Kinematic chains and their graphs

Like most universities, UCI has a requirement that doctoral students get someone outside their own school to serve on their committees (only for us it's the candidacy committee instead of as most other places the thesis committee). Anyway, last week I found myself on the committee of a student in mechanical engineering, whose research project involves developing software to analyze the motion of mechanical linkages formed by systems of linked rigid bodies. In the class of systems he was interested in, the rigid bodies (links) lie in a plane, although they may cross each other. Pairs of links are connected at joints that restrict their relative motion to be a rotation, and (if one of the links is fixed in place) the whole system should have only one degree of freedom. A pair of scissors gives a familiar example with two links and one joint. Apparently car trunk lids are usually connected to the car body using four-bar linkages – at least, mine appears to be – and one of the other engineers at the exam said this was because a simple hinge would cause the lid to bump into the rear window of the car. Here are a couple of more complicated examples, with eight links:

The graphs next to each of these two linkages have a vertex for each link and an edge for each joint. The graphs formed from a linkage in this way turn out to be exactly the \( (3/2,2) \)-tight graphs, meaning that each \( k \)-vertex subgraph has at most \( (3/2) k - 2 \) edges and that the whole \( n \)-vertex graph has exactly \( (3/2) n - 2 \) edges. The restriction on the subgraphs is to prevent any subgraph from being rigid (in which case we might as well treat it as just a single link) and the restriction on the number of edges on the whole graph is to give it the correct number of degrees of freedom. Every graph of this type has an even number of vertices. The numbers of different graphs grow rapidly, as a function of the number of vertices: they are (starting with the two-vertex graph and progressing by two more vertices at each step) \[ 1, 1, 2, 16, 230, 6856, 318162, 19819281, \] and after that we don't know. However, most of these graphs can be built up in a simpler way from smaller graphs: if \( G \) and \( H \) are both \( (3/2,2) \)-tight, you can form another \( (3/2,2) \)-tight graph by removing an edge from \( G \) and identifying its endpoints with an arbitrary pair of vertices in \( H \). There are a smaller number of graphs that are prime with respect to this sort of decomposition, which include the graph with two vertices, the four-vertex cycle, and the two 8-vertex subdivisions of \( K_4 \) shown above.

If we're given a graph, how can we tell whether it's one of these \( (3/2,2) \)-tight graphs? There's an answer in a 2008 paper of Lee and Streinu, "Pebble game algorithms and sparse graphs". This paper gives an algorithm for testing \( (a,b) \)-tightness for certain integer combinations of \( a \) and \( b \), but it can easily be adapted to deal with fractional values such as \( 3/2 \), by making two copies of each edge and treating it as a \( (3,4) \)-tight multigraph. Testing a graph for tightness is performed by a "pebble game" in which we start with an empty graph (one with \( n \) vertices, pebbles on the vertices, and no edges) and follow certain rules for moving pebbles around and trading pebbles for vertices until eventually reaching the desired graph. For testing \( (3/2,2) \)-tightness, the pebble game starts out with three pebbles per vertex (represented by the value of a counter). A pebble may move backwards along a directed edge, causing the edge's direction to flip, as long as this does not result in more than three pebbles at its destination. And if two vertices together have five or more pebbles, we can add a directed edge between them, removing one pebble at the start vertex of the edge.

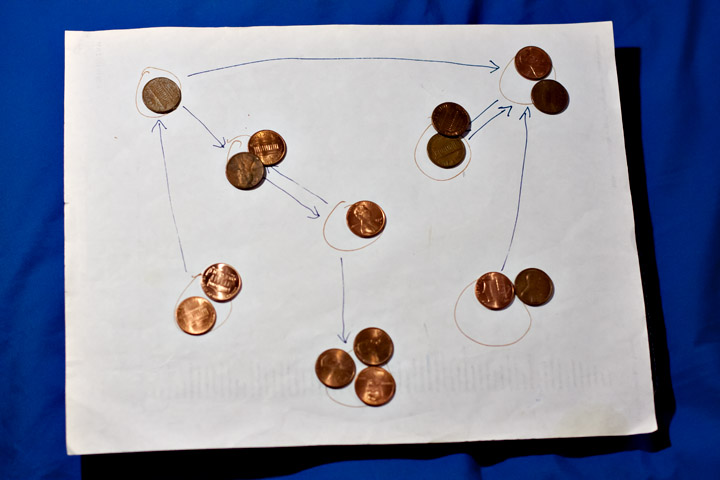

Here's an example where I tried following these rules to create the top right graph, using pennies in place of pebbles. So far, I haven't had to reverse any edges, but there are only two more edges I can create without reversals, so it's about to get a lot messier. To simulate this more easily by hand, you should probably use movable markers for the arrowheads as well as for the pebbles.

Based on these rules, the algorithm for testing \( (3/2,2) \)-tightness performs the following steps. It initializes an empty graph with three pebbles per vertex. It then loops through the edges of the doubled graph (i.e. it considers each input edge twice). When considering an edge (\( u \),\( v \)), if there are not already enough (five) pebbles present at \( u \) and \( v \) to create the edge, it does a depth-first search on the outgoing edges from \( u \) and \( v \) to find more pebbles that can be moved to \( u \) and \( v \) (if necessary also rebalancing the pebbles between \( u \) and \( v \) to avoid putting too many on one vertex). If this search fails to find enough pebbles it rejects the graph. Then it creates the edge, choosing a direction for it arbitrarily and removing a pebble from the starting vertex of the directed edge. If this process succeeds in creating all the input edges (twice each), with exactly four pebbles left at the end, then the input graph is \( (3/2,2) \)-tight. This all takes at most \( O(n^2) \) time; Lee and Streinu go on to describe how to modify the algorithm to detect rigid components of a graph that may not itself be sparse, in the same running time.

Comments:

2013-12-15T03:15:49Z

Heh. I've been enjoying your blog for a few years, but it gave me a bit of a start when I saw the sequence you posted here. "Hey, I wrote a paper on that!"

It's sort of amusing, I've always felt like I should submit at least one sequence to OEIS, and yet somehow when I cowrote a paper on something that actually belongs there (equal work, but my co-author, a mechanical engineer introduced the topic to me), I forgot all about it. The methods we used should be capable of figuring out the next term in the sequence today, with greater computing power (it was close before) but I've lost interest. The mechanical engineers don't really want to use 16-bar mechanisms anyway, and others are doing very nice work on atlases of the smaller possibilities.