Algorithms inspired by TRON

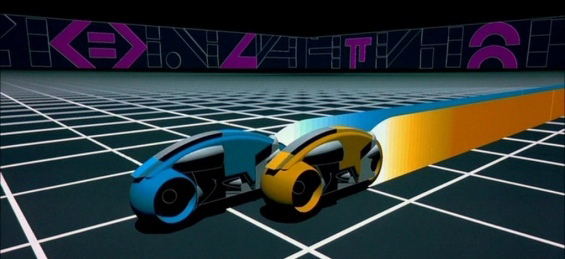

I've posted a bit about this before, but I thought that next week's release of TRON: Legacy would make a good excuse to write about motorcycle graphs, a geometric structure inspired by the original TRON movie.

In the video-game world of TRON, one of the games involves "light cycles", motorcycles that leave wall-like trails behind them. You lose by crashing into the trail of your opponent, and you win by leaving trails that box your opponent in, forcing him or her to crash.

Based on this idea, in 1998 or so, Jeff Erickson defined motorcycle graphs to be the system of trails left behind by a set of motorcycles, modeled as linearly moving points in the Euclidean plane, that stop when they run into the trail of another motorcycle. Unlike the light cycles in TRON, the motorcycles that form a motorcycle graph don't turn, they can move in arbitrary directions rather than being restricted to being axis-parallel, they can have differing speeds from each other, and their trails don't vanish after they crash.

For an online demo in which you can set up your own system of moving motorcycles and build their motorcycle graph (in rather plain graphics) see here.

One can represent the resulting structure as a graph, with a vertex for each starting and ending point of each motorcycle, and edges for the straight line segments followed by the motorcycles between these points. The trail of any motorcycle is partitioned into this way into segments between the points where other motorcycles will later crash into the trail. This graph can have cycles: it is possible for all players to lose the game by crashing into the trail previously left by another player. But it is a pseudoforest: each of its connected components has at most one cycle.

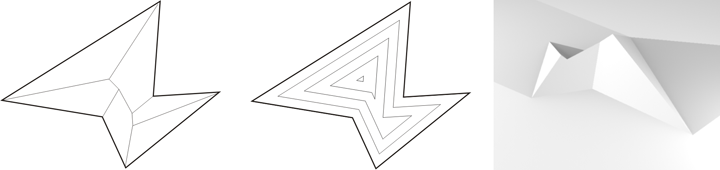

The original motivation for defining motorcycle graphs comes from the straight skeleton, a variant of the medial axis without curved segments that has found several applications in architectural design, geographic information systems, and mathematical origami. The straight skeleton of a polygon is defined by shrinking its edges inwards at a constant speed, and tracing out what happens to the vertices as the polygon shrinks. Each vertex moves linearly, but the vertex speeds can differ greatly depending on their angles. Convex vertices can merge, but concave vertices can also vanish more violently, by crashing into the opposite side of the polygon. The motorcycle graph provides a simplified model of this crashing process that could be helpful in developing efficient algorithms for straight skeletons.

In a paper I wrote with Jeff from SoCG 1999 on straight skeletons and motorcycle graphs, we showed that this "could be helpful" hope was true. Define a distance function on the motorcycles that define a motorcycle graph, in which the distance between two motorcycles is the amount of time it would take for one of them to crash into the trail of the other, assuming neither one of them crashed prior to that point. Then the process of forming the motorcycle graph can be simulated by repeatedly finding closest pairs according to this distance function. A data structure from a previous paper of mine transforms this dynamic closest pair problem into a dynamic nearest neighbor searching problem, which can then be solved by standard range searching techniques. Using these ideas, we were able to show how to construct both motorcycle graphs and straight skeletons in the somewhat ugly time bound \( O(n^{17/11+\varepsilon}) \). We also found faster algorithms for special cases of motorcycle graphs when all the motorcycles move at the same speed, all move in a constant number of distinct directions, or all move in the positive direction (east to west).

In 2002, Cheng and Vigneron developed a different technique to construct motorcycle graphs more quickly. They partition the plane into regions, such that only \( O(\sqrt{n}) \) motorcycle graphs can cross any individual region and each motorcycle crosses only \( O(\sqrt{n}) \) region boundaries. Then, they simulate a system of events that includes both the motorcycle crashes and the region crossings. Because there are few motorcycles within each region, the crashes can be found quickly without need for complex range searching structures, so the total time for their algorithm is \( O(n\sqrt{n}\log n) \). (It seems likely to me that one can do slightly better than this, by increasing the number of motorcycles per region and decreasing the number of crossing events, and using more complex data structures within each region, but I don't know of a paper that actually proves such an improvement.) They also show that the motorcycle graph is not just a simplified analogue of the straight skeleton, but that it can be used directly to guide the construction of the straight skeleton of a polygon without holes. After the motorcycle graph is found, the rest of their straight skeleton algorithm takes near-linear time. Later, at CCCG 2010, Huber and Held experimented with slower but even simpler algorithms for straight skeletons, again based on the connection with motorcycle graphs.

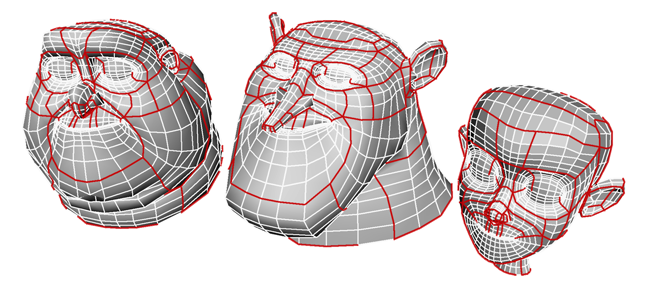

Finally, a different variation of motorcycle graphs has turned out to have some use in finite element meshing and computer graphics. This was the subject of my previous posting and of a paper at Geometry Processing 2008 by Mike Goodrich, Ethan Kim, and Rasmus Tamstorf, and myself. The problem considered in the paper is that of partitioning a three-dimensional surface made of quadrilaterals (as produced e.g. by Maya) into a smaller number of submeshes with the topology of a rectangular grid. One can do this, it turns out, with motorcycle graphs. Set up a collection of motorcycles that start out at the irregular vertices of the grid (the vertices that aren't surrounded by four quadrilaterals) and that move straight across each regular vertex until they hit another motorcycle or its trail; then the trails left by the motorcycles cut the mesh into regular submeshes. More, they do this in a canonical way (the same mesh topology always gives you the same partition) which makes the partition into submeshes usable as a compressed representation of the original mesh, speeding up other algorithms on these meshes such as testing graph isomorphism between pairs of meshes.

So, when you take off work to go see TRON: Legacy, just tell everyone it's research.

Comments:

2010-12-10T22:41:00Z

One of my most prized possessions is an autograph of Steve Lisberger, the director of TRON, on the first page of our straight-skeleton paper. (TRON was one of the movies at the first iteration of Roger Ebert's annual film festival in Champaign; Lisberger came to the screening. He was kind enough to accept a copy of the paper with my autograph on it as well.)

You worked on the mesh partitioning algorithms at Disney, right? Any chance they were actually used in TRON:Legacy? :-)

I recently discovered some relevant prior art. A nearly identical process has been used to study statistical properties of random crack networks since the mid-1960s, around the same time that random Voronoi diagrams were in their heyday. A Gilbert tesselation [1], also known as a random crack network [2], is formed by placing random points according to a homogeneous Poisson process, growing needles forward and backward at each point at unit speed in a uniformly random direction, and stopping the growth of any needle when it hits another needle. In other words, they're random unit-speed motorcycle graphs! More recently, Schreiber and Soja [3] look at statistical properties of "finite input Gilbert tessellations", which are essentially just random-direction unit-speed motorcycle graphs.

[1] E. N. Gilbert. Random plane networks and needle-shaped crystals. In Applications of Undergraduate Mathematics in Engineering (B. Noble, editor). Macmillan, New York, 1967.

[2] N. H. Gray, J. B. Anderson, J. D. Devine, and J. M. Kwasnik. Topological properties of random crack networks. Mathematical Geology 8(6):617–628, 1976.

[3] Tomasz Schreiber and Natalia Soja. Limit theory for planar Gilbert tessellations. arXiv:1005.0023, April 2010.

2010-12-10T22:56:50Z

Neat — I didn't know about that connection, and it's always very helpful to see similar things from different perspectives.

Yes, it was for Disney, but for their feature animation unit; I think that's different from the part of Disney that made TRON, so I don't know how likely it is that the algorithms got used there.