Gilbert tessellations from a cellular automaton

A Gilbert tessellation is what you get from choosing a random set of points-with-slopes in the plane, growing line segments in both directions with the chosen slope from each chosen point, at constant speed, and stopping the growth when each line segment runs into something else. The slopes can be in uniformly random directions but one standard variant of the Gilbert tessellation uses only horizontal and vertical slopes.

My paper “Growth and decay in life-like cellular automata” observed that the Life-like cellular automaton rule B017/S1, when started with a sufficiently sparse random set of live cells, forms lines of replicators that look sort of like one of these axis-parallel Gilbert tessellations, as I discussed in a previous post on sparse Life.

But it’s a bit messy: you also get stable or oscillating blobs of live cells, and replicators can sometimes make large gaps big enough for something else to get across them, rather than forming the impenetrable barriers that the segments of a true Gilbert tessellation would do. So I wondered: how easy is it to get Gilbert tessellations with less mess, in a cellular automaton?

Very easy, if you’re willing to make an automaton that hardcodes into its rules the construction process of a Gilbert tessellation. For instance, make an automaton on an infinite square grid with three states, empty, horizontal, and vertical. Horizontal cells always stay horizontal, and vertical cells always stay vertical. Empty cells with exactly one non-empty neighbor that is either a horizontally-adjacent horizontal cell or a vertically-adjacent vertical cell take on the same state as that neighbor, and otherwise stay empty. Then any horizontal cells will grow into horizontal walls, and vertical cells will grow into vertical walls, at constant speed, until running into other non-empty cells, just as the Gilbert tessellation definition demands. If you start with a sparse random set of non-empty cells of both types, you should get a Gilbert tessellation, more or less by definition. But controlling horizontal versus vertical growth by different cell states rather than by the pattern of live cells seems kind of a cheat. It makes creating Gilbert tessellations the only thing this three-state automaton can do, rather than an emergent behavior of the automaton. And it isn’t even symmetric under 90-degree rotations (although it does have a symmetry that combines rotation with state-swapping). Is there an automaton with only two states, and natural symmetric rules that can do other things but that when seeded randomly generates non-messy Gilbert tessellations?

Yes! I don’t know of a Life-like rule that does this (Life without death does make nice impenetrable walls but with too much other stuff). But I think the rule below fits the bill. It’s the first thing I tried, at least, so I didn’t have to do any fine adjustments of the rules to make it work.

Here’s the rule:

-

The cells form a square grid with the Moore 8-cell neighborhood.

-

There are two states of cells, live and dead.

-

A dead cell becomes live only under two conditions:

-

It has exactly two live neighbors (among its eight possible neighbors) that are orthogonally adjacent to each other.

-

It has exactly four live neighbors at the corners of a rectangle (necessarily in two orthogonally adjacent pairs, because we don’t count squares as being rectangles).

-

-

All live cells immediately die.

Or, in Golly rule format:

@RULE Gilbert

@TABLE

n_states:2

neighborhood:Moore

symmetries:rotate8reflect

var a={0,1}

var b={0,1}

var c={0,1}

var d={0,1}

var e={0,1}

var f={0,1}

var g={0,1}

var h={0,1}

0,1,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,1

0,1,1,0,1,1,0,0,0,1

1,a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h,0

Then an initial pattern of two orthogonally adjacent live cells (a “domino”) will in the next step form two side-by-side dominos, in the step after that three dominos (with the center one in the initial location), and so on, building a wall two cells wide that alternates between dominos and dead cells, and oscillates with period two.

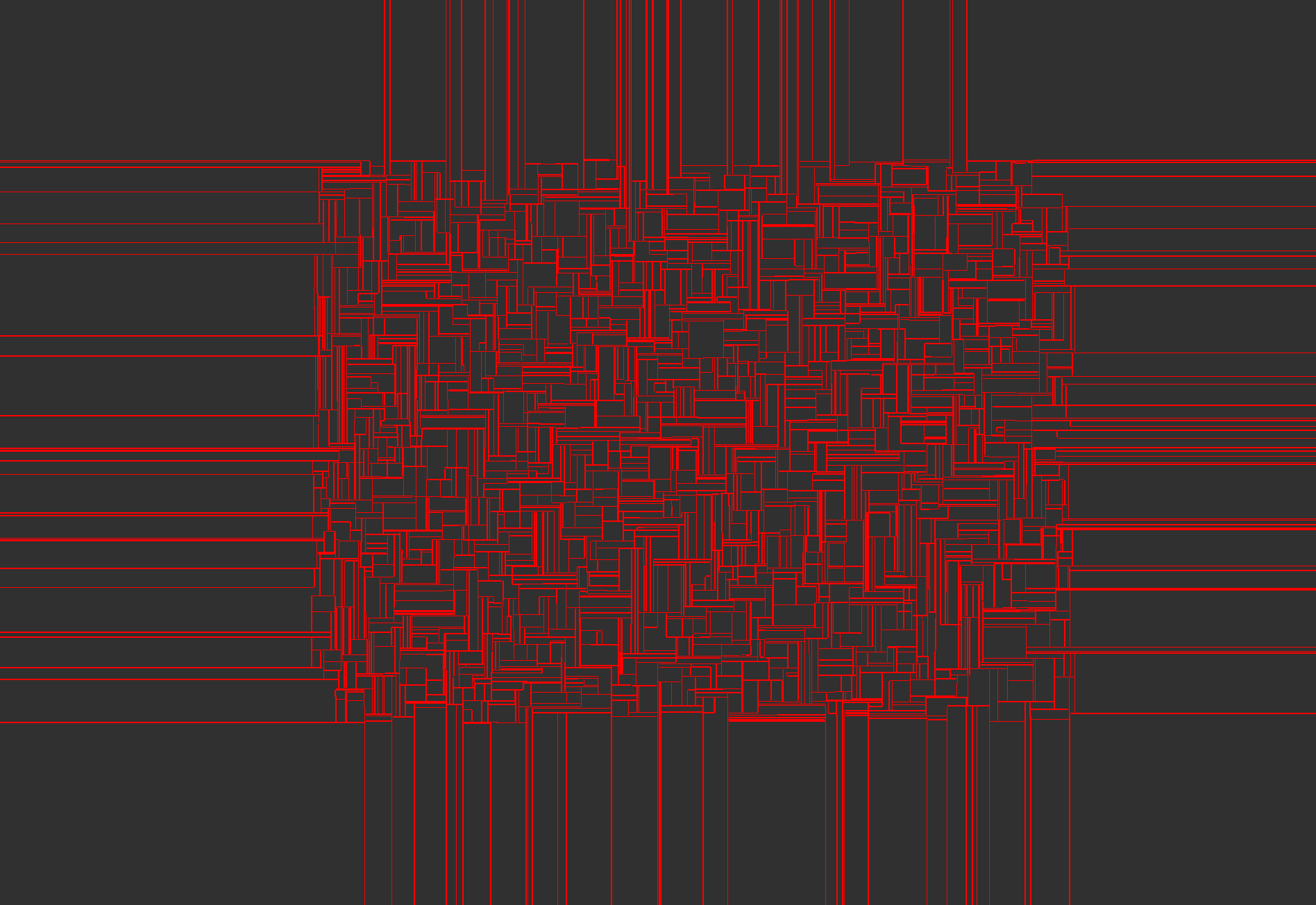

Here’s what it looks like when I selected a large rectangle, randomly filled it with 2% live cells, and ran it in Golly. The red lines in this image are walls like the one above.

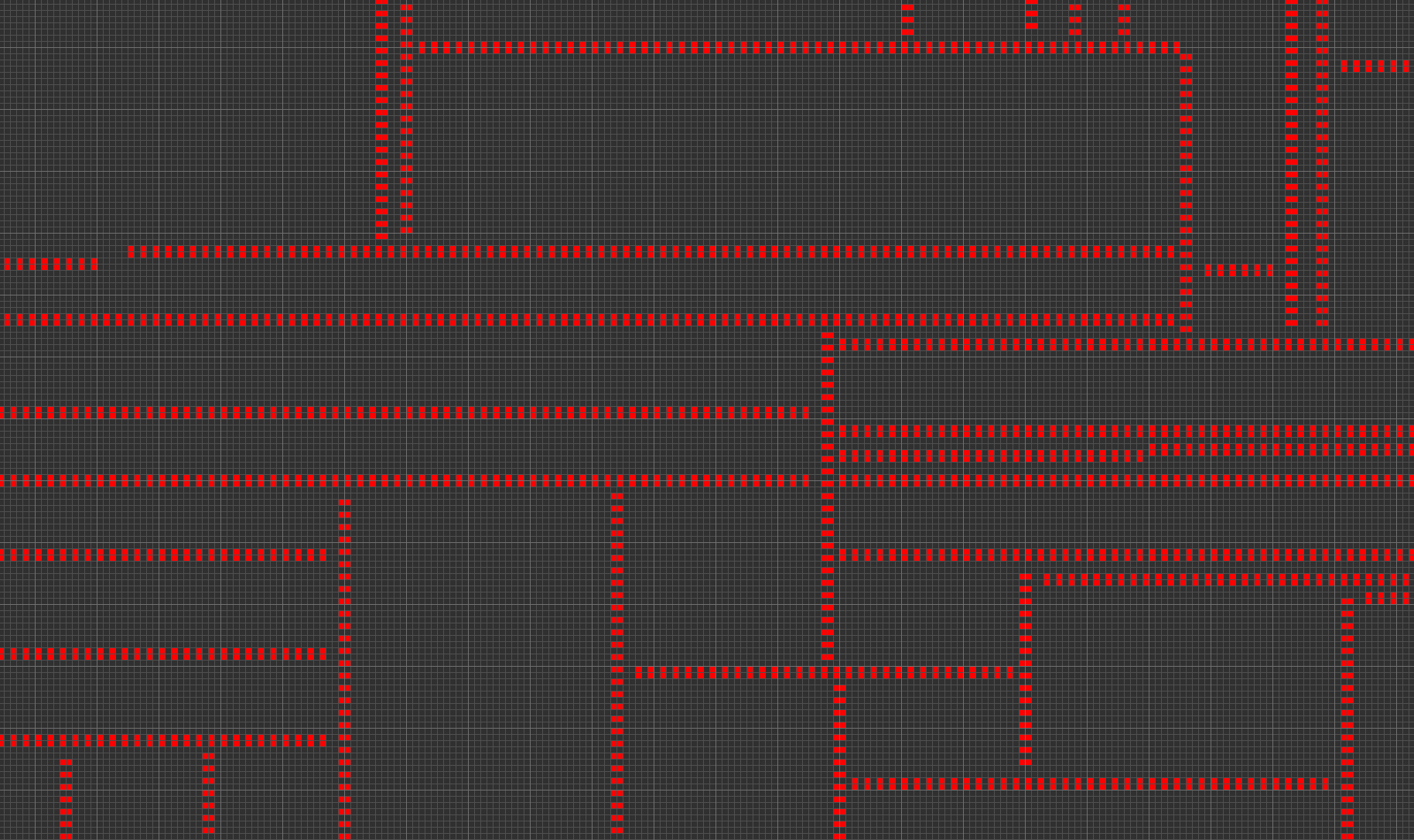

Of course, at the edges of the randomly filled rectangle, the walls shoot off to infinity with no more obstructions. Here’s a closeup, showing the detailed pattern of the walls and how they meet:

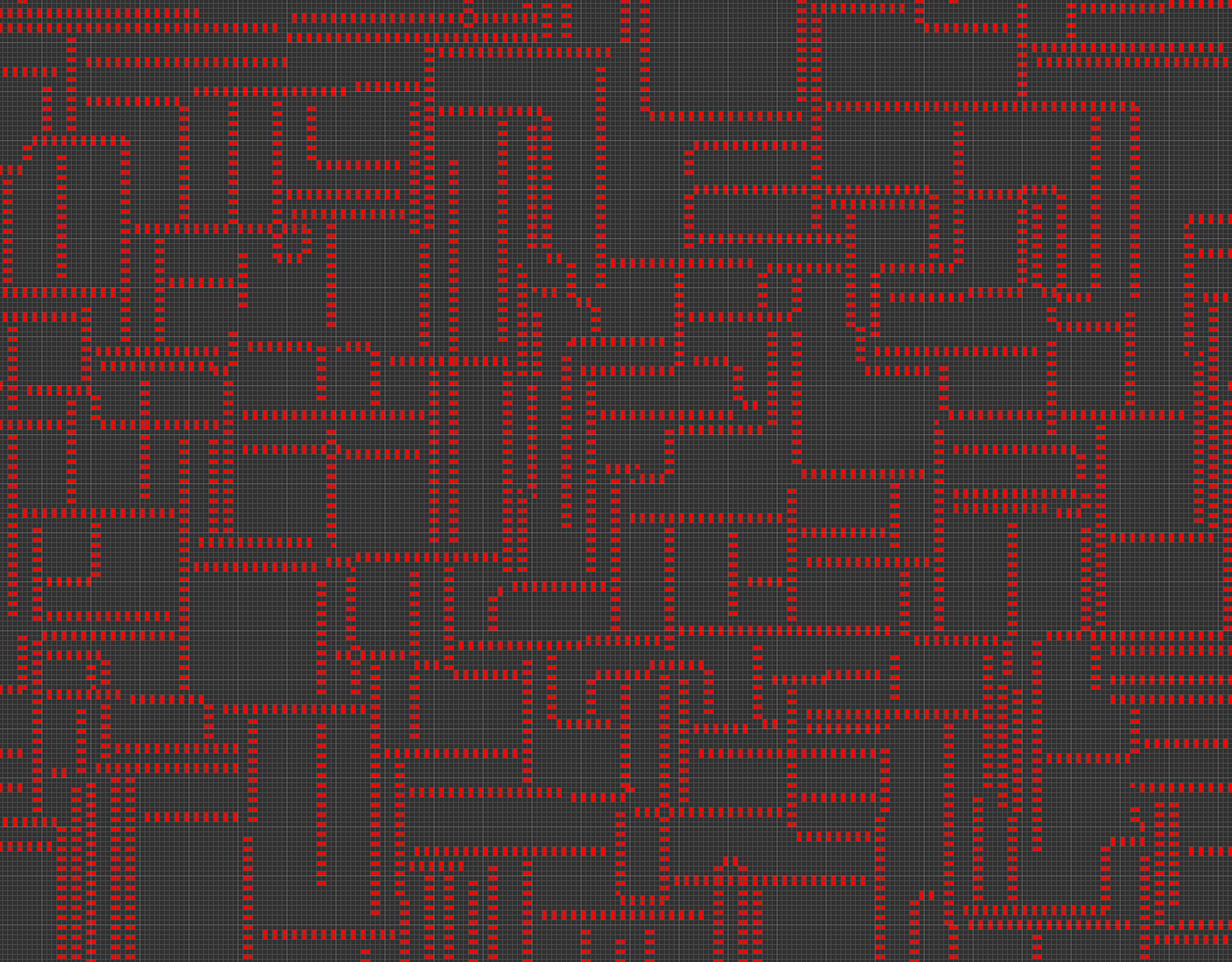

It looks a lot like a Gilbert tessellation to me! Even starting with a 50% random fill produces the same sort of pattern at a finer scale:

But rather than just going by intuitive visual appearance here’s some analysis showing that, if the plane is filled with live cells with some small probability \(p\), and then this rule is run on the result, then as \(p\to0\) the probability of seeing something that looks like a Gilbert tessellation in the neighborhood of any cell will tend to one. By “neighborhood” I mean everything within distance \(r\), where \(r\) should be chosen as a function of \(p\) that grows faster than linearly in \(1/p\) (so that we have nontrivial probability of seeing something other than just empty space) but slower than \((1/p)^{4/3}\).

The reason we need to limit the radius of the neighborhoods is that, in a large enough neighborhood, you will likely see something that deviates from a Gilbert tessellation. In the runs above, for instance, there are some right-angle corners where two line segments both meet and stop, or points where it appears that walls met head-to-head, but this shouldn’t happen in a Gilbert tessellation (or more precisely it happens with probability zero). There are two natural ways of getting a corner: you could start with an L-tromino of live cells, or two growing walls could coincidentally run into each other. But the expected number of triples of nearby live cells within the neighborhood is \(O(p^3r^2)\), and the expected number of pairs of dominos whose walls would meet at the same point is \(O(p^4r^3)\). It might also be the case that three or more initial live cells produce more exotic behavior; if so, the expected number of things like this that happen within the neighborhood is still \(O(p^3r^2)\). With our assumption on the growth rate of \(r\) relative to \(p\), these expected numbers, and therefore the probability of seeing any of these situations within the neighborhood, is negligible. For the same reason they have low probability of occurring close enough to the neighborhood to impinge on it before the Gilbert tessellation within the neighborhood forms.

So with high probability, in neighborhoods of radius \(r\), you’ll only see single live cells and double live cells in the initial state, and the pairs of double cells won’t be horizontally, vertically, or diagonally aligned with each other. Some of the double live cells will be dominos, with density \(\Theta(p^2)\). The only thing that can happen with such a state is that dominos start building walls which grow until they hit each other, exactly as described by a Gilbert tessellation. Once the Gilbert tessellation has been set up, it appears indestructible: the alternating live cells along the wall prevent any births into the layers of dead cells on either side, and if a wall is perturbed at its end it quickly grows back. However, proving this indestructability rigorously would require a more careful case analysis.