Carrying as chip-firing for the Zeckendorf representation

You may have heard of the Zeckendorf representation according to which any positive integer can be represented as a sum of non-consecutive Fibonacci numbers. Its uses include the optimal strategy in the game of Fibonacci nim. But did you know that it’s possible to efficiently add and subtract Zeckendorf representations?1 The algorithm from the paper linked above takes three passes over the input digit sequences using finite state automata, much like binary number addition can be performed by a single pass of a finite state automaton. I thought it might be interesting to describe an alternative path to the same result, using chip-firing games.

The chip-firing antimatroid

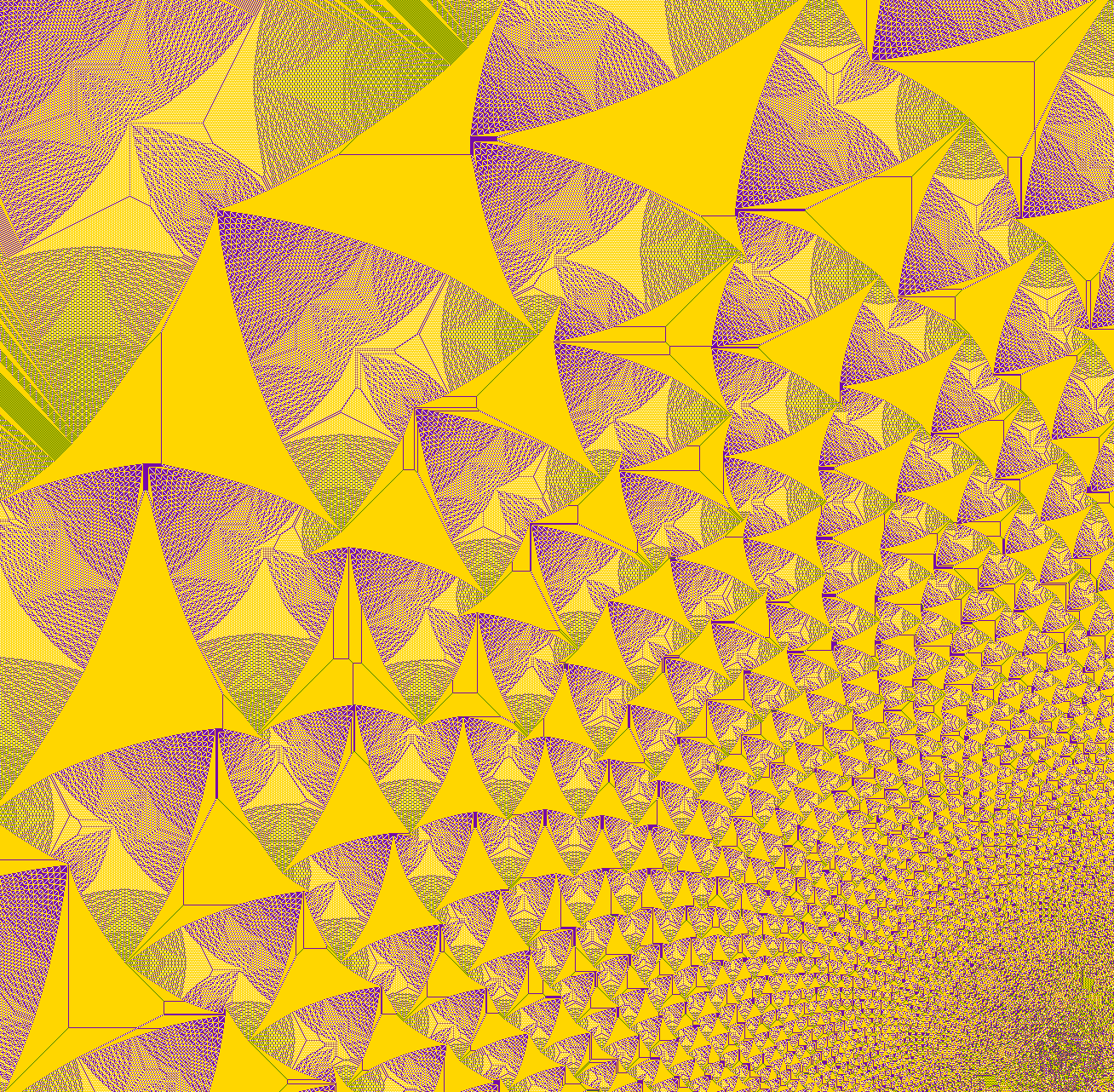

Chip-firing games, or sandpile models, are systems described by a graph, with markers of some kind such as coins on its vertices. The graph may possibly be directed, although in the simplest examples it is undirected, and it may be infinite. Each vertex may have arbitrarily many coins on it. But, if a vertex has at least as many coins as it has outgoing edges, we can “fire” the vertex, moving one coin to each neighbor. This repeats until no more such events are possible. Doing this on an infinite square grid with an initial state that piles many coins on a single vertex leads to pretty fractals; here’s a detail of the result of starting with 30 million coins:

However, we’ll be looking at this sort of system on one-dimensional infinite graphs, where their behavior is not quite as complicated.

Chip-firing, on any graph and any placement of coins for which it terminates, forms an antimatroid.2 3 A vertex \(v\) can fire for the \(i\)th time, as long as it has already fired \(i-1\) times and a total of \(i\cdot\deg(v)\) coins have reached it. Once these conditions are met, they remain true until \(v\) fires. This idea, that once the item \((v,i)\) becomes available to be added to the sequence of firings it remains available until it is added, is the defining principle of an antimatroid. From it one can prove that, if any firing sequence terminates in a stable configuration, then all sequences terminate, they all fire the same vertices the same numbers of times, and they all end in the same stable configuration.

Binary carrying as chip-firing

A binary representation of a number \(x\) is just a set of distinct powers of two, summing to \(x\). If you add two binary numbers \(x\) and \(y\), you can combine their sets into a single multiset; carrying can be thought of as a systematic method of getting rid of the duplicate powers of two in this multiset. Whenever you have two equal powers of two in a multiset, whose sum you are trying to represent, you can merge them with the fusion rule

\[2^i+2^i \Rightarrow 2^{i+1}.\]This can be thought of as a chip-firing game on a graph where there is a vertex for every power of two, an edge to the next larger power of two, and an edge to a “bit bucket” vertex with no outgoing edges (which cannot be fired). Each instantiation of the fusion rule fires vertex \(2^i\), moving one coin to \(2^{i+1}\) and one to the bit bucket.

This is exactly what we are doing when we carry a term in binary addition: taking two powers of two from a column of the addition problem and fusing them into a single power of two in the next column. We can also think of this physically, using a one-dimensional array of cells with poker chips or coins on them, with a coin on cell \(i\) representing the number \(2^i\). The fusion rule takes two coins from any cell and replaces them by a single coin in the next cell. In binary addition of pairs of numbers, there are at most three coins per cell (the two that started out there and one carry), but you could use the same fusion rule for addition of more than two numbers, using an array of cells that can each contain a large pile of coins.

Carrying the coin analogy further, we might imagine that the coins have values that are powers of two, and that we are making change by replacing pairs of small coins by a single larger coin of equal value.

Conventional binary arithmetic does these fusion steps in a systematic order, from low-order bits of the binary representation (smaller powers of two) to higher-order bits (larger powers of two). It’s that systematic order, together with the observation that each pile has at most three coins, that makes this method suitable for a finite state machine. But actually, you could apply the fusion rule in any order, and it would work equally well. Each step reduces the number of coins by one, so you can never do more steps than your starting number of coins. We can only halt when we reach the binary representation of the sum, which is uniquely determined, so this process is confluent: every sequence of choices leads to the same eventual outcome. In this case, confluence can also be seen from the antimatroid property of chip-firing games.

This observation about reducing the number of powers of two gives an immediate proof of a fact about binary representations that you may not have known: the binary representation of \(x+y\) has at most as many nonzero bits as there are in \(x\) and \(y\) separately.

Chip-firing for Fibonacci numbers

Now, instead of coins with power-of-two values, let’s suppose that they have Fibonacci numbers as their values, representing any multiset of Fibonacci numbers. We can still combine pairs of Fibonacci numbers by a fusion rule, that now applies when we have two coins in adjacent piles:

\[F_i + F_{i+1} \Rightarrow F_{i+2}.\]But in order to get the Zeckendorf representation of the sum of the multiset, we also need to deal with pairs of coins that have the same value, because repeated copies of the same Fibonacci number are not allowed in the Zeckendorf representation. We can accomplish this by a “fission” rule, that steps backwards according to the fusion rule in order to take a bigger step forwards:

\[F_i+F_i \Rightarrow F_{i-2}+F_{i-1}+F_i\Rightarrow F_{i-2}+F_{i+1}.\]This makes sense even when \(F_i\) is \(1\) or \(2\): for \(F_i=1\), the \(F_{i-2}\) term is zero and can be dropped from the sum, and for \(F_i=2\) it equals one, a Fibonacci number. So as special cases of this rule we have \(1+1\Rightarrow 2\) and \(2+2\Rightarrow 1+3\).

Several issues complicate the analysis of this replacement system. First, although fission by itself is a chip-firing rule on an infinite graph with outdegree two, fission and fusion together make a more complicated system that is not an antimatroid, so different orderings of choosing what to do may lead to different numbers of steps. Second, the fission rule changes the piles of coins both to the left and to the right of the pile to which it applies, making it harder to find a consistent ordering in which to apply these rules. And third, fission preserves the number of coins rather than reducing them, making both the eventual termination of the system and the analysis of how many steps it takes less obvious. But assuming it does terminate, it can only terminate at the Zeckendorf representation, which is unique. So termination implies confluence.

Fission without fusion

First let’s see what happens if we just use the fission rule, forgetting about the fusion rule. Because fission by itself is a chip-firing rule, any initial state has an invariant number of firings and an invariant final state, regardless of the order of operations. For an initial state with \(n\) copies of \(F_i\), the final state gives us an expansion of \(F_i\) into a sum of \(n\) distinct Fibonacci numbers:

\[F_i = F_i\] \[2\,F_i = F_{i-2}+F_{i+1}\] \[3\,F_i=F_{i-2}+F_i+F_{i+1}\] \[4\,F_i=F_{i-4}+F_{i-3}+F_i+F_{i+2}\] \[\vdots\]The indexes appearing in these identities can be summarized in a triangle of numbers:

\[\begin{array}{ccccccc} &&&&&&0&&&&&&\\ &&&&&-2&&\ 1\ &&&&&\\ &&&&-2&&0&&\ 1\ &&&&\\ &&&-4&&-3&&0&&\ 2\ &&&\\ &&-4&&-3&&-2&&1&&\ 2\ &&\\ &-4&&-3&&-2&&0&&1&&\ 2\ &\\ -6&&-5&&-4&&-3&&-1&&1&&\ 3\ \\ &&&&&&\vdots&&&&&&\\ \end{array}\]The largest number in each row grows only logarithmically with \(n\), because of the way the values of the Fibonacci numbers grow exponentially as a function of their index. The fission rule cannot create gaps of three or more empty cells, so consecutive numbers in a row differ by at most three, implying that the smallest number in each row is greater than \(-3n\). Because of this linear bound on how far fission can move the coins, we get a quadratic bound on the total number of firing events: each firing decreases the total distance of the coins from cell \(-3n\). This total distance starts at \(3n^2\) and remains positive, so there can be at most \(3n^2\) firings. In computational experiments up to \(n=10000\) the actual number of firings never exceeded \(n^2\) and appeared to be growing as \(n^2\bigl(1-o(1)\bigr)\). This is a big contrast from the behavior of the similar-looking chip-firing rule on a line of cells that replaces pairs of coins by a coin one cell to the left and a coin one cell to the right, which (with \(n\) chips starting in a pile on one cell) produces a square pyramidal number of firings, cubic in \(n\).

For initial coins that are not all in one big pile, it remains impossible for fission to produce new long gaps, and we can decompose the sequence of cells into subsequences of linear length separated by gaps too long to be crossed. The same analysis of total distance of coins from the starts of sequences of cells shows that, regardless of starting state, and even if we also allow fusion rules, we get an \(O(n^2)\) bound on the total number of steps. In particular, this system always terminates.

Taking few steps

Fortunately, we don’t have to take quadratic time to simplify sums of Fibonacci numbers into their Zeckendorf representations using these rules. The problem with the previous analysis was that we were doing too much fission before we did any fusion. Suppose we sidestep that with the following prioritization:

- If any fusion step would put a coin into a pile that is currently empty, do it.

- Otherwise, perform a fission step at the pile with the largest possible index.

If any fusion steps are possible, there must be at least one (for instance, the one with the largest index) that is prioritized. To analyze these prioritized steps, define \(N\) to be the current number of coins, and \(M\) to be the number of coins that are at or below a pile with two or more coins on it. The key insight is that whenever a step moves a coin to a pile with a larger index, it cannot form a new larger-index multi-coin pile, so both \(M\) and \(N\) are non-decreasing. They can stay the same only for a fission step at a pile of three or more coins, but in that case the next step must be a fusion. \(M\) and \(N\) are both \(\le n\), and their sum decreases at least once for every two steps, so the total number of steps is \(\le 4n\). Thus, this prioritized chip-firing method can reduce any sum of Fibonacci numbers to its Zeckendorf representation in a linear number of steps. It’s also not difficult to implement so that it takes linear time.

Zeckendorf arithmetic

Anyway, now that we have a way of simplifying sums of Fibonacci numbers to their Zeckendorf form, let’s use it for arithmetic on Zeckendorf representations, without the need to reduce them to simpler forms.

First, addition. This is very easy: Add the two Zeckendorf representations as multisets (producing piles of coins that might be adjacent, or might have two coins in them) and then simplify. The result is a linear time for adding two Zeckendorf representations, as was already known. But because it isn’t based on finite state machines, it can also handle more than two coins, for instance by adding multiple numbers at once rather than having to reduce the problem to multiple pairwise additions. As with binary arithmetic, the chip-firing method gives a quick proof of a non-obvious fact: the Zeckendorf representation of \(x+y\) has at most as many nonzero terms as there are in \(x\) and \(y\) put together.

It’s also possible to use this technique (or really, any linear-time Zeckendorf addition algorithm) as part of a long multiplication algorithm for Zeckendorf representations. To multiply two numbers \(x\) and \(y\), both given by their Zeckendorf representations, first perform a sequence of additions to compute the representations of the numbers \(F_i\cdot x\), each computed as \((F_{i-1}\cdot x)+(F_{i-2}\cdot x)\) in a single addition from earlier numbers in the sequence. Then pick out the subset of these representations for which \(F_i\) belongs to the Zeckendorf representation of \(y\), and add them together. (Or interleave the computation of \(F_i\cdot x\) and the sum of these representations, to save space.) The total time for \(\ell\)-bit inputs is \(O(\ell^2)\), as it is for the usual long multiplication algorithm. I’m using the different variable \(\ell\), because the time here is a function of all the bits in the input Zeckendorf representation, rather than just the number of nonzero bits.

You can convert a binary number to Zeckendorf with the same idea, computing the sequence of powers of two and then picking out and adding together the subset of these powers used in the binary representation of the input. In the other direction, you can convert a Zeckendorf representation to binary by computing the Fibonacci sequence in binary, picking out the terms from the given Zeckendorf representation, and adding them. Both directions of conversion take time \(O(\ell^2)\). A recent paper by Sergeev shows how to do these conversions much more efficient, only logarithmically slower than binary-number multiplication.4 Based on Sergeev’s results it would also be much more efficient (in theory at least, if not necessarily in practice) to multiply Zeckendorf representations by converting to binary, multiplying in binary, and converting back.

As the article I linked at the start hints, the direct algorithms described here are a bit unsatisfactory from the point of view of circuit complexity: the circuit size is ok but the circuit depth is much larger than it would be for binary arithmetic. I’m not convinced that this is a serious deficiency, because we’re not likely to build computers that use this arithmetic at the circuit level. Any algorithms like this are more likely to be used only in specialized situations where Zeckendorf arithmetic is relevant, like the analysis of certain combinatorial games.

-

Connor Ahlbach, Jeremy Usatine, Christiane Frougny, and Nicholas Pippenger (2013), “Efficient algorithms for Zeckendorf arithmetic”, Fibonacci Quarterly 51 (3): 249–255, arXiv:1207.4497, MR3093678. ↩

-

Anders Björner, László Lovász, and Peter Shor (1991), “Chip-firing games on graphs”, European Journal on Combinatorics 12 (4): 283–291, doi:10.1016/S0195-6698(13)80111-4, MR1120415. ↩

-

Kolja Knauer (2009), “Chip-firing, antimatroids, and polyhedra”, EuroComb 2009, Electronic Notes in Discrete Mathematics 34: 9–13, doi:10.1016/j.endm.2009.07.002, MR2591410. ↩

-

I. S. Sergeev (2018), “On the complexity of Fibonacci coding”, Problems of Information Transmission 54: 343–350, doi:10.1134/S0032946018040038, MR3917588. ↩