Which infinite graphs are chordal?

Many facts and definitions that seem straightforward for finite graphs can become much messier when infinite graphs get involved. As a case in point, I've been thinking about chordal graphs.

There are multiple equivalent definitions that work equally well for finite chordal graphs:

- They are the graphs in which every cycle of length greater than three has a chord, an edge connecting two vertices that are not consecutive in the cycle.

- They are the graphs in which every induced subgraph has a simplicial vertex, a vertex all of whose neighbors form a clique.

- They are the graphs that have an elimination ordering, a total ordering on the vertices in which, for every vertex \( v, \) the neighbors of \( v \) that are later in the ordering form a clique.

- They are the intersection graphs of subtrees of a tree: the vertices of the graph can be mapped to subtrees of a tree, such that two vertices are adjacent if and only if their subtrees overlap.

For infinite graphs, these are not equivalent. A doubly-infinite path does not have any simplicial vertices, but satisfies all the other properties. A complete graph whose set of vertices cannot be totally ordered (in models of set theory in which the ordering principle fails) does not have an elimination ordering, but satisfies all the other properties.

It's not even clear what it means to be a tree or a subtree of it: is it a connected undirected acyclic graph? Must it have bounded diameter? Does a real tree count as a tree? Should we define (rooted) trees as directed graphs, or as real trees, or should we instead use their reachability partial orderings? A finite partial order \( (P,\le) \) represents a forest (with leaves as its minimal elements) if and only if, for every \( x, \) \( y, \) and \( z, \) \(x\le y\) and \(x\le z\) together imply that either \(y\le z\) or \(z\le y.\) In a forest partial order, a subtree can be represented as a set of elements with a maximum (root) \(r,\) such that for any two other elements of the order \(x\) and \(y\) with \(x\le y\le r,\) if \(x\) is in the subtree then so is \(y.\) However, infinite partially ordered sets that satisfy the same axioms may come from structures like the real number line that don't look like graphs.

In this case, it seems that some simplification and unification is possible based on the theory of well-orderings, total orders that do not have any infinite descending chains (or equivalently in which every set has a minimum element). If the axiom of choice is true, every set has a well-ordering, but we can also make that assumption explicit. If we do, we get the following three definitions, which turn out to be equivalent to each other.

- The graphs whose vertex sets are well-orderable, in which every induced subgraph has a simplicial vertex.

- The graphs that have a well-ordering of the vertices for which, for every vertex \( v, \) the later neighbors of \( v \) form a clique.

- The graphs whose vertex sets are well-orderable, that are the intersection graphs of subtrees of well-ordered forest partial orders (forest partial orders with a compatible well-ordering).

Proof sketch for \( (6) \Rightarrow (5)\): Suppose that a graph \( G \) has a well-elimination ordering. Then if \( S \) is any subset of the vertices, the vertex in \( S \) that's first according to the ordering must be simplicial in \( S. \)

Proof sketch for \( (5) \Rightarrow (6)\): Let \(\le\) be a well-ordering of \(G\) (not necessarily an elimination ordering). Let \(S\) be the set of well-orderings of subsets of \(G\) such that (a) each well-ordering in \(S\) is, as far as it goes, an elimination ordering, and (b) each well-ordering in \(S\) is lexicographically minimal, in that it is not possible to truncate the ordering at some vertex of \(G\) and replace that vertex by an earlier vertex in \(\le\) while preserving the elimination ordering property. Then the elements of \(S\) are linearly ordered by being extensions of each other, and this linear ordering places them in one-to-one correspondence with some prefix of the ordinals. By transfinite induction there is a maximal element in \(S.\) If this maximal element did not include all of \(G,\) then it could be extended by adding the smallest simplicial vertex in the remaining set of vertices, violating maximality. Therefore, it is a well elimination ordering for all of \(G.\)

Proof sketch for \((6) \Rightarrow (7)\): Suppose that a graph \(G\) has a well-elimination ordering. Define a binary relation \(R\) whose elements are the vertices of \(G,\) in which \(xRy\) whenever \(x\) and \(y\) are neighbors in \(G\) and \(x\) is earlier than \(y\) in the elimination ordering. Let \(\le\) be the transitive closure of \(R\) (the relation in which \(x\le y\) whenever there is a finite chain \(xRa, aRb, bRc, cRy\) etc.) Then \(\le\) is a forest order compatible with the well-elimination ordering, for each \(v\) the set of \(v\) and its earlier neighbors is a subtree, and \(G\) is the intersection graph of these subtrees.

Proof sketch for \((7) \Rightarrow (5)\): Suppose that \(G\) is the intersection graph of paths in a well-ordered forest order. If \(S\) is any set of vertices of \(G,\) let \(v\) be the vertex in \(S\) whose subtree root \(r\) is earliest in the order. Then \(v\) must be simplicial in \(S,\) because all its neighbors are represented by subtrees that contain \(r.\)

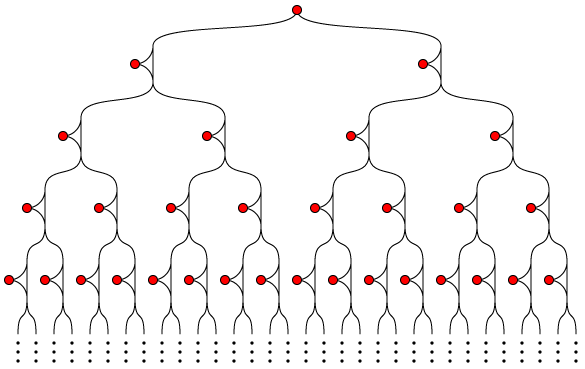

The fact that this nice equivalence exists makes me think that (5), (6), and (7) are a good definition for the infinite chordal graphs (though maybe they should be called something else since they're not using the chordal property). But what I'm missing is another equivalent analogous to (1). What are the forbidden induced subgraphs for these infinite graphs? Along with the chordless cycles they also include doubly-infinite chordless paths, and any graph whose set of vertices cannot be well-ordered. But those aren't the only forbidden subgraphs. For instance, the confluent drawing below shows a graph (derived in the manner of trivially perfect graphs from an infinite tree that's well-ordered in the wrong direction, towards the root rather than towards the leaves) that does not have any of these other forbidden subgraphs but also does not have any simplicial vertices.

This graph has infinitely many different induced subgraphs that, like it, have no simplicial vertices, but all of these subgraphs in turn have the graph itself as an induced subgraph. Is it possible to catalog all the forbidden induced subgraphs for the graphs satisfying definitions (5), (6), and (7)?

Comments:

2011-11-17T01:45:39Z

I enjoyed this post very much. I have previously spent some time thinking about perfect graphs (and so chordal graphs along the way), but also extending matroid axioms to infinite sets, so it was interesting.

I hate to be the nitpicking type, but your phrasing seemed a bit off in two side comments: "too large to be totally ordered" and "too large to be well-ordered". Perhaps you're aware and simply avoiding technical points, but in case you're not:

Being large isn't really an obstruction to being (well-)ordered. There are plenty of large, well-orderable sets, for example any set of ordinals. (Indeed, the entire proper class of ordinals is well-ordered.) This can be made precise: for any set \( S, \) there exists a well-orderable set \( T \) such that \( T \) is not less than \( S \) in the sense of cardinals. (One can't hope for "is not less than" to be replaced with "is larger than" for the usual axiom of choice reasons.)

2011-11-17T01:57:52Z

Thanks for the correction — I was just being sloppy rather than unaware, sorry about that.

I was coming at this from the point of view of extending antimatroid axioms to infinite sets, actually. Elimination orderings of chordal graphs were an example I was using to think about antimatroids. The usual antimatroid axioms for set systems (closed under union, and every set has a removable element) don't work very well because you can't get very far removing only one element at a time without limits. I think the right approach is instead to formalize the idea that an antimatroid is a way of describing sets of orderings in which an element, once available to be added to the ordering, stays available until it actually is added.

The system of axioms I came up with is that an infinite antimatroid is a family of subsets of a well-orderable set that contains the empty set and the whole set, is closed under unions, and has the property that whenever sets \( S \) and \( T \) both belong to the family with \( S \) a subset of \( T, \) then there is an element \( x \) of \( T \setminus S \) that can be added to \( S \) to make another set in that family.

With these axioms, an argument much like the \( (5) \Rightarrow (6)\) one above shows that any family of sets with these properties has a (unique lexicographically minimal) well-ordering such that every prefix of the ordering defines a set in the family.

2011-11-17T02:39:29Z

This is very interesting! Coincidentally, I recently had to consider the same question. However, the generalization I obtained is somewhat different. It can be found in my recent paper 'A note on conjectures of F. Galvin and R. Rado' (arXiv:1110.6563 and DOI:10.4153/CMB-2011-192-8). My version was guided by infinite comparability graphs and interval graphs.

Obviously, a comparability graph, finite or infinite, is a graph with a transitive orientation. There is another characterization, which is well known in the finite case, every odd cycle of length 5 or more has a triangular chord. This is a characterization in the infinite case too by a compactness argument.

Similarly, an interval graph, finite or infinite, is the intersection graph of some family of convex subsets of a linear order. There are a few well known characterizations of finite interval graphs too, a useful one is that they are chordal graphs whose complements are comparability graphs. This also characterizes infinite interval graphs, where chordal is taken to mean that every cycle of length 4 or more has a chord.

From this, I inferred that the correct definition of chordal in the infinite case is the first, every cycle of length 4 or more has a chord. I then tried to generalize the second and third characterizations. It worked, but in a slightly different way than yours:

(2') Graphs in which every finite induced subgraph has a simplcial vertex.

(3') Graphs in that have a simplicial orientation, an acyclic orientation such that the in-neighbors of a vertex always form a clique (in the unoriented graph).

A linear extension of the transitive closure of a simplicial orientation has the property that the neighbors of a vertex that precede it in the ordering form a clique. This is like the elimination property, but I wouldn't call it that since the process of elimination it refers to suggests a wellordering, which is not necessarily the case here.

The equivalence of (1) and (2') follows from the finite case, and the equivalence with (3') is a compactness argument. I hadn't really considered the fourth characterization, but I did actually carry out the core of the equivalence in my paper (Theorem 4.3, which works much like your sketch).

Anyway, I like your generalization too! I'm really happy to learn about this alternate generalization. In fact, I think your version (4) could have been handy in the very last part of my paper...

PS: Since you seem to be concerned with choice, the equivalence of (1), (2'), (3') and (4') uses no more than the Boolean Prime Ideal Theorem to get from (2') to (3').

2011-11-17T03:11:30Z

Thanks for the references and the interesting comments.

I was thinking that the no chordless cycles definition that you prefer may also be enough to get something like an elimination ordering, but with an additional technical assumption that (the vertices are well-orderable and) there are no complete bipartite subgraphs with both sides infinite. With this assumption, one can define a LexBFS well-ordering, and (if there are no chordless cycles) its reversal should be an elimination ordering. I haven't worked out the details, so I could easily be missing something. But if this works, it would strengthen your argument about topological orderings (=linear extensions of transitive closures) in that you do get a well-ordering, but in the opposite direction to the one in my definition (6).