Flat folding and map folding

Another day, another new arXiv preprint. Today’s is “A parameterized algorithm for flat folding” (arXiv:2306.11939, to appear at CCCG 2023), a paper I mentioned in the last slide of my recent talk on graph width parameters for parameterized geometric algorithms.

It’s been known since the work of Marshall Bern and Barry Hayes in SODA 1996 that it’s NP-complete to test whether a given origami pattern (with or without an assignment of a mountain or valley fold to each crease) can be folded flat. Of course, many origami structures are not intended to be flat, but they still often start with a flat base, and testing flatness is a prerequisite for any more complicated foldability question you might have. On the other hand, if a pattern does fold flat, it’s very easy to determine where in plane each piece of paper folds to; the hard part is determining the above-below relation between different pieces of paper that fold to the same points.

The new paper defines a graph from any folding pattern, whose vertices represent connected regions of the plane that should be covered by the same pieces of paper in the folded state and whose edges represent adjacencies between those regions. An example is shown below.

The left side is the folding pattern (blue for valley folds and red for mountain folds): first, fold the right edge of the paper on top of the rest, along the vertical blue crease, and then second, fold the top right corner down, along the two diagonal creases. The right side is how it should map to a folded state (without an assignment of an above-below relation to the layers in that state) and the resulting graph. The goal of the algorithm is to figure out that the regions of the folding pattern should be layered (bottom to top) in the order: big pentagon, lower right trapezoid, upper right trapezoid, triangle. It determines whether a folded state like that exists, but not the sequence of moves you would need to make to get there. But some care is needed in defining the layer order: it has to be local, because there exist folding patterns where different regions are layered differently in different parts of the folded state.

The paper shows that finding a valid above-below relation for each region can be done using a dynamic programming algorithm in time exponential in the treewidth of this graph, where the base of the exponential is factorial in the ply of the folding pattern, the maximum number of pieces of paper that all fold on top of each other at any single point. As it also shows, even for patterns of bounded ply, the exponential dependence on treewidth is necessary under standard complexity-theoretic assumptions.

But what about the dependence on ply? Is that necessary? Why should it be difficult to fold patterns that have many layers, but simple region adjacency graphs?

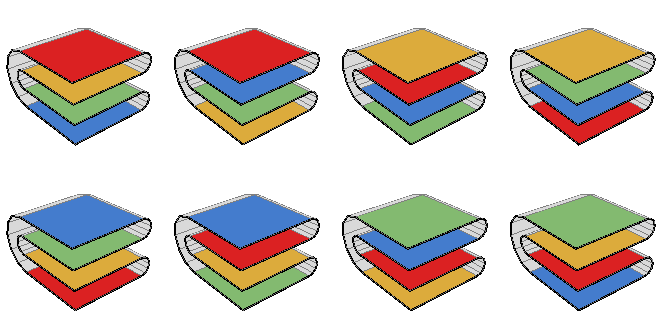

Unlike for treewidth, I don’t have a proof that high ply makes the problem hard. But there is a natural class of problems for which the ply is very high, the treewidth is tiny, and the complexity of finding a flat folding is a famous open problem. This is the map folding problem, where the input is just a rectangular grid with labeled creases, and the desired output is a flat-folded state respecting the given labeling. Its region adjacency graph is just a single vertex (everything should fold onto a single square), but its ply can be big (the number of squares in the entire grid). Even for a very simple case, a \(2\times 2\) grid, Wikipedia provides the following illustration of the many vertical orderings among the squares of the grid that are possible. Each square is shown with a different color, visible on both of its sides:

The \(1\times n\) map folding problem is easy: just fold over one square from the end of a strip of \(n\) squares, according to the label of its crease, and then solve the remaining \(1\times (n-1)\) problem recursively, treating the folded-over square and the next square that it is folded onto as a single unit. In a 2012 MIT master’s thesis supervised by Erik Demaine, Thomas Morgan announced a solution to the \(2\times n\) map folding problem, although I don’t know that it was ever published in any other form. The algorithm is complicated, with time bound \(O(n^9)\), and the writing is not always clear.

The techniques from Morgan’s thesis are very specific to the \(2\times n\) case. Basically, everything you need to know can be recovered from a one-dimensional flat folding of the central crease of the \(2\times n\) grid. At the end of the thesis there is a single paragraph on higher order grids, which (after removing unnecessary complications) boils down to testing all orderings of the squares that are consistent with the above-below relations forced by the crease labels of adjacent squares. The number of orderings can be very small (for instance, if you accordion-fold in one direction and then the other, there is only one consistent ordering) and when it is the algorithm is fast. Beyond that observation, the map folding problem for grids larger than \(2\times n\) appears to be wide open.