Enumerating polyhedra with few edge lengths

This is related to my post yesterday, which demonstrated that simplicial convex polyhedra (all faces are triangles) with integer edge lengths can be forced to have nasty vertex coordinates, without any closed form solution. How big do the edge lengths need to be for this to happen? My guess is that lengths 1 and 2 should be enough, but I haven't worked out an explicit example. But length 1 alone is not enough.

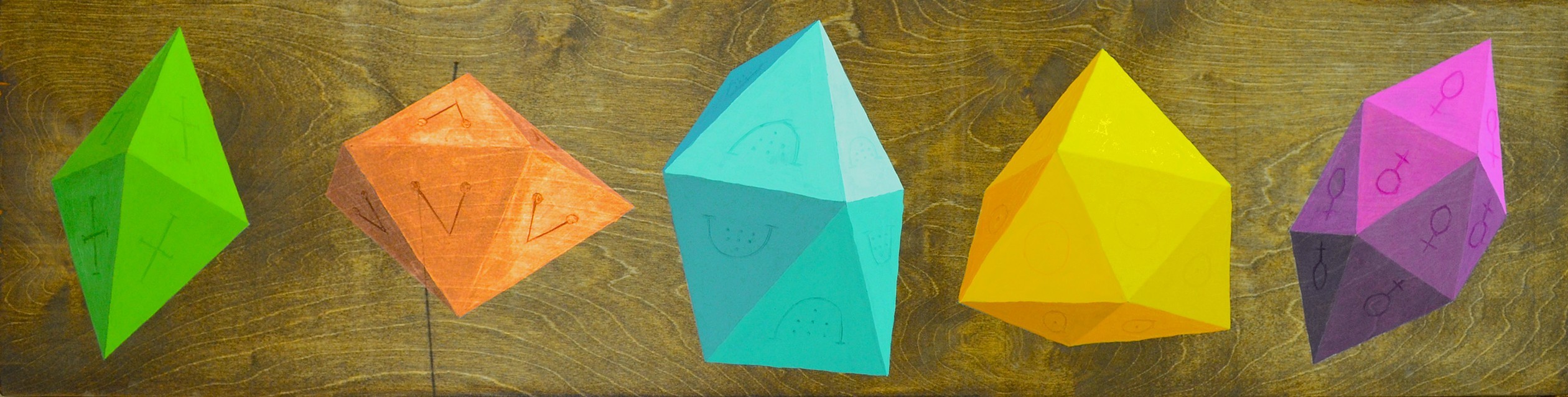

The simplicial polyhedra with all edge lengths 1 are called deltahedra, and there are only eight of them. They include three of the regular polyhedra, and five others shown below in a Neo-Platonist artwork by Brian Hofmeister (see his web site for more interesting geometric art):

Most of the irregular deltahedra can be built out of simpler pieces, prisms and pyramids, and have relatively simple vertex coordinates. The snub disphenoid, the light blue one in the middle, has coordinates that are more of a mess, involving the solution to a cubic equation, but still closed form.

So next we need to look at polyhedra with edge lengths \( 1 \) and \( 2 \), but there are many of them and I don't think they have been explicitly enumerated. How many? Finitely many, but I don't know much more than that.

More generally, suppose you have finitely many edge lengths to use as the side lengths of your triangles. For instance, in my office I have a polyhedral construction set consisting of triangles (and some other polygons) with sides that are all either \( 1 \) or \( \sqrt{2} \) (in some system of measurement). Then there are finitely many triangles you can build from these lengths, and finitely many combinations of triangles you can put together at a single vertex to get a total angle that is strictly less than \( 2\pi \) (else you can't use that combination in a convex polyhedron). Because there are finitely many, there is some nonzero number \( \epsilon \) that gives the smallest angular defect (difference from \( 2\pi \)) of any of these combinations of triangles.

But every convex polyhedron has total angular defect \( 4\pi \), by a discrete version of the Gauss–Bonnet theorem. This means that the total number of vertices can never be more than \( 4\pi/\epsilon \), a finite number. And with finitely many vertices you can only have finitely many different polyhedra.

This argument is not very constructive. As I've written it above, it doesn't tell you how quickly the number of integer-sided simplicial polyhedra grows as a function of the maximum edge length, for instance. And if you try to use this method to prove a bound on the growth rate, you quickly run into tricky problems in diophantine approximation: just how close can you get to zero defect while still having positive defect? I can't even tell from this argument whether the \( 1 \)—\( \sqrt{2} \) triangles in my office can make more convex polyhedra than \( 1 \)—\( 2 \) triangles. (Note, though, that any bound has to involve the lengths and not just the number of different edge lengths, because a \( 1 \)—\( n \)—\( n \) isosceles triangle can make a number of different bipyramids that's linear in \( n \).) So there's a lot of scope for more research in this area.

Comments:

2015-12-08T23:04:03Z

If you allow coplanar facets, you can build any integer-sided rectangular box using only edge lengths \( 1 \) and \( \sqrt{2} \).

So as \( \epsilon\gt 0 \) goes to zero, does the number of (strictly) convex polyhedra with edge lengths \( 1 \) and \( \sqrt{2}+\epsilon \) grow to infinity?

2015-12-08T23:16:18Z

I don't think so. For these edge lengths, there are several ways to get an angular defect close to zero, but they all involve using \( 1 \)–\( 1 \)–\( (\sqrt{2}+\epsilon) \) triangles, and more specifically using more than twice as many sharp angles of these triangles as obtuse angles from the same triangles. So every time you do this you need to make up for the imbalance by using more obtuse angles than sharp angles elsewhere, and getting a vertex whose angular defect is bounded away from zero.