Cartograms that can morph

In recent years on the web we've seen a lot of information visualizations in the form of cartograms, illustrations that resemble maps in that they show regions of the earth but that differ from maps in that the shapes, positions, and adjacencies of these regions are distorted so that their areas represent some non-geographic data to be visualized. A familiar example is the stretched maps of the United States showing the numbers of electoral college votes associated with each state; populous states such as New York and California become larger in these maps while sparsely populated states such as those in the great plains are relatively shrunken.

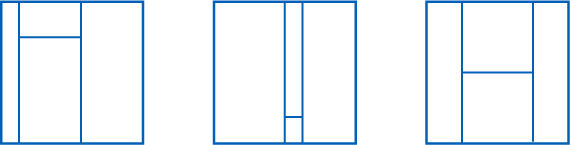

Although seemingly modern, this kind of visualization goes back at least to a 1934 paper of Erwin Raisz in Geographical Review. Raisz proposed the idea of stylizing the regions of a cartogram by drawing them as rectangles, not just as a way to make drawing the cartogram easier and to make the visual comparison of areas less error-prone, but also as a way to remind readers that cartograms are not maps. Imagine, for instance, that the four regions in the following illustration represent the pacific west of the United States on the left, the great plains and midwest on top, the south on the bottom, and the eastern seabord on the right.

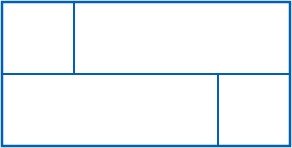

These three rectangular cartograms of the same four regions could represent three different numerical quantities associated with each region. The partition of a rectangle into four smaller rectangles shown above has a property that makes it very useful for cartograms: no matter what four numbers one supplies for the areas of the four smaller rectangles, there is a way of drawing a cartogram with those specified areas using rectangles with the same adjacency pattern and the same relative positions. Even more, it is possible to continuously morph each of the drawings into each other. We say that this layout is area-universal. In contrast the layout below (which has the same pattern of adjacencies, but not the same position of regions, as the ones above) is not area-universal: the illustration depicts an assignment of areas 1,3,3,1 to the rectangles but it is not possible to give them areas 3,1,1,3 without changing their positions or adjacencies.

The new preprint “Area-Universal Rectangular Layouts” that I mentioned in my previous post looks at the problem of characterizing and finding layouts with this area-universal property. Along with the cartogram application, we think this should be useful for VLSI design (where the rectangles in a layout represent subunits of a computer chip), treemap visualization (the outer rectangle representing a node in a tree and the inner rectangles representing its children), architectural design (where the rectangles represent rooms of varying sizes), and graph drawing (with the rectangles representing vertices and their adjacencies representing edges).

One of the key ideas in the preprint, described in more detail in my previous post, is to use the Birkhoff representation theorem to simplify the search for layouts having the properties we desire. Another important idea is to generalize the concept of equivalence of layouts. Two layouts are equivalent, as described above, if they have the same adjacencies of rectangles with the same relative positions (if a pair of adjacent rectangles are to the left and right of each other in one layout they should be in the other layout as well). Two layouts are order-equivalent if they have the same incidence relationships between line segments and rectangles. The incidences between vertical line segments and rectangles can be represented as a planar graph with a node per line segment and an edge connecting the segments on the left and right sides of each rectangle, and the incidences between horizontal line segments and rectangles can be represented by the dual of this graph, so order-equivalence can be thought of as a kind of planar graph isomorphism.

Equivalence implies order-equivalence but not vice versa. For example, the non-universal layout in the second figure above is order-equivalent to, but not equivalent to, its left-right mirror reversal. As this example shows, in order-equivalence, tee junctions such as those on the midline of the layout are allowed to slide past each other. But that's the only thing that can go wrong: if all tee-junctions interior to each line segment of the layout extend in the same direction (as happens in the first figure) then order-equivalence and equivalence are the same relation. We call a layout with this property one-sided, because the tee junctions on each segment only extend to one side of the segment.

In our paper, we show that for any layout, and any new assignment of areas, there exists a unique order-equivalent layout with the given areas. The proof of uniqueness uses an idea reminiscent of Sperner's lemma to show that in any two different order-equivalent layouts with the same bounding box, some rectangle must be strictly larger in one layout than another; the proof of existence uses uniqueness and the inverse function theorem to find a morph to a layout with the desired areas. It follows from this uniqueness theorem that the area-universal layouts are exactly the one-sided ones; we then use Birkhoff's theorem (as described in the previous post) to devise algorithms for constructing one-sided layouts.

Comments:

2009-01-29T16:34:00Z

I'm excited to see an application to Dasher layouts; the existing layout algorithms seem very clumsy.

2009-01-29T16:39:55Z

I assume you mean the Dasher mouse text-entry system? I hadn't seen it before but it also uses rectangles of differing areas as regions to click into to get different letters, if I'm understanding the Wikipedia article correctly.

2009-01-29T16:50:07Z

I'm surprised you're not familiar with it - it's a great application of information theory. The area of the rectangles (or maybe the longest dimension, I forget) is proportional to the probability that the predictor algorithm (for example, a markov model of your writing) assigns to that character.

2009-01-30T13:25:53Z

Interesting! Being more of a practitioner and less of a theorist, what useful applications to treemap visualization layouts do you see? Less disruptive relayouts of treemaps, that retain node positions under size updates better? Would any of this have any application to the type of non-spacefilling rectangular cartograms that Panse has written about in his dissertation and possible in a paper named something like RecMap, I think.

2009-01-30T13:40:17Z

Specifically we were looking at a paper of Jack van Wijk (cited in the new paper) that was trying to control the aspect ratio of the rectangles in a treemap by using alternative layouts for the children of each node. So rather than answer your question directly maybe I should just point you at that paper: http://www.win.tue.nl/~vanwijk/stm.pdf

The advantage of using an area-universal layout in this context would show up most clearly if the treemap is morphing (e.g. the underlying tree is changing or some sort of point-of-view weighting is being used), as an area-universal layout could do this without changing the mental map.

2009-02-03T08:51:35Z

Very interesting. I am well aware of Jarke van Wijks paper. And since stable(r) nodes positions in any layout that changes over time are extremely helpful to user perception, it seems the fundamental problem with the treemap squarified (re)layout, ie disruptive (node position) changes could be addressed?

I think one of the reasons that the squarified layout is often used in treemaps is that is scales pretty well. Do you see area-universal layouts scaling as well, running in "interactive time" for example when laying out a 100.000 node tree?

2009-02-03T16:05:39Z

One would have to use a repetitive layout that's easy to work with rather than an arbitrary area-universal layout, I think. But there are repetitive area-universal layouts such as a basketweave pattern

So I'm not so worried about computation time, but I guess one question is whether the greater irregularity of an area-universal layout is too much of a price to pay for their greater stability.