Constant width from involutes of pseudotriangles

In his online collection of fun stuff, Jeff Edmonds recently posted a method of constructing curves of constant width by spinning a pencil on a flat surface, with a varying axis, and tracking the movement of its ends. It is pretty similar to the classical method of crossed lines described by Martin Gardner in The Unexpected Hanging, in which one constructs an arrangement of lines in the plane, sorts them in circular order by slope, and builds a curve out of circular arcs centered at the crossing points of consecutive lines in this sorted order. However, it grows the curve at both ends simultaneously, rather than only at one end, and chooses the lines dynamically rather than in advance. Regardless, the result is the same: a piecewise-circular constant-width curve.

This got me wondering how we might go about constructing curves of constant width that are not piecewise-circular. Instead of a finite set of lines, we could use a continuous family of lines, one of each slope, but that’s a little difficult to visualize. Instead, there’s a simpler method that works more like Jeff’s spinning pencil, which Robinson (“Smooth curves of constant width and transnormality”, Bull. LMS 1984) attributes to Euler (“De curvis triangularibus”, 1778):

-

Draw a closed curve in the plane that has only one tangent line of each slope.

-

Rotate a “long enough” tangent line segment of some fixed length around this curve without sliding it.

-

Trace the paths of the endpoints of the line segment.

The first step may already seem a little confusing. Don’t curves usually have at least two tangent lines of each slope, their support lines from opposite sides? Well, yes, for convex curves. But for a pseudotriangle, a curve whose boundary is concave everywhere except at three extreme points, there might only be one tangent line of each slope. A standard example of such a curve is the deltoid, and the following animation stolen from the mathcurve.com page on deltoids shows a tangent line segment (black) rotating around a deltoid (blue) and tracing out a curve of constant width (red).

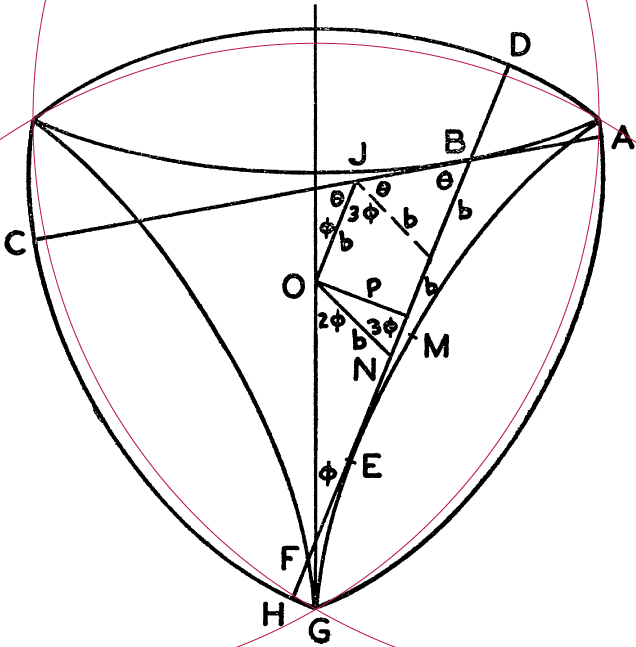

The traced curve is always perpendicular to the rotating line segment, so locally at least this segment behaves like the width of the curve in each given direction. And since we don’t change the length of the segment while it rotates, the width stays constant. The same deltoid, the same curve of constant width, and two positions of its tangent line segment can also be seen in the illustration below from a 1954 mathematics paper, “Rotors within rotors” by Michael Goldberg in the Amer. Math. Monthly. I’ve overlaid a red Reuleaux triangle to show that, like so many other curvy triangles, this is not a Reuleaux triangle, even though it has constant width. Although its corners are drawn to look kind of pointy, they should actually be smooth, and the rest of the curve bulges farther out from its sides than a Reuleaux triangle would.

More formally, this process of rotating and tracing tangent line segments produces a curve called the involute of the deltoid. An involute of a curve is more typically described as what you get when you fix one end of a length of string at a point on the curve, wrap it tightly around the curve, and then unwrap it while keeping it taut, tracing a curve with the other end of the string as you do. The two ends of the rotating tangent line segment can both be thought of as being formed in the same way from two strings, with one of them unwrapping the deltoid from one direction while the other wraps it back up in the other direction. In the deltoid example the segment was the same length as the sides of the deltoid, which were all equal, but it also works with unequal sides or longer segments, as long as the rotating segment is long enough to reach all three cusps.

You might worry whether the segment always comes back to its starting position after each rotation, and this does require a little care in the initial choice of length and placement of the line segment. If the length of the rotating segment and eventual width of the traced curve are \(w\), the pseudotriangle sides have lengths \(a\), \(b\), and \(c\), and the segment starts with \(x\) units of extra length extending past the cusp prior to side \(a\) in its rotation, then it will have \(w-a-x\) units of extra length at the next cusp, \(w-b-(w-a-x)=x+a-b\) units at the third cusp, and \(w-c-(x+a-b)=w-x-a+b-c\) units at the last cusp. To make a curve of constant width we need the amount of extra length at the start and end to be equal, which happens when we set this length to be \(x=(w-a+b-c)/2\).

If the pseudotriangle that the tangent segment rotates around includes a line segment, there will be a discontinuity in its rotating movement as the axis of rotation shifts from one end of the segment to the other, much like the changes of axis described by Edmonds, but the same process still works. If the pseudotriangle has a point where its slope changes discontinuously (for instance, if it is a polygon rather than a smooth curve), then the rotating segment will rotate around this point, with its ends tracing circular arcs, as it continuously moves between the same slopes; this can happen either at the three convex points of the pseudotriangle or along the concave curves between them. In particular, if your pseudotriangle is actually an equilateral triangle and the rotating segment has the same length as its sides, you get a Reuleaux triangle.

It’s also possible to form closed curves with only one tangent line of each slope that are not pseudotriangles. An example is the standard pentagram (whose involute is the Reuleaux pentagon), or a cuspy and irregular pentagram like the one below (whose involute is another curve of constant width without circular arcs). The same process works for these, with a slightly more complicated calculation of how to place a rotating segment of a given length for a given starting curve, involving alternating sums of side lengths.

What happens when the rotating line segment is too short, so that it doesn’t reach one or more of the cusps? I’m not sure in general, but for the deltoid the result can be the same deltoid (for which the rotating line segment is one possibility for Goldberg’s “rotor within a rotor”, although the rotor he describes is larger) or another similar but smaller deltoid inside it. See the mathcurve link for details.