Stable-marriage Voronoi diagrams

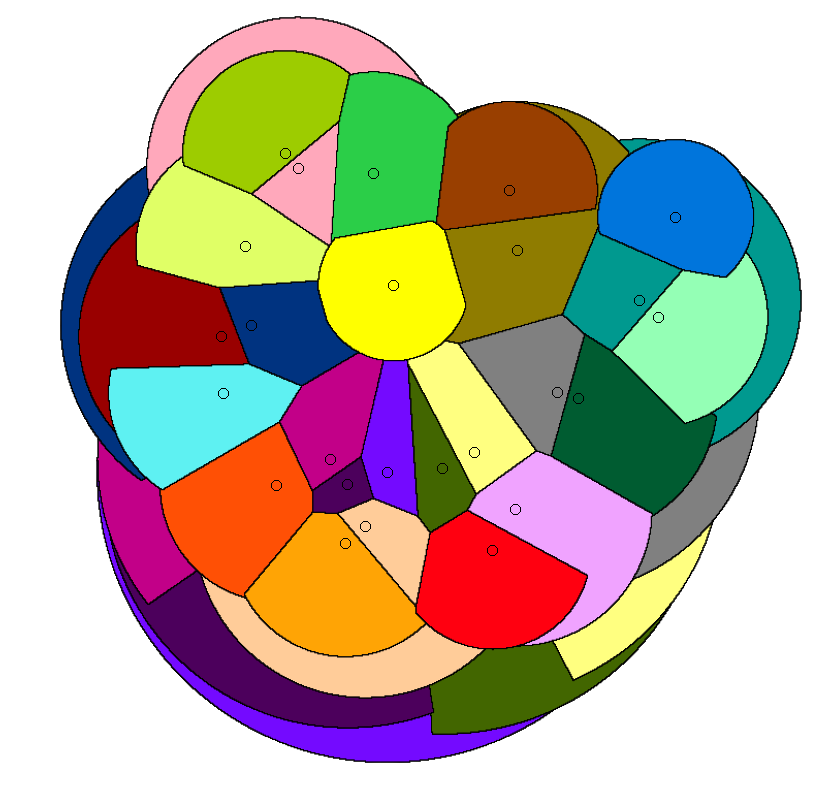

My student Nil Mamano, Mike Goodrich, Gil Barequet, and I have another preprint in our series of papers on geometric stable marriage problems: “Stable-Matching Voronoi Diagrams: Combinatorial Complexity and Algorithms” (arXiv:1804.09411, to appear in ICALP). In these problems, we are matching points in the plane (or in a smaller geometric region) to a finite set of sites, so that each site is assigned a region of a specified area (often, equal areas to all sites) and there is no unstable point-site pair (a pair closer to each other than the assigned site of the point and than the farthest assigned point of the site). Our goal in this work has been to find a natural way of subdividing geographic regions into compact districts of equal sizes (with size measured by arbitrary measures such as population, not just area), such as one would want to do in political redistricting. So far, though, we’re not yet at a point where our methods can be applied for these problems, in part because the partitions we get are somewhat messy. For instance, it is common to have disconnected regions, such as the salmon region in the upper left or the pale yellow region in the center and lower right of this diagram:

When we first started working on these topics, we shied away from handling the point side of these matching problems using continuous methods. Instead, we discretized the region to be matched as a grid of pixels, and considered only algorithms that find the matching pixel-by-pixel. Later, we shifted our interest to road networks and road-network distance, matching points of these networks to a selected subset of centers and developing data structures for dynamic nearest neighbors in planar graphs to use as a subroutine in our matching algorithms.

In the new paper we’ve returned to the Euclidean distance version of the problem, treated in exact terms rather than as a pixelized approximation. From this point of view, natural questions to ask include: What is the combinatorial complexity of this diagram? What sort of numbers do we need to represent its coordinates? What geometric primitives suffice to construct it, and how many computational steps are needed for the construction?

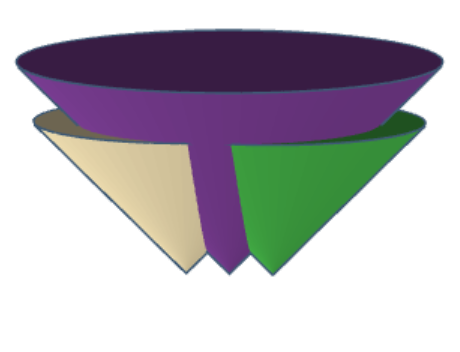

For standard Voronoi diagrams, there is a way of looking at the problem in 3d instead of 2d that can be very helpful. Embed the plane (in which the Voronoi diagram is to be constructed) as the \(xy\)-coordinate plane of 3d Euclidean space. Above each of the sites, construct a cone, with a 45-degree opening angle: this is the graph of the function that maps each point of the plane to its distance from the site. Then the Voronoi diagram is the lower envelope of these cones, what you would see if you look up at them. For the stable-matching Voronoi diagram, too, there is a set of cones whose lower envelope is the diagram, but they end at a finite height rather than continuing upward infinitely. Here they are (for a simpler diagram) from a side view:

To construct the cones and the diagram (conceptually, not algorithmically), start growing them all from very small cones, at the same rate, and stop each cone from growing when the area directly under it equals the area we want its site to have. The growth of the remaining cones cannot cause them to take away any of this area, so we end up with a diagram in which all sites have the correct area, and which turns out to be stable.

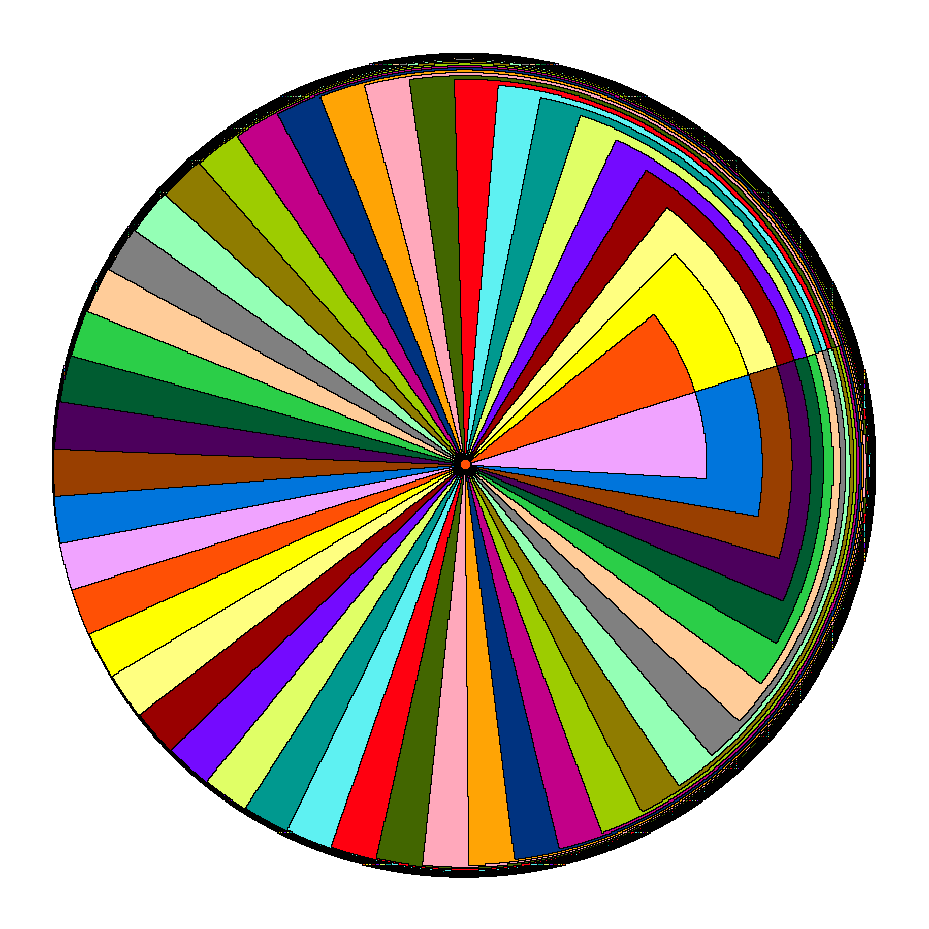

There’s a general theory of lower envelopes of piecewise-algebraic surfaces, bounded by piecewise-algebraic curves (as these cones are) that tells us that the lower envelope has \(O(n^{2+\epsilon})\) features, for all \(\epsilon>0\). To show that this is nearly tight for the stable-marriage Voronoi diagram, we constructed diagrams whose combinatorial complexity is \(\Omega(n^2)\). The basic idea is to use a cluster of tightly spaced sites to create features of the diagram that look like rainbows, with many nearly-concentric circular arcs separating one site’s region from another, and then to use another subset of sites to take bites out of the rainbow. There can be linearly many bites, each having a linear number of rainbow features on its boundary, giving us quadratic overall complexity. First, here’s the part where we construct the rainbow:

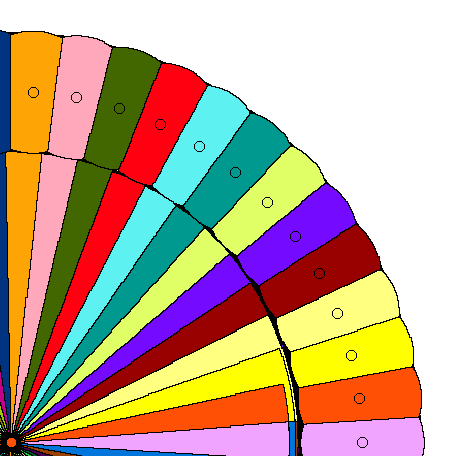

And here’s the part where we add another ring of sites, outside the rainbow, to take bites out of it:

To compute the diagram, we use the same idea of building cones in 3d, in a slightly different way. We start out with all cones infinite (generating a Voronoi diagram) and then repeatedly cut them down to a finite size. At each step, for each remaining infinite cone, we compute the radius for which the part of the current diagram within that radius already satisfies its site’s area goal. The site whose radius is minimum is the one we cut, and then we continue in the same way in the remaining lower envelope. Unfortunately computing the appropriate radius for each site involves messy transcendental numbers (it is not algebraic) but if we take that as a primitive operation the algorithm can be performed in a polynomial number of steps. We would like it to be quadratic, matching the combinatorial complexity of the diagram, but it looks more like cubic. So there’s still more work to be done, both in closing the gap between our upper and lower bounds on the combinatorial complexity of these diagrams, and in making our algorithm more efficient.

(G+)