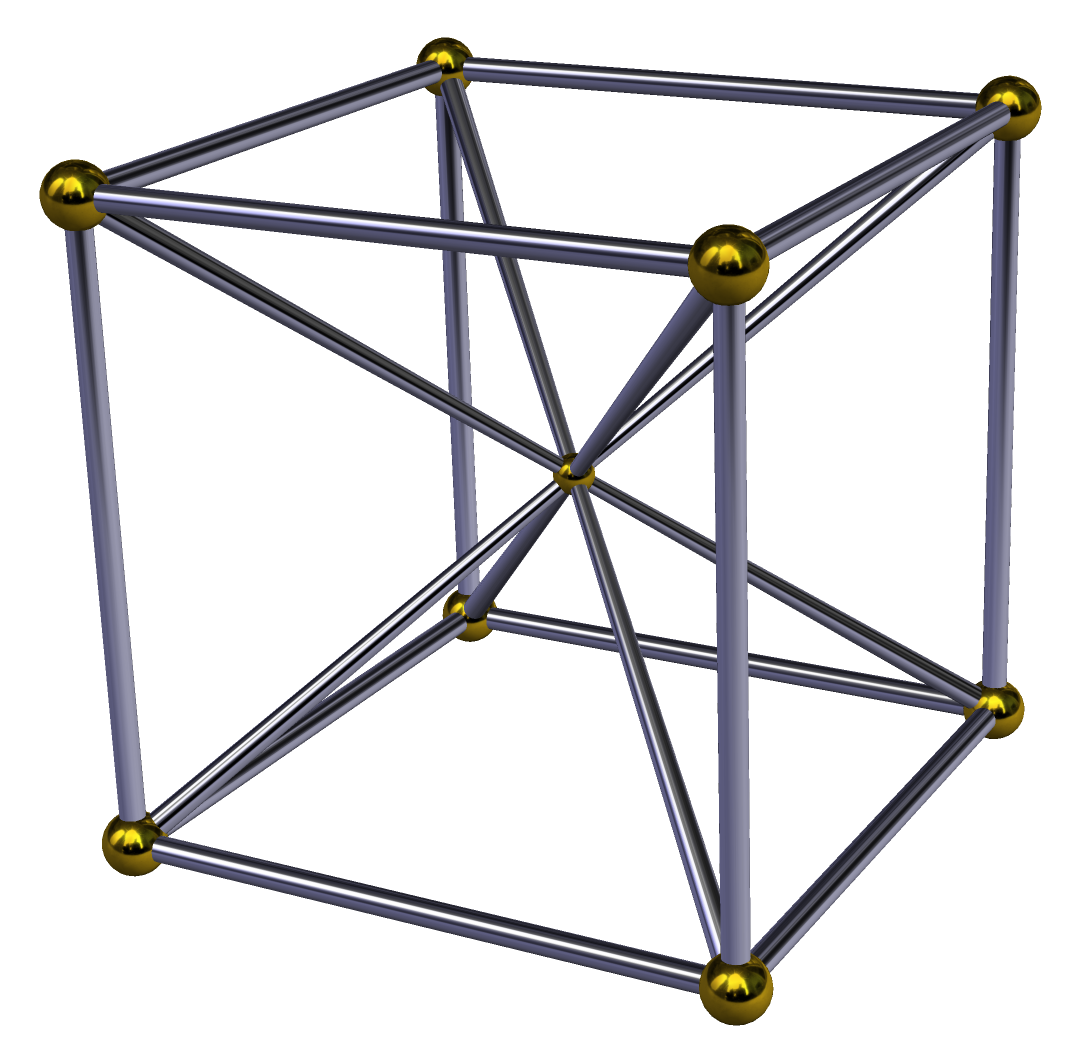

If you subdivide a cube into six pyramids based on its six square faces, with their common apex at the center of the cube, then the height to width ratio of each pyramid is exactly \(\tfrac12=0.5\).

-

A common fringe theory for the shape of the Great Pyramid of Giza, the so-called “golden pyramid”, is based on the golden ratio, with a doubled Kepler triangle (shown below) as the cross-section through a plane that bisects two opposite sides of its square base. The golden ratio \(\varphi=(1+\sqrt5)/2\) shows up as the ratio of the slant height to half the width. The height to width ratio is \(\tfrac12\sqrt{\varphi}\approx 0.6360\).

-

Another fringe theory uses \(\pi/2\) in place of the golden ratio for the slant height, giving height to width ratio \(\tfrac12\sqrt{\pi^2/4-1}\approx 0.6057\).

-

The semiregular square pyramid has equilateral triangle faces. This is also what you get if you slice a regular octahedron in half. Its height to width ratio is \(\tfrac12\sqrt2\approx 0.707\), noticeably pointier than the Great Pyramid.

-

The canonical polyhedron form of the square pyramid has the property that, if you twist it by \(45^\circ\) and flip it upside down, the result can be aligned with the original pyramid so that every edge of the original pyramid crosses perpendicularly to an edge of the twisted and flipped pyramid, with a single sphere tangent to all of these crossings. If I have calculated it correctly, its height to width ratio is

\[\sqrt{1+\sqrt{2}}\approx 1.554,\]extremely pointy. I’ve drawn a schematic view below in which you see the outline of one pyramid (blue) side-on, its dual flipped and twisted copy (red) edge-on, and the midsphere through their crossing points (yellow).

Now on to some real-world pyramids, the first two of which are mentioned in the newly promoted Wikipedia article (there are too many others to list them all there or here):

-

The Louvre Pyramid, a “glass-and-metal structure” by I. M. Pei in the courtyard of the Louvre in Paris, is reported in the linked Wikipedia article to be 34 meters wide and 21.6 meters tall, giving it a ratio of approximately 0.635, matching the golden pyramid to within the numerical precision given for its measurements.

-

The Luxor, a hotel in Las Vegas, is named after an Egyptian city. Unfortunately it seems difficult to track down its true dimensions. I can find lots of school assignments claiming that it is 646 feet (197 meters) wide and 350 feet (107 meters) tall, for a ratio of 0.542, well below the Egyptian pyramids). But a newspaper article from near the time of its construction gives the height instead as being 357 feet (109 meters), the dimension used by Wikipedia, without mentioning its width. If we imagine that the 646 width number is accurate, but take the height as 357 feet, the ratio would be 0.553, still well below the Egyptian pyramids and far from any of the other mathematical pyramids.

-

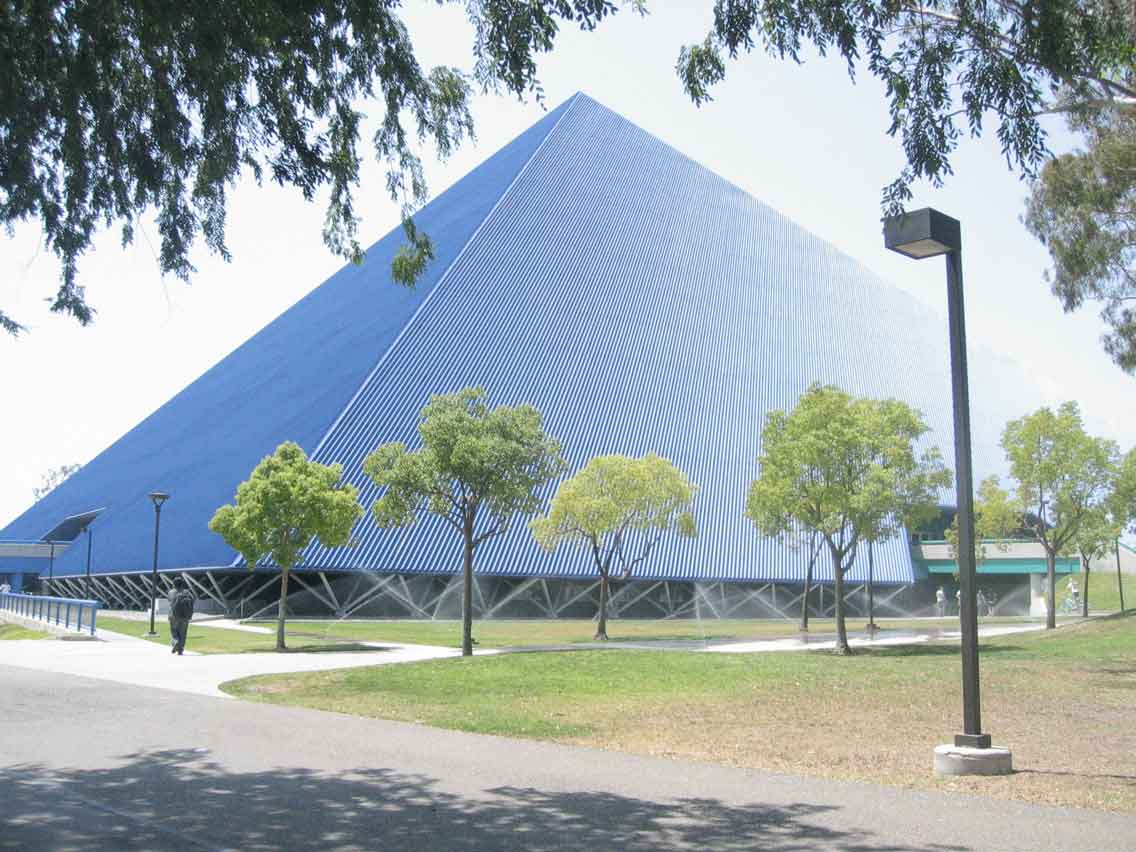

The Walter Pyramid is a sports arena at California State University, Long Beach, visible as a landmark to hundreds of thousands of daily Southern California commuters on the 405. Structurae gives its dimensions as 105.16 meters in width, 57.91 meters in height, for a ratio of 0.551, also nothing like any of the mathematical pyramids.

What about Barsch’s pyramids? Assuming they are viewed side-on, from an unlikely orthogonal perspective, they appear from their visible angles to have a height-to-width ratio of roughly 0.59, close enough to the Egyptian pyramids to be a plausible match for them but not really the same as the two fringe theories for the pyramids.