Celtix is NP-complete

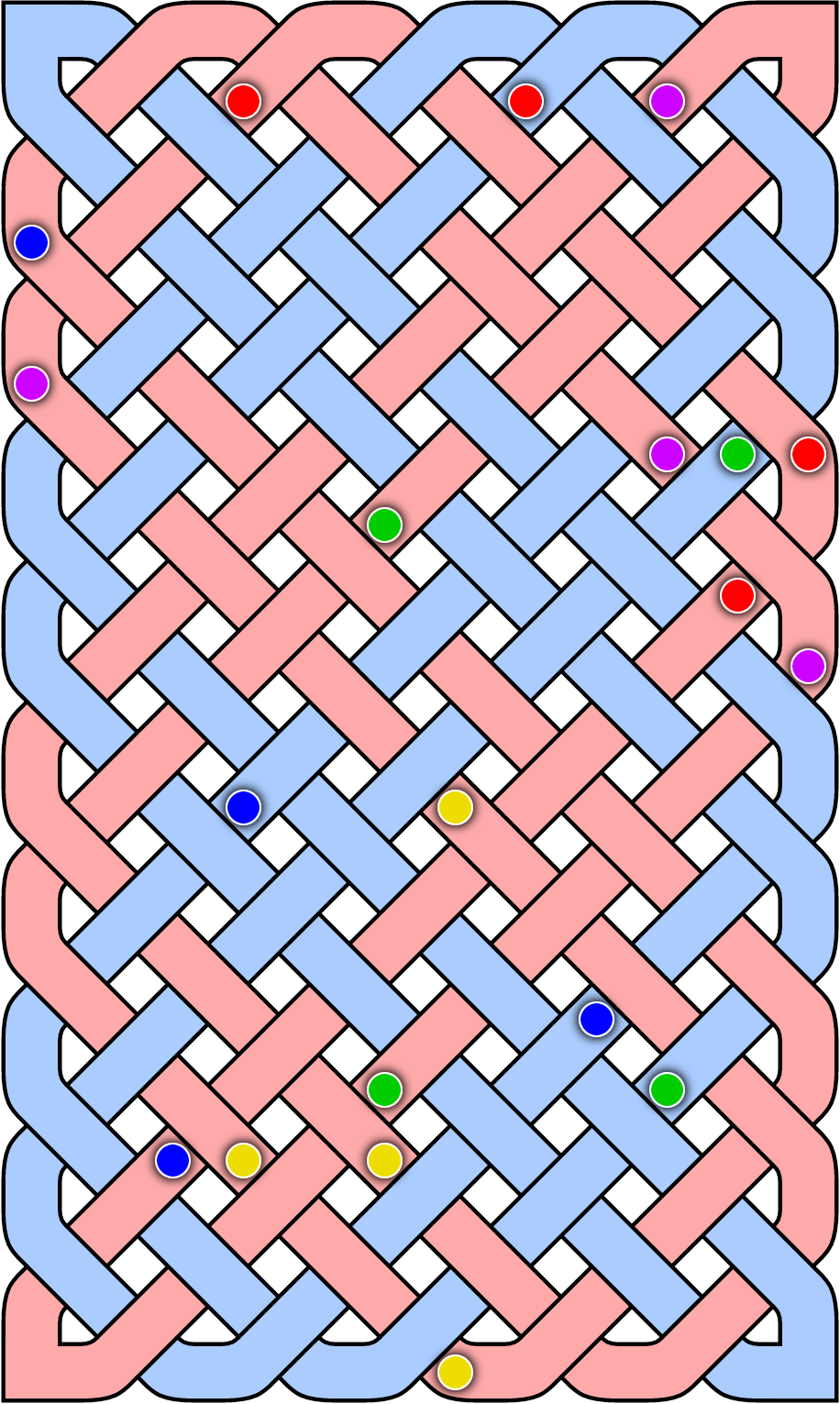

Celtix is a puzzle recently developed by Andrew Taylor, in which one is given a rectangular array filled with thick diagonal lines that reflect off the walls of the rectangle to form a criss-crossing knotted pattern.

Some points inside the rectangle are colored (four points of each of five colors), and the goal is to add reflecting walls at some of the internal crossing points so that the thick lines form five loops, one of each color.

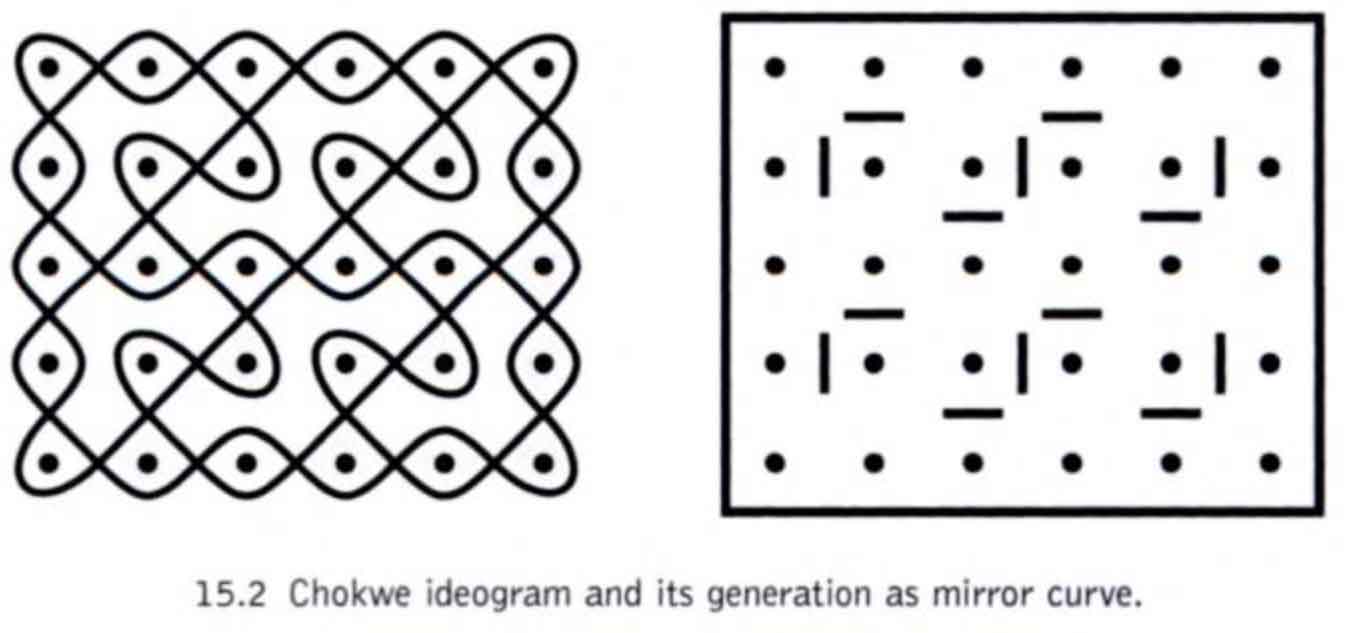

Although Celtix was inspired by and named after Celtic knotwork, which it resembles, very similar ideas of placing internal reflecting walls at the diagonal crossing points within a rectangle have also been studied in connection with the sona or lusona patterns from the Chokwe people of Angola recorded by ethnomathematician Paulus Gerdes, where the goal is to place the mirrors to produce a single loop. See for instance Gerdes’ “Lunda symmetry: Where geometry meets art”, in The Visual Mind II (2005), from which the image below is a clipping.

The Celtix puzzle encourages you to minimize the number of added walls, by keeping track of your minimum so far and providing features to share your low score on social media. But an interesting variation seeks instead the maximum number of walls.

Maximizing walls turns out to be equivalent to minimizing two-colored crossings, because those are the only kinds of crossings that cannot be eliminated by adding a wall. For any crossing between two parts of the same loop, of a single color, only one of the two ways of adding a wall can break the loop into two, so the other wall is always available to add. For this reason, the maximum number of walls is always an even number: there are an even number of positions where walls can be placed, and an even number of positions where pairs of loops cross in the optimal solution, so an even number of remaining positions where walls are placed.

I think everyone expects it to be \(\mathsf{NP}\)-complete to determine whether a Celtix puzzle has a solution (in some generalized form with larger rectangles and maybe also more colors or more clues per color). This post sketches a proof. It is simpler to begin with an outlined proof of hardness for the following wall-maximizing variation: It is \(\mathsf{NP}\)-complete to determine whether a Celtix puzzle has a solution with every position replaced by a wall, so that there are no crossings (and in particular no two-colored crossings), with four clues per color, rectangles of unbounded size, and an unbounded number of colors.

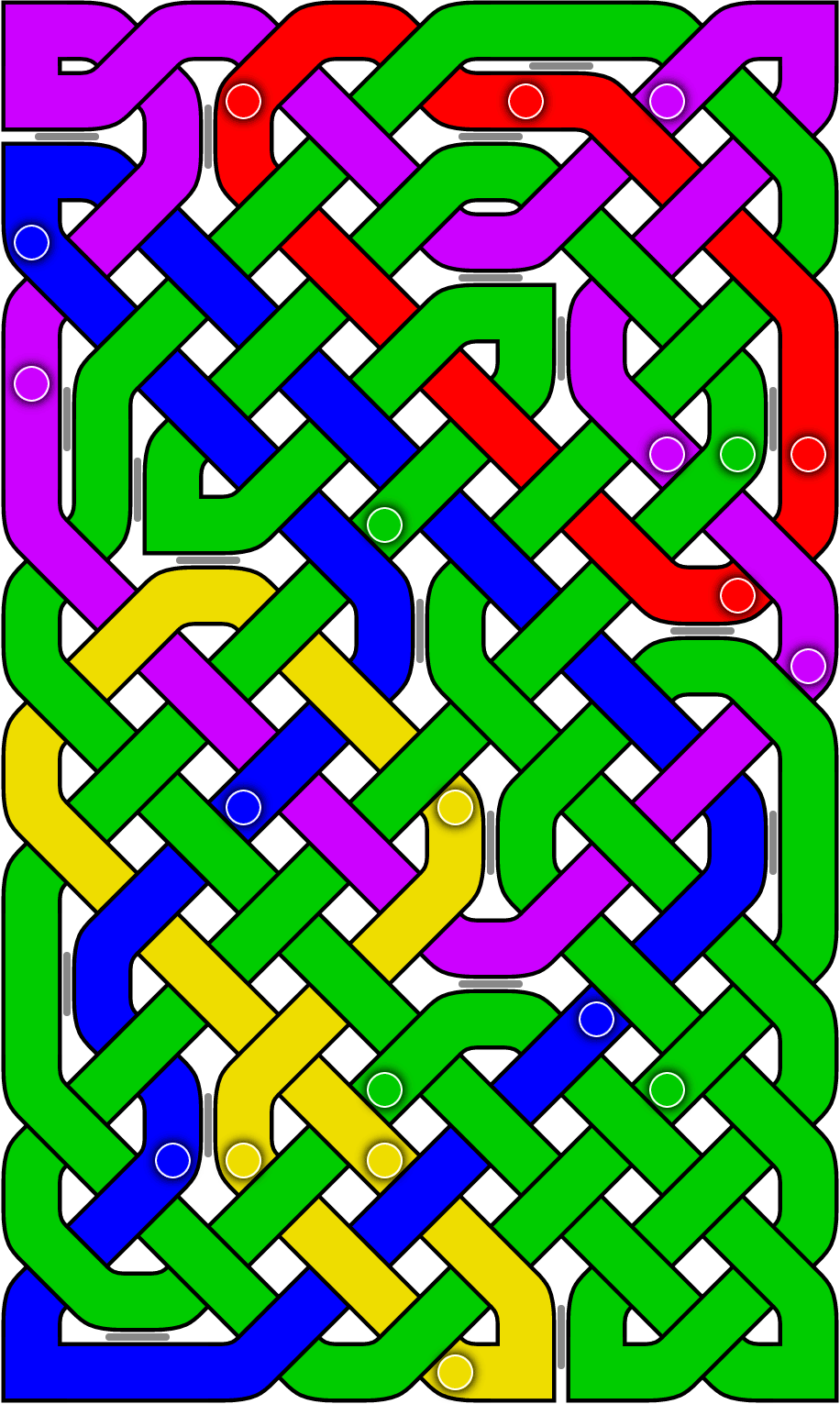

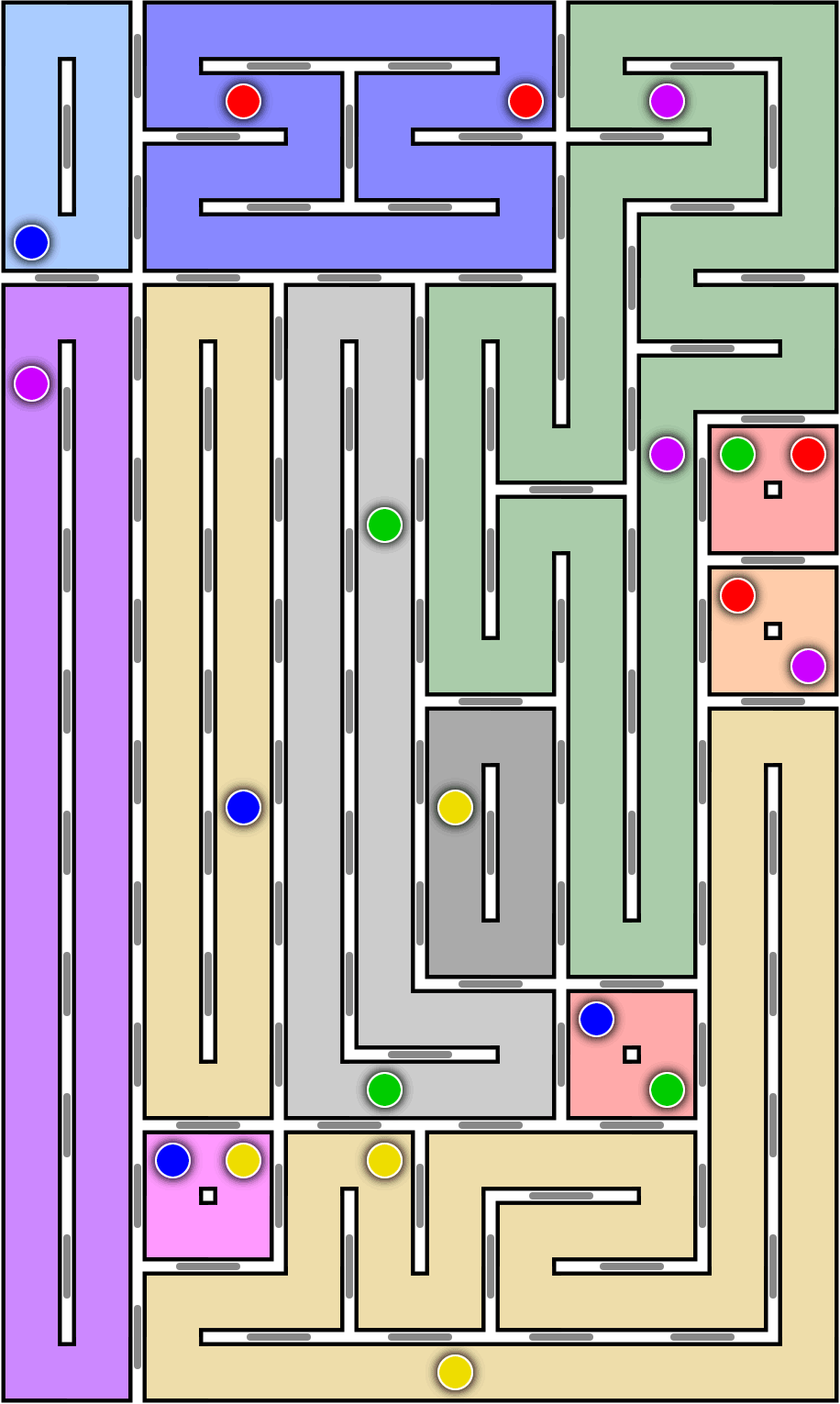

The proof uses the observation that, if you place walls everywhere, the rectangle can be partitioned into \(2\times 2\) blocks of color, among which the only choice is which subsets of blocks to group together into connected components. In the example below, some of those \(2\times 2\) blocks have clues of two different colors, showing that an all-wall solution is immediately impossible. Except for that problem, I have grouped some of the \(2\times 2\) blocks into larger monochromatic polyominoes (not optimally). If this were the only thing that could happen, the all-wall Celtix problem could be rephrased as: in a grid of squares with some squares colored, can we group the squares into polyominoes with a single polyomino per color?

But now this is almost like the Numberlink puzzle of filling a grid by paths connecting pairs of numbers, proven \(\mathsf{NP}\)-complete by Kotsuma and Takenaga in 2010 and in a more general form by Adcock et al. in 2014. It even more closely resembles a problem proven hard by James F. Lynch in 1975 and used as the basis of the proof by Adcock et al. Lynch showed that it is hard to connect a given collection of pairs of squares in a rectangular grid by disjoint paths through the other squares, avoiding certain obstacle squares. To convert this to all-wall Celtix, take a hard instance of Lynch’s problem, expand each of Lynch’s grid squares into a \(2\times 2\) Celtix block, choose a distinct color for each pair of squares to be connected, and place a clue of that color in each corresponding Celtix block. Additionally, use clues of a distinct color within each obstacle block. If Lynch’s problem instance has a solution, its paths can be expanded to polyominoes, and unused blocks can be attached to neighboring loops, to form a solution of the all-wall Celtix problem. And if the all-wall Celtix problem has a solution, each polyomino contains a path disjoint from the paths within the other polyominos, solving Lynch’s problem. Since Lynch’s problem is \(\mathsf{NP}\)-complete, so is \(2\times 2\) block Celtix.

But \(2\times 2\) block Celtix isn’t quite the same as all-wall Celtix, because of another complication I didn’t mention yet: It is possible for one loop to surround another, and inside the outer loop the arrangement of \(2\times 2\) blocks is offset by one.

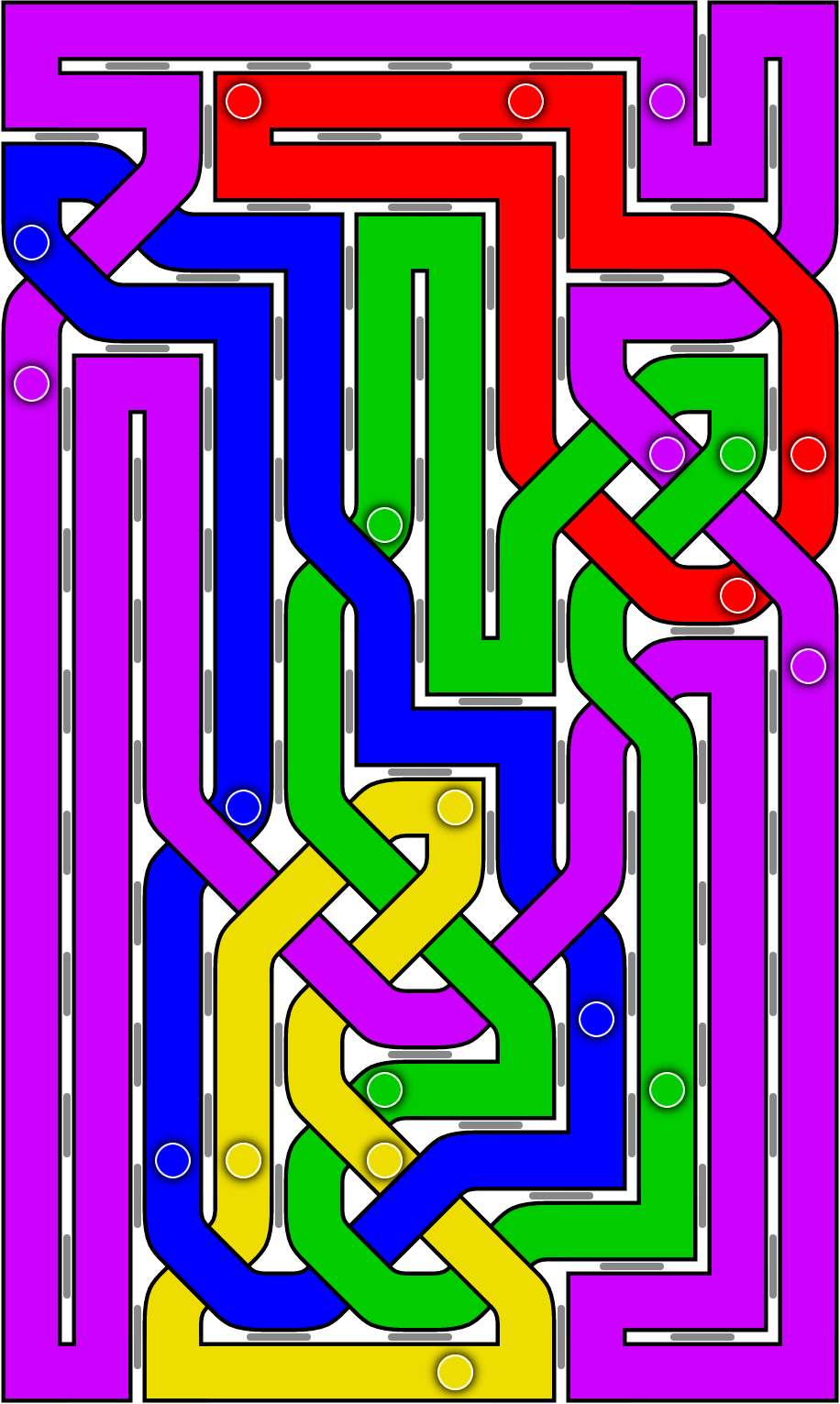

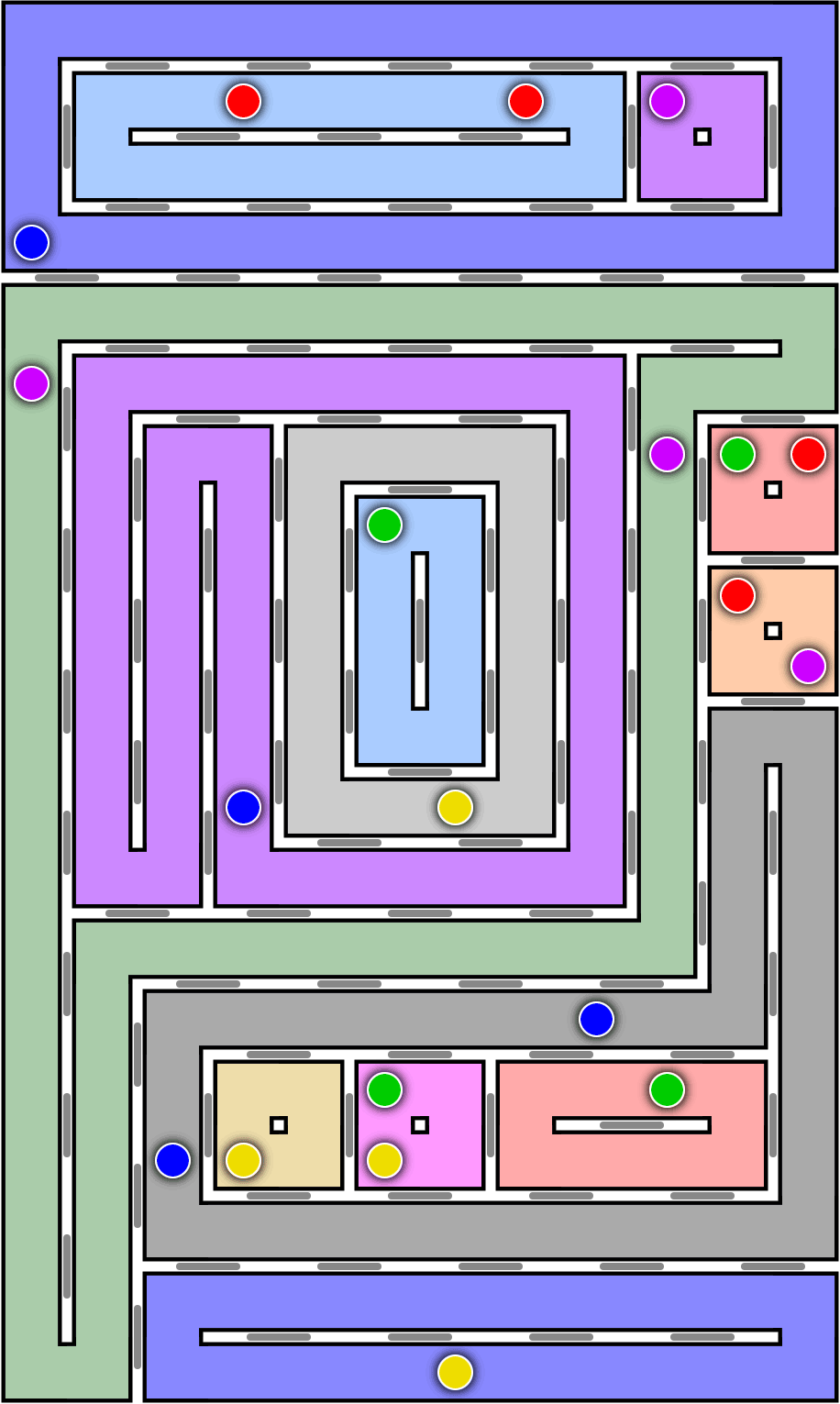

To prove hardness of Celtix, without artificially imposing the restriction of using \(2\times 2\) blocks, we will need to avoid these enclosing loops. And to do so, it helps to look more closely at Lynch’s \(\mathsf{NP}\)-completeness proof. As Lynch describes it, the construction is not really a set of labeled pairs of squares in a rectangular grid of squares. Instead, it looks like a wiring diagram, consisting of horizontal and vertical line segments, like the streets of a regular grid of streets, meeting at right angles, three-way junctions, and four-way junctions. The clauses are represented by pairs of junctions at the top and the bottom of the diagram that must be connected by a more-or-less-vertical path. Each vertex is represented by a horizontally arranged sequence of pairs of junctions to be connected, ordered like AbA CbdC EdfE … and connected by wires allowing only two patterns of connections. The capital letters can be connected above the lowercase ones, representing a true value of the variable, or below, representing a false value. Lynch then provides gadgets that allow a clause path to pass through a variable regardless of its truth assignment (the top half of the figure below) or to be able to pass only for one of the truth assignments (bottom half). Lynch arranges the variables and clauses so that they all cross each other, with three paths per clause, each of which requires one of the variables to be set in a certain way (the way that would satisfy that clause). In this way, Lynch constructs a reduction from 3-satisfiability to his grid path problem.

(I’m a little worried that as I drew them the variables can sneak through unused clause paths and flip their values, but that can be patched by replacing each path used for the variables by a thickened set of multiple paths, so that there isn’t enough bandwidth to sneak all of them through.)

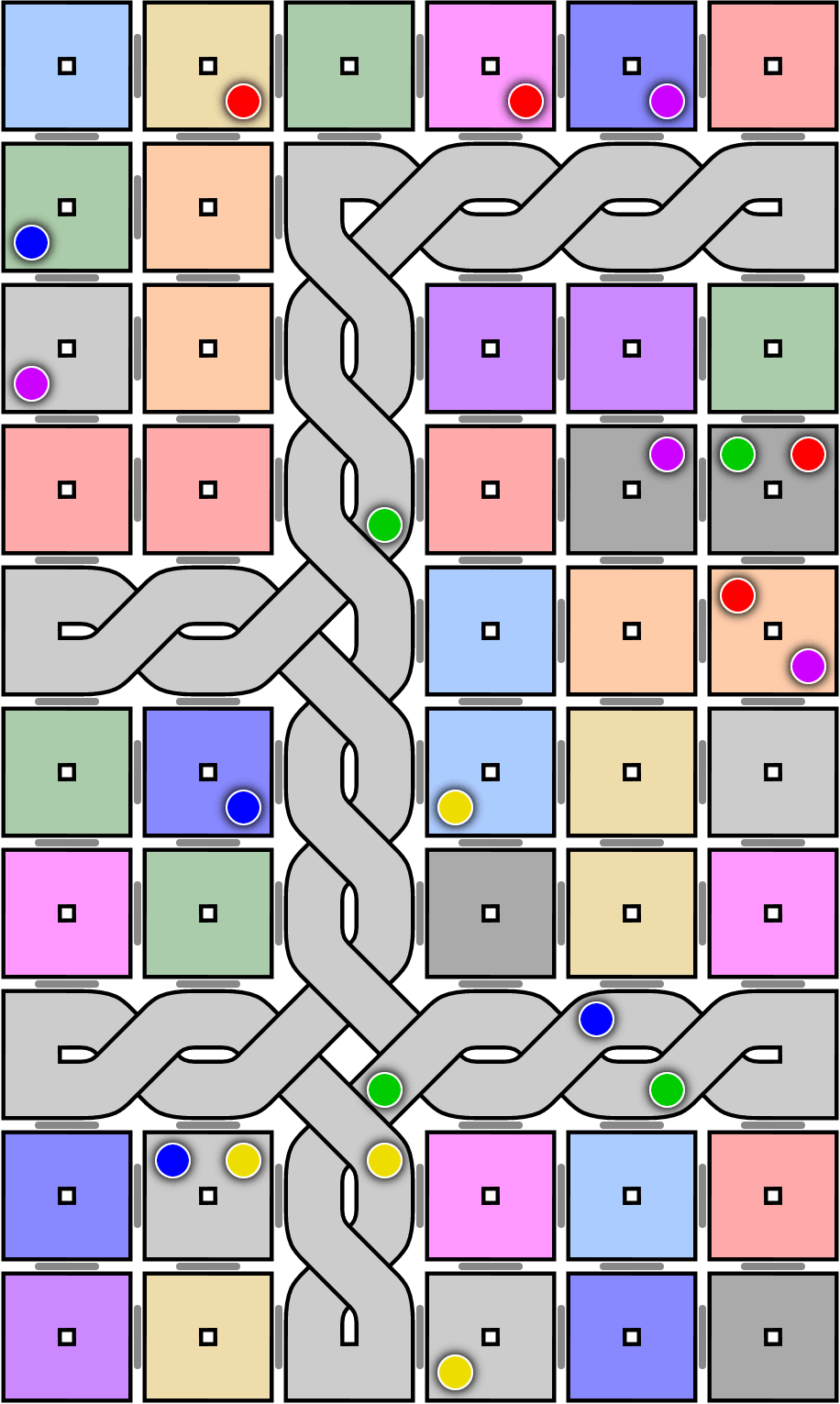

There is a lot of space between all these wires that, when translated into Celtix, turns into little loops that each occupy a single \(2\times 2\) block. For instance, here’s a small wiring diagram with a right turn (top), a three-way junction (middle), and a four-way junction (bottom), where to make it more visually apparent I have drawn the wires as twisted pairs rather than polyominoes.

If we add four clues to each of those blocks in the open space, they will be forced to be blocks in the solution. It will not be possible to surround them by a single-stranded Celtix loop, because that would disrupt their block structure. It is still possible for two loops of different colors to collide head-on at a four-way junction and then spread in both directions away from the junction, but to prevent this possibility we can simply expand each four-way junction into two three-way junctions. After this step, the translation from Lynch’s diagram to Celtix can only be solved as Lynch intended, by double-stranded paths through the wires of his diagram. Any parts of wires unused by these paths can be filled by connecting them to nearby loops.

So, based on this reduction: solvability of Celtix puzzles is \(\mathsf{NP}\)-complete, and it remains \(\mathsf{NP}\)-complete for puzzles that (if solvable) have a crossing-free solution.