Flipping until you are lost

Start with any triangulation of a convex polygon, and then repeatedly choose a random diagonal and flip it, replacing the two triangles it borders with two different triangles. Eventually, these random flips will cause your triangulation to be nearly equally likely to be any of the possible triangulations of the polygon. But how long is “eventually”? My student Daniel Frishberg has a new answer, in our preprint “Improved mixing for the convex polygon triangulation flip walk” (arXiv:2207.09972).

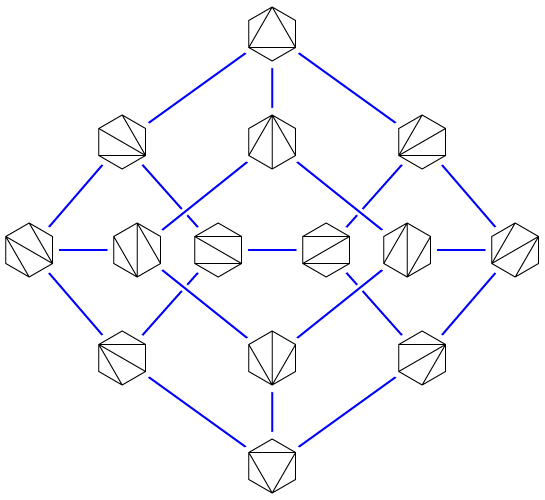

The triangulations of an \(n\)-gon, and the flips between them, form the vertices and edges of an \((n-3)\)-dimensional convex polytope called the associahedron; the example above, showing the flips of a hexagon, is from an older post. It’s difficult to convey all the symmetries of the four-dimensional associahedron (representing the triangulations of a heptagon) in a planar drawing, but here it is as a graph, at least:

The number of steps until a random walk converges to near its stable distribution is called its mixing time. So another way of stating the results in the preprint is that we provide a new bound on the mixing time of associahedra. A 1997 paper of McShine and Tetali shows that this mixing time is \(O(n^5\log n)\), and we improve the exponent slightly, to \(O(n^{4.75})\). Which doesn’t sound like much, but it’s the first improvement in 25 years!

It’s part of a line of research Daniel has been following on mixing times, treewidth, and expansion of large state spaces, including Hanoi graphs and independent sets in bounded-treewidth graphs. Like those other papers, it exploits known connections between mixing time, treewidth, expansion, and multi-commodity flow to formulate the problem as one of finding a system of paths between every pair of vertices in the associahedron in such a way that each edge of the associahedron is used only for a small fraction of these paths. The construction of these paths exploits a recursive decomposition of the associahedra into products of smaller associahedra, obtained by cutting out a central triangle of any triangulated polygon and using associahedra to describe the triangulations of the remaining pieces.

The same paper also includes a weaker bound on the triangulations of rectangular grids of points. The convex polygons have a Catalan number of triangulations, but for grids, we can’t say as precisely how many triangulations there are. Whatever this number \(N\) is, we show that these state spaces have treewidth \(N^{1-o(1)}\), by using a fixed choice of diagonals to partition the grid into smaller grids, triangulating each smaller grid independently, and showing that there are many of these partitioned triangulations and that their product structure gives them high expansion. But this result is still somewhat unsatisfactory because it doesn’t consider all triangulations and because the \(N^{o(1)}\) part of the bound is not polynomial in the grid size. Do triangulations of grids have polynomial mixing time?