How to lie with geometric illustrations

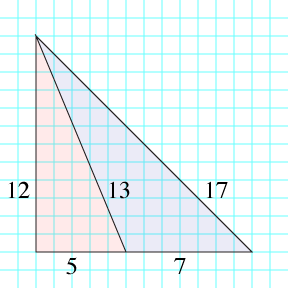

(5,12,13) is a famous Pythagorean triple, and (7,13,17) are the sides of the smallest integer automedian triangle, derived from the 5-12-13 right triangle.

And of course the figure above isn't accurate: in the drawing, the longest edge has length 16.97 instead of exactly 17.

I'm not sure whether this is an isolated oddity or whether there are more pairs of integer Pythagorean and automedian triangles whose angles almost match up like these two do.

Comments:

2011-11-08T20:43:18Z

It's not an isolated oddity; the automedian triangle off an 8-15-17 triangle is a 7-17-22, where the longest edge in the corresponding diagram is about 21.2. So, not quite as close, but not horribly off either.

An effect of the method of generating an automedian triangle from a right triangle of sides \( x \) and \( y \) (with \( y \gt x \)) and hypotenuse \( z \) is that the combination of the right triangle and "blue" triangle (as in your illustration above) is an isoceles right triangle. Thus, the longest side on the "blue" triangle is \( y\sqrt{2}, \) and the longest side on the automedian triangle is \( x + y. \) So, the triangles will be close when \( x \) is approximately \( (\sqrt{2} - 1) y. \)

I assume you can have an infinite number of integer right triangles that are arbitrarily close to a given side ratio (since Wikipedia gives examples for \( 1:2:\sqrt{5} \) and \( 1:1:\sqrt{2} \) cases), so I think the answer to your question is that this is indeed not an isolated oddity at all.

2011-11-08T21:10:21Z

Yes, you can find integer right triangles that are arbitrarily close in shape to any given right triangle. But I think that it may not be possible to find infinitely many examples (or even, any other examples) where the squared length of the true isosceles right triangle (here 288) and the squared length of the longest side of the blue triangle (here 289) differ only by one. I tried looking at the next few pairs of Pell numbers since those are the ones that give rise to the most accurate integer approximations to \( \sqrt{2} \) but none of the pairs after (5,12) had the property of belonging to a Pythagorean triple.

2011-11-08T22:20:14Z

If we only generate automedian triangles using the correspondence suggested by brooksmoses, then an original right triangle with sides \( a, b, c \) gives rise to an automedian with sides \( c, b-a, b+a \) and an "isosceles" right triangle with sides \( b, b, b+a. \)

If we want the difference from Pythagoras to be 1, then we'd better have a primitive right triangle to start. Writing \( b=2mn \) and \( a=m^2-n^2 \) gives that

\[ (b+a)^2-2b^2=m^2+4m^3n-6m^2n^2-4mn^3+n^4 =n^4(r^4+4r^3-6r^2-4r+1), \]where \( r=m/n. \) The root of this quartic is about 1.4966 (which is exceptionally well approximated by 3/2, giving the (5,12) example). Continued fractions normally would only give a \( 1/n^2 \) approximation, and here we need a \( 1/n^4, \) which seems unlikely (though I certainly can't prove anything...)

2011-11-08T22:46:57Z

Requiring that the squares of the sides differ by less than one does seem difficult, but that seems irrelevant to why the illustration "works", which is that the difference is very small relative to the length of the longest side.

automedian 889 1825 2423

right 984 1537 1825

The difference here slightly larger in absolute terms (0.089) but much lower relative to the length of the hypotenuse.