Flat equilateral tori?

A flat torus is a surface topologically equivalent to a torus such that any point has a neighborhood that (in terms of the intrinsic metric of the surface) looks locally like a flat plane. Standard examples are the square and hexagonal torus in which the opposite edges of a square or hexagon are glued together. The square torus has a nice smooth embedding in four dimensions as the Cartesian product of two circles in perpendicular planes (the “Clifford torus”) but it seems difficult to embed in 3d: one can get a smooth cylinder by gluing one pair of edges but then to get the remaining two boundaries to meet each other it seems some crumpling is necessary. Perhaps surprisingly, with enough crumpling, it really can be embedded in 3d, within arbitrarily small volumes: this is the 2-dimensional case of the Nash–Kuiper theorem.

So if a 3d flat torus can't be smooth, how nice can it be? Maybe a polyhedron that, like the regular polyhedra and the Johnson solids, has only regular faces? This is the idea behind a question asked in 1997 by Nick Halloway: is it possible to form a polyhedral torus in which all faces are equilateral triangles and all vertices have degree six? It seems on the face of it that the answer should be no: if there are n vertices, there are 3n degrees of freedom for where they can be, matched by 3n distance constraints, leaving zero degrees of freedom, but any object that can actually be constructed in space has six degrees of freedom for its position and rotation. However, this is not a proof, because some of the distance constraints might be redundant and not reduce the degrees of freedom.

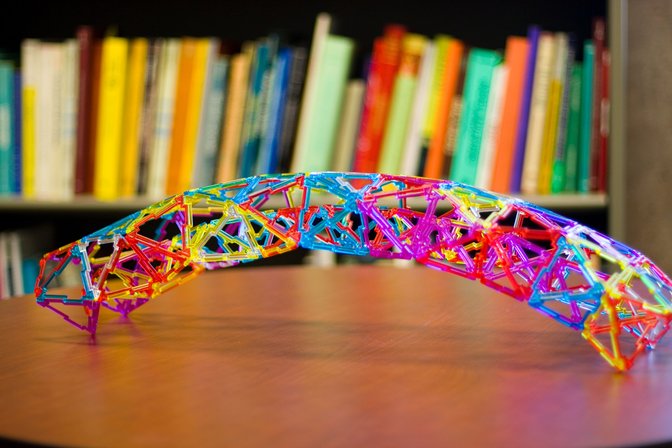

Undeterred, I tried playing with some physical equilateral triangles (from the geofix construction system), and built a structure that seems like it might work.

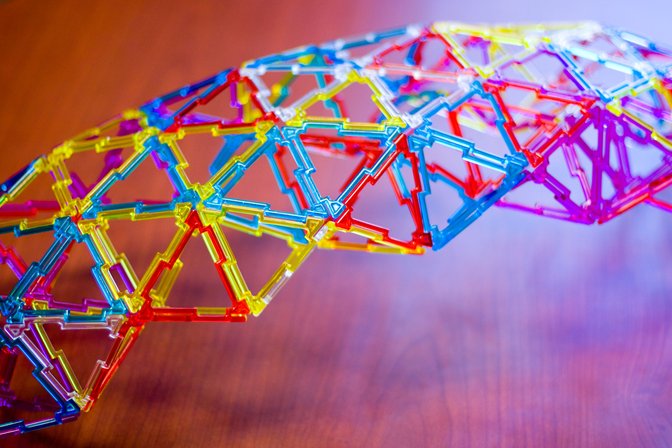

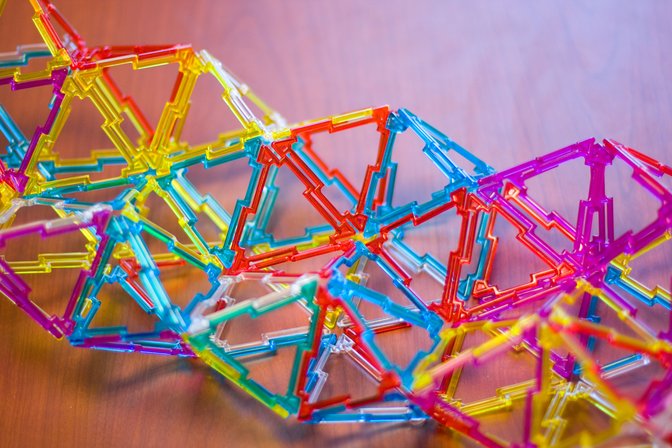

It consists of a sequence of hexagonal antiprisms glued together end-to-end and crumpled so that the triangular faces are still equilateral but the hexagonal faces become nonplanar and nonconvex. With the right crumpling pattern, the crumpled antiprism attaches to a mirror image of itself to form a unit with a nonzero bending angle.

Repeating the process forms an arched structure that feels quite rigid and seems like it could be completed to form a torus.

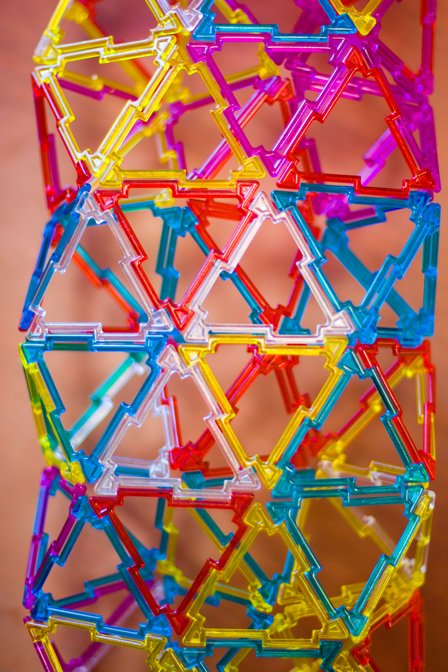

The outer surface of the arch has a zigzag path of triangles in which all dihedral angles are convex. Two more triangles inside each turn of the path form together with four triangles of the path a hexagon that is only very slightly nonconvex. However, the inside of the arch has a much more crumpled repeating pattern, shown below.

(I've included a few more photos of this construction at my web photo gallery.)

Of course, being able to build it out of plastic units is not a mathematical proof: there's enough give in the units that it would be possible to build a structure like this even if it did not quite work mathematically, like the near-miss Johnson solids. So rather than answering Halloway's question, this only gives rise to more questions: Is the arch I constructed a model of an actual mathematical surface with equilateral triangle faces and degree-six vertices? (My guess: yes.) Is this surface rigid, with its only degrees of freedom being the ability to flex the triangles near the unfinished ends of the arch? (My guess: yes.) Is the turning angle per unit of the arch an integer fraction of 2π, so that by adding enough units one can form a torus that connects back to itself to form a flat torus? (My guess: no — that seems too big a coincidence to hope for.) Is there some other repeating unit built from larger numbers of equilateral triangles that does have an integer-fraction turning angle and does form a complete torus? (My guess: again no — there should be a countable number of these units, their turning angles are arbitrary real numbers, and there's no reason for these numbers to coincide with unit fractions, but this seems like it would be difficult to prove.)

Probably an easier question: suppose we give up on equilateral triangles, and just ask for a polyhedral flat torus in which the faces are triangles of arbitrary shapes. How few triangles are needed?

Comments:

2009-02-08T11:24:23Z

Very intersting. Any chance of an image of a single unit in isolation?

2009-02-08T16:22:54Z

You can see a single unit in a different configuration in http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hexagonal_antiprism.png

Or did you mean showing it in the right geometric position? They're very floppy until several of them are attached together but I suppose it might be possible to get it into approximately the right shape.

2009-02-08T17:42:26Z

Yes, I meant the crumpled unit. I'm trying to reconstruct your work using Geo-mag, and it would be very useful to see an individual collapsed anti-prism isolated, but I certainly see what you mean - very floppy indeed.

2009-03-12T23:32:06Z

This reminds me of something I found when modeling origami structures in CAD. I folded a pattern from regular squares and their diagonals which could collapse so that the edges formed equilateral triangles. It is the second pattern in this image:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/32q2/3343503879/

At first I thought the slight curvature of the model was just due to thickness of the paper or inaccuracy, but when I modeled it on the computer, I was surprised to find the curvature was real and the structure formed a cylinder a little over 18 triangles around. I thought there might also be some relation to this strange near fit of tetrahedra:

http://spacesymmetrystructure.wordpress.com/2007/07/20/an-unexpected-gap/

2009-03-12T23:41:06Z

There's some interesting related work by Ron Resch on bendable origami structures. I have a file at http://www.ics.uci.edu/~eppstein/junkyard/resch.pdf of one of his folding patterns — it folds to form a surface of equilateral triangles with gussets between them that is quite flexible.

2009-03-13T16:59:03Z

Ah! I knew your name was familiar, but hadn't made the connection to the geometry junkyard. That site has been a source of inspiration on so many occasions - thanks! I know the work of Ron Resch (probably through your site come to think of it) and the page I tried to link to above shows his pattern plus some related ones of my own. Im not sure, but I think that although all the faces are obviously flat when fully folded or fully unfolded most of these rely on a very slight warping of the paper to go between them.

2009-03-13T21:24:19Z

Sorry, you need to have an actual livejournal account to make html links that work.

Yes, the question of whether these things can be folded mathematically or only physically is also an interesting one.