Orthogonal polyhedra

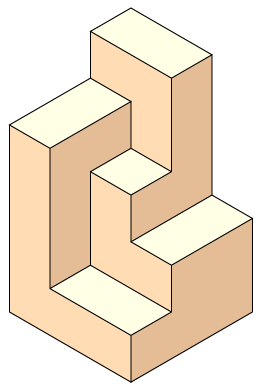

Three quick puzzles concerning the polycube depicted below: (1) Cut it into two pieces that can be reassembled into a cube. (2) Fill space with translated, rotated, and reflected copies of it. (3) Fill space with translated and rotated (but not reflected) copies of it.

This polyhedron is an axis-parallel permutohedron: its 24 vertices can be labeled with the 24 permutations on four objects, in such a way that each edge connects two permutations that are related by a swap of two adjacent values. My new paper with Elena Mumford, Steinitz Theorems for Orthogonal Polyhedra (arXiv:0912.0537), aims to provide a complete classification of orthogonal polyhedra such as this one in the same way that Steinitz's theorem provides a complete classification of convex polyhedra.

Convex polyhedra have graphs that are exactly the planar 3-connected graphs, from which we know that there is (up to combinatorial equivalence) only one four-face polyhedron (the tetrahedron), two five-face polyhedra (the triangular prism and the square pyramid), etc. The "simple orthogonal polyhedra" that we study in an analogous way have axis-parallel faces that are simple polygons, three perpendicular edges at each vertex, and the topology of the sphere. As we show, these polyhedra are exactly described by the planar bipartite 3-regular graphs with a weaker connectivity condition than Steinitz's: removing any two vertices splits the graph into at most two connected components (counting an edge between the two removed vertices as a component). From this graph-theoretic characterization it follows that there is exactly one six-face orthogonal polyhedron (the cube), one eight-face orthogonal polyhedron (an L-shaped hexagonal prism), etc.

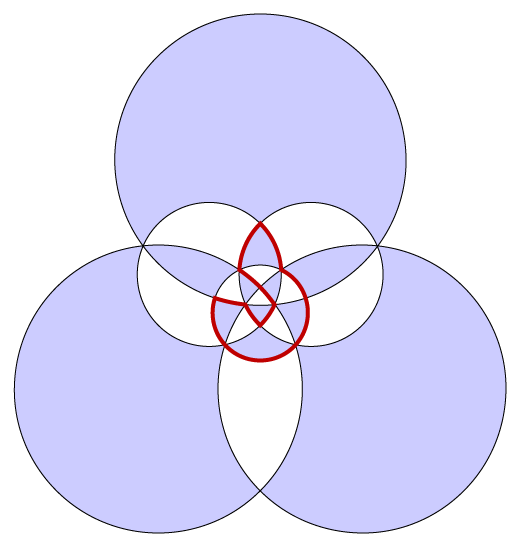

The key building blocks for our classification are a more restricted class of orthogonal polyhedra: ones that, like the permutohedron above, can be viewed from a point of view from which only a single vertex is hidden behind the other faces. As we show, a planar graph forms the set of vertices and edges of a simple orthogonal polyhedron with one hidden vertex if and only if its dual graph has a structure like the one in the drawing below: a cycle or set of cycles that passes through each interior vertex and that uses exactly one edge from every white interior triangle. Geometrically, the cycles separate the mountain folds from the valley folds of the polyhedron. If the dual graph is 4-connected, then it always has a cycle cover of this type, and the other polyhedra of our classification can be constructed by gluing together polyhedra for dual-4-connected subgraphs.

In my previous paper on bendless orthogonal drawing, I showed how to represent the permutohedron (and many other graphs) as a system of axis-parallel line segments in 3d, so that three mutually perpendicular line segments meet at each vertex. But in that paper, the line segments were allowed to cross each other, and the drawings I found were in general very far from being polyhedral. One of the results in the new paper is that, whenever a planar graph has a bendless drawing of this type, then it is the graph of a polyhedron: all crossings and other forms of self-intersections can be eliminated.

Coincidentally, today's arXiv papers also include another one related to Steinitz's theorem (the real one, about convex polyhedra): On the number of spanning trees a planar graph can have (arXiv:0912.0712) by Kevin Buchin and André Schulz. Buchin and Schulz show that, in order to realize a 3d convex polyhedron using integer coordinates, one needs only \( O(n) \) bits per coordinate, improving an exponential bound from Steinitz' original paper and several other previous polynomial bounds.

Comments:

2009-12-04T03:09:58Z

i am curious about how you practically think about those problems. lots of paper and pencil scribbling? some software tools? big blackboards?

2009-12-04T03:26:10Z

Big whiteboards, lots of pencil and paper sketches (I've started carrying around one of those little squared Moleskine pocket notebooks, and I used it a lot for this), lots of examples, and lots of email back and forth. Not much in the way of software tools except drawing programs. We did a little of this in wave rather than email, but that was only in the last week or two of writing up the paper, after we already had most of it worked out and written.

2009-12-04T03:37:41Z

i inherited from my master Maurice Nivat, who had a deep polyominoes habit, the taste for those: http://store.americanapparel.net/rhodia16.html

2009-12-04T03:46:46Z

The Moleskine ones have some other features I like (fits in a jeans pocket, hard cover on both sides with a built-in elastic band to hold it closed) but that one looks like a good alternative.