3-coloring and xyz graphs

It turns out there's a very simple characterization of xyz graphs: if a graph G is embedded on a surface, then that embedding can be represented as an xyz graph, with the surface represented via the flat polygons of the xyz graph, if and only if: (1) every face of the embedding is a disk without repeated vertices, (2) if any two faces intersect, they do so in an edge, and (3) the faces can be 3-colored.

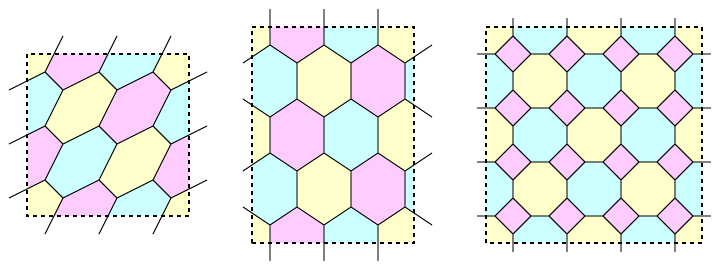

For instance, the following three tori (drawn as rectangles with periodic boundary conditions) all form xyz graphs. The left one is the nine-hexagon torus we've already seen before, center is another twelve-hexagon torus, and right is a torus embedding of the four-dimensional cube-connected-cycles network (and also a GEM for K4,4).

To prove this characterization, in one direction, the coloring is given by the partition of the faces of an xyz graph into three parallel families; in the other direction we can assign each face an index number, and use the indexes of the adjacent faces of each color as the coordinates of the vertices similarly to the xyz representation of GEMs noted before. The requirement that the graph be 3-regular follows from property (2) above.

Testing these conditions for embedded graphs can be done easily in linear time: color three faces at a vertex, propagate colors at any vertex with two colored faces, and check whether this results in a valid coloring of the whole surface. Of course, if we are just given a graph, finding the correct surface to embed it into may be harder...

It has long been known that a maximal planar graph is 3-chromatic if and only if it is Eulerian [Heawood 1898]; dually, the faces of a 3-regular planar subdivision can be 3-colored if and only if they all have evenly many sides. So every simple convex polyhedron in which all faces have evenly many sides forms an xyz graph. In particular, all planar cubic partial cubes are xyz graphs.

Comments:

2006-06-12T03:42:02Z

I havn't been following too closely, but I want to make sure I have my terminology right... every face having no repeated vertices is the same as no bridges, yes?

2006-06-12T03:57:59Z

For planar graphs that's close to it, though an articulation point would also lead to a repeated vertex. For graphs on nonplanar surfaces it's possible for a tunnel to cause a face to include the same vertex more than once without a bridge or articulation point, though.

2006-06-12T19:23:54Z

An articulation point is, I'm guessing, like this

o o / \ / \ o X o \ / \ / o oAlso known as a cut vertex?

I'll have to think about what a tunnel could mean.

2006-06-12T20:40:48Z

Also known as a cut vertex?

Yes.

I'll have to think about what a tunnel could mean.

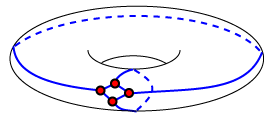

Ok, here's an example. Draw a cycle of four vertices on a torus, smaller than the radius of the torus, then connect opposite pairs of points by edges that go all the way around the torus, once in the short direction and once in the long direction, as in this sloppy sketch:

This drawing has four vertices, six edges, but only two faces: one is the small quadrilateral, and everything else is in a single large face since you can get from any point outside the quadrilateral to any other such point without crossing an edge of the drawing. If you walk around the boundary of the large face, it looks like an octagon, but each of the vertices and each of the edges appears twice in that walk. However the graph is 3-connected (it is just the complete graph on four vertices).