Predicting weighted ranks

This week’s events have included Olympic sport climbing, for the first time. The NBC livestream of the women’s qualification suffered a bit of an embarrassment, though, as the computer display of the results incorrectly showed some competitors as being guaranteed to qualify when they were not. (Rest of post contains spoilers; don’t click if you don’t want to know about the outcomes of the event.)

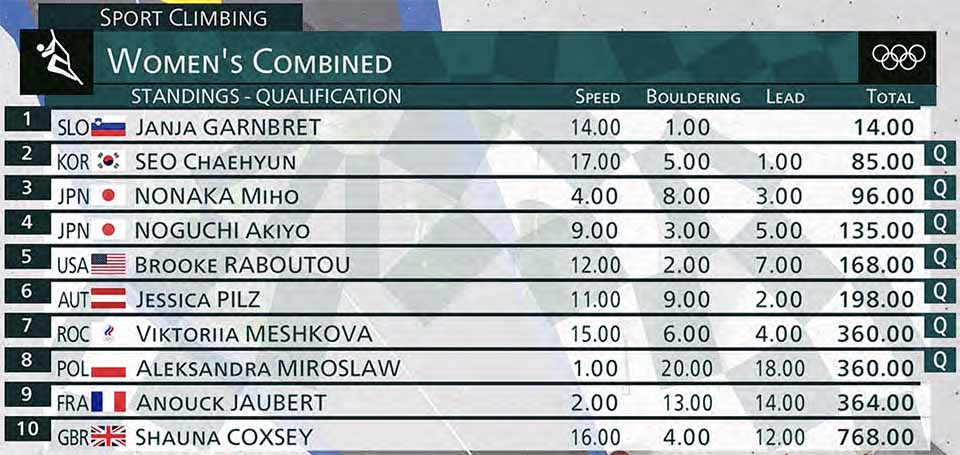

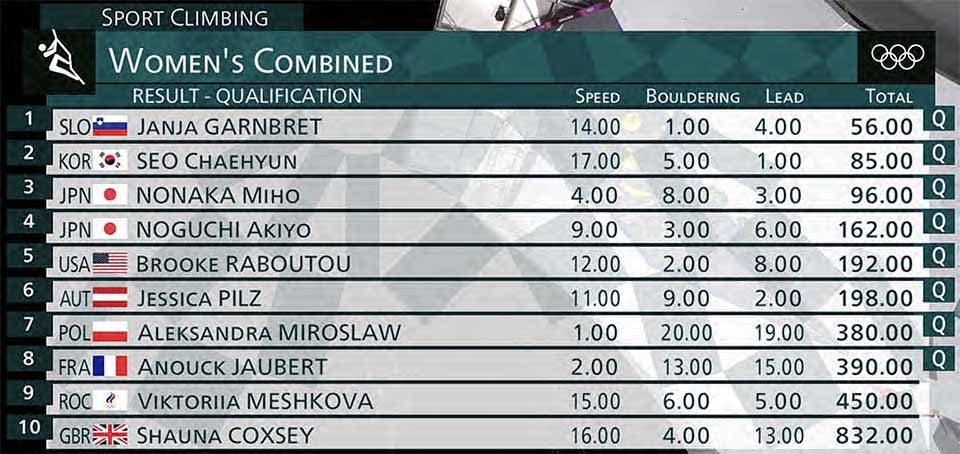

For example, the screenshot below shows Viktoriia Meshkova as a qualifier, with Janja Garnbret still to climb, but Meshkova was actually eliminated after Garnbret’s climb. The commentators noticed the problem and had to tell the audience not to pay attention to that part of the display. What went wrong, and how could it have been done correctly?

Background

The important things to know about this event are:

-

It involves three disciplines, speed, bouldering, and lead, in that order. One discipline finishes before the next one starts (in fact there is a long rest period between each two disciplines).

-

The scores from each discipline are turned into orderings, giving each of the competitors a number from 1 to 20, before combining them into a single outcome. Each of 20 competitors gets a rank from 1 to 20 in each of the three disciplines.

-

These numbers are multiplied and the eight competitors with the smallest product of ranks advance to the final round.

-

In lead climbing, the ranks are based on how high each competitor climbs, with ties broken by time, so any competitor who has not yet climbed can slot into the ranking in any position.

In screens like the one shown above, the livestream showed the standings of the competitor, ordered by their product of ranks: the product of two ranks for competitors who had not yet climbed and the product of all three current ranks for competitors who had already climbed. It predicted qualification for competitors who had already climbed and were in the top eight in this ordering. This seems reasonable, at first glance: the ordering among the people who have already climbed is set, and the people who have not yet climbed can only go down in the ordering, so they will stay in the top eight.

But the ordering among competitors who had already climbed is not set. In the example shown above, before Janja Garnbret climbed, Meshkova was ahead of two other climbers, Aleksandra Mirosław and Anouck Jaubert, both of whom had done well in speed and badly in lead. Garnbret climbed better than Meshkova, bumping Meshkova’s lead ranking down from fourth to fifth. That hurt Meshkova’s combined score a lot more than it hurt Mirosław’s and Jaubert’s, because Mirosław and Jaubert already had very high ranks in lead. At the end of the competition, Meshkova was behind Mirosław and Jaubert, and out of the competition.

Analysis

We can formulate this as an algorithms problem: Suppose we have \(n\) competitors, numbered \(1\dots n\), each with a weight \(w_i\) (their combined score from the previous disciplines). We have selected an ordering on a set \(X\) of the competitors, while the remaining set \(Y\) have yet to be ordered. The eventual ordering on \(X\cup Y\) must be consistent with the ordering we already know on \(X\). If competitor \(i\) ends up in position \(p_i\), they get a combined score \(w_i\cdot p_i\) and a combined rank based on sorting these combined scores. (To keep the terminology from being confused, I’ll stick to “ordering” for the result of a single discipline, and “ranking” for the combined result of the whole competition.) What we want to know, for each competitor number \(i\), is: what is the maximum possible combined rank \(r_i\)? Before formulating an algorithm for this problem, let’s do some analysis to find simplifying assumptions that can make the algorithm fast.

For the climbing competition, \(n=20\) and we only care whether \(r_i\le 8\) or \(r_i>8\): is competitor \(i\) guaranteed a spot in the final or not? More generally, we can ask the same question for any \(n\) and any threshold on the combined rank. We can also ask this question regardless of whether competitor \(i\) has already competed (that is, whether \(i\in X\)): if not, it’s safe to assume that they will end up last in the ordering, because that’s the slot that will give them the maximum combined rank.

For each competitor \(j\) in the set \(Y\) of not-yet-ordered competitors, it’s always safe to assume that \(j\) will slot in somewhere above \(i\) in the final ordering. Slotting in immediately above \(i\) is always worse for \(i\) than slotting in anywhere below \(i\), because it hurts the ranking for \(i\) more than it hurts anyone else. Therefore, it can only cause \(i\) to go down among the combined rankings of competitors who are already ordered. Once we make this assumption, we know the final position \(p_i\) of competitor \(i\) in our ordering, and therefore we also know the final combined score \(w_i\cdot p_i\). This assumption lets us determine which final scores beat \(i\), and (because the orderings are also fixed by this assumption) determines which of the competitors ordered later than \(i\) in \(X\) end up beating \(i\). What remains to be determined is which of the competitors ordered earlier than \(i\) in \(X\) might beat \(i\), and which of the competitors in \(Y\) might beat \(i\).

We don’t know how many competitors in \(Y\) beat \(i\), but we can guess; there are only \(\vert Y\vert\lt n\) possibilities to try. Suppose that we guess that this number is \(k\). If our guess is correct, then we can safely assume that these \(k\) better competitors are the ones in \(Y\) with the \(k\) smallest weights. Any other outcome that puts \(k\) competitors in \(Y\) ahead of \(i\) can be swapped to an outcome that puts these \(k\) competitors ahead, without changing the ranks of any competitors in \(X\).

Once we know which \(k\) competitors in \(Y\) beat \(i\), we also know how good a position \(p_j\) each of these competitors will need to attain, to beat \(i\). We can assign these competitors to these positions, breaking ties by moving some up into higher positions, determining where they all slot into the overall ordering. Among all assignments of positions to these competitors that puts them ahead of \(i\), this is the one that hurts the other competitors of \(i\) the least. Once this is done, we can safely assign all of the remaining competitors in \(Y\) to an ordering that slots them in just ahead of \(i\), again hurting \(i\) while causing the least hurt to the competitors of \(i\).

With the ordering of competitors completely determined by the choice of \(k\), all we need to do is try all choices of \(k\) and test which ones put the largest number of competitors ahead of \(i\)!

There is a complication here with tiebreaks that I am not handling. If two competitors get the same combined score, the one who is ahead in two of the three disciplines gets the higher combined rank. If three competitors get the same combined score, and they have a cyclic ordering on tiebreaks, I don’t know what happens, and I suspect the rules don’t cover that situation. To simplify things I will just assume that all tiebreaks go against the candidate (so we might not guarantee qualification until the ties are resolved).

Algorithm

Based on these simplifications, our algorithm for computing the maximum combined rank \(r_i\) of competitor \(i\) performs the following steps:

-

If \(i\) is not already in \(X\), add it to \(X\) with a position after all of the other competitors in \(X\).

-

Loop through all choices of \(k\) in \(0\dots\vert Y\vert\). For each choice:

-

Determine, for each \(j\) in the \(k\) smallest-weight competitors in \(Y\), the position \(p_j\) that \(j\) would need to obtain to beat \(i\)

-

While any two of these competitors have the same value for \(p_j\), decrement one of these two values. If this causes any value to become non-positive, continue the outer loop with the next choice of \(k\).

-

Place the competitors in \(Y\) that are not among the \(k\) smallest immediately above \(i\) in the ordering

-

Place the \(k\) smallest-weight competitors into positions \(p_j\), preserving the ordering of the remaining competitors.

-

In the resulting ordering, determine how many competitors beat \(i\)

-

-

Return the maximum number of competitors beating \(i\) in all of the orderings that have been examined

With some care it should be possible to do all of this in time \(O(nk)\). My implementation is slower because I was more interested in getting it to work than in optimizing it, and for \(n=20\) it is blazingly fast regardless.

Outcomes

With all that in mind, and assuming that (somehow) I’ve implemented this correctly, let’s look at what this algorithm predicts for the actual data.

At this stage of the qualifications, five competitors are left to climb. NBC predicted that Seo, Raboutou, and Pilz had already qualified, and my implementation agrees for Seo and Raboutou (both can finish at worst 8th) but it was incorrect for Pilz, who could drop to 9th if Mirosław miraculously finished 2nd and Garnbret 3rd. More surprising to me, Garnbret was still not an automatic qualifier: if she finished 20th, enough other competitors could better her score to put her into 9th place.

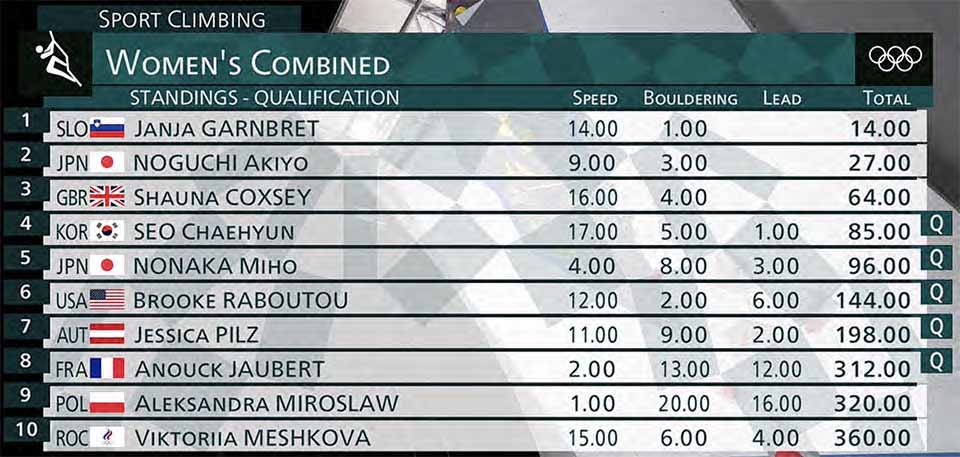

After two more climbs, the faulty NBC algorithm claims that five climbers have qualified. My program agrees for Seo (worst rank 6), Nonaka (worst rank 5), Raboutou (worst rank 7), but still not Pilz (worst rank 9) or Jaubert (worst rank 10). My code now thinks Garnbret has locked in a rank of at worst 7th, qualifying without even climbing yet.

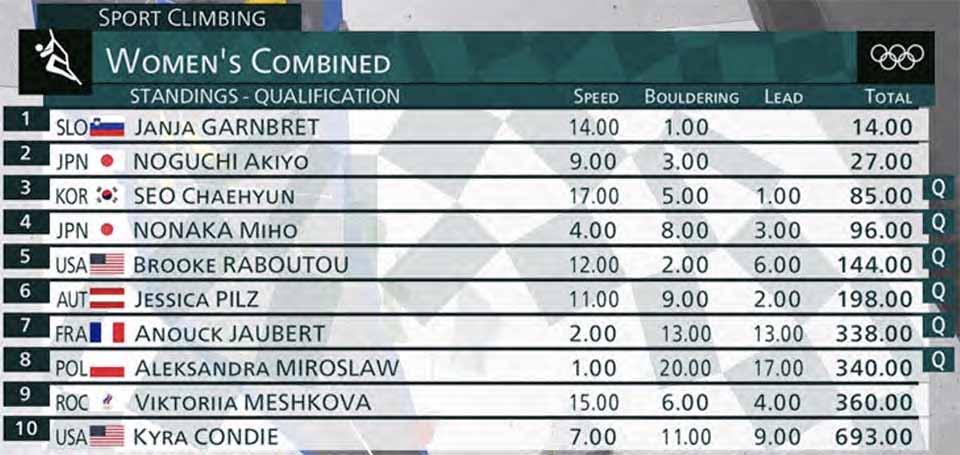

Shauna Coxsey, climbing with an injured knee, has climbed into the middle of the pack, falling off the top ten ranking, and her place has been taken by Kyra Condie. Garnbret is now at worst 6th and should have been marked as qualified. Noguchi is not quite guaranteed yet, with a scenario in which she could rank 9th. Seo is now at worst 5th, Nonaka at worst 4th, Raboutou at worst 5th, and Pilz at worst 8th (now guaranteeing her spot). But Jaubert and Mirosław each could end 9th; at most one of Jaubert, Mirosław, or Noguchi will be eliminated, but we can’t yet guarantee any of their spots.

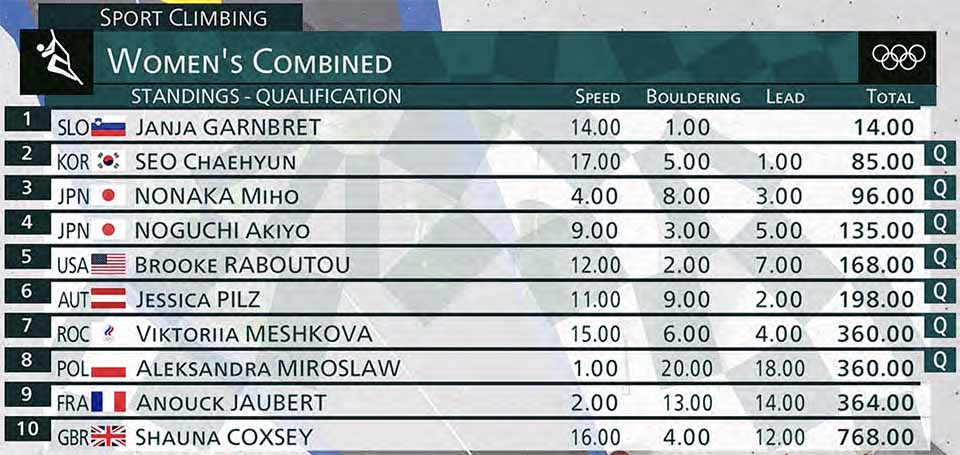

Until now, all of the “Q” markings shown on the livestream, while mathematically incorrect in many cases, were at least correct in hindsight: the people marked that way did end up qualifying. This one, though, a repeat of the first image in this post, gets it wrong in practice as well as in theory. Meshkova is marked as qualifying, but did not. Coxsey has moved back into the top ten. Mirosław and Jaubert could still have ended up 9th (under different scenarios, obviously) and should not have been marked as qualifying. Seo is at worst 4th, Nonaka is at most 3rd, Noguch is at most 4th, Raboutou is at most 5th, and Pilz is at most 6th.

And the final ranking:

The future

I think the moral of the story is that this ranking system is too hard to understand and a little too random (with players trading places too much depending on what other players do). To some extent this is unavoidable (a version of Arrow’s impossibility theorem for rank aggregation), but the scuttlebutt seems to be that this system will be replaced for future competitions. Which, sadly, makes all of this algorithm design a little redundant…