Reflections in an octagonal mirror maze

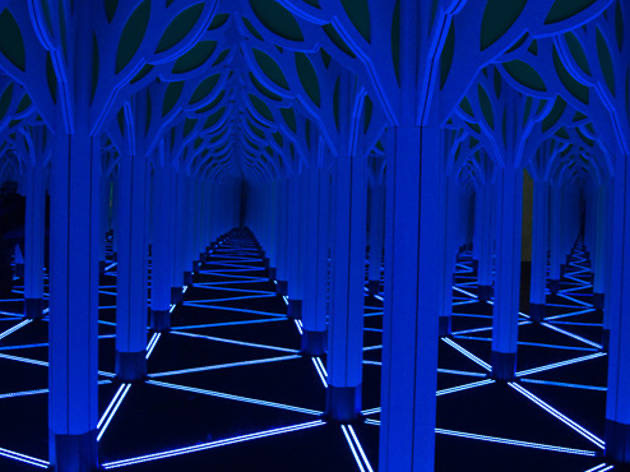

The second preprint from my CCCG papers is now online. It is “Reflections in an octagonal mirror maze”, arXiv:2206.11413. The title is quite literal: suppose you find yourself in a mirror maze, where the mirrors are aligned with the sides of an octagon, and have integer coordinates (meaning that, on a floorplan of the maze, the mirrors become line segments between points of an integer grid). What would you see if you looked in any given direction? It might be many reflections eventually leading to the back of your own head, to the exit, or some other non-reflective part of the maze. The example below, from the Museum of Science & Industry in Chicago, is hexagonal rather than octagonal, but otherwise has much the same effect:

In this example, it looks like you might be seeing something else, not the exit or your own head: a corridor of infinitely many reflections. But when looking in a direction of rational slope, and without tricks involving one-way mirrors (my guess at what’s happening in the photo), that’s not actually possible. Rationality implies that there are only finitely many possible points where your view could hit a mirror: in the photo above, all the reflections down the corridor look like they are actually on the center lines of the mirrors. Because there are only finitely many of these points (in reality, if not in what you see), such a view would have to eventually repeat, in a finite cycle. And finite cycles like that are definitely possible, but you can’t see them, because putting your eye onto them blocks the view.

Even if you can’t see a line with infinitely many reflections, you can see a very large number of them. The number of reflections you see between your eye and whatever opaque thing eventually blocks the view cannot be bounded by any function of the number of mirrors. If you take a diagonal view into a long hallway with its two sides mirrored, the number of reflections will be proportional to the length of the hall, even though there are only two mirrors. And with larger numbers of mirrors, more complex patterns of reflection can occur.

Because the number of reflections can be large, finding the eventual fate of a reflected light path by directly simulating the sequence of reflections any ray might take could be very slow. Instead, my new paper shows that it can be done in polynomial time! More precisely the time is polynomial in the number of mirrors and in the number of bits needed to specify a mirror coordinates or viewpoint direction using binary numbers.

Although the problem is simple to state, the solution uses sophisticated methods from computational topology. It’s an application of an idea from an earlier post, originally by Mark Bell, and included in an update to my earlier preprint “The Complexity of Iterated Reversible Computation”. This idea concerns iterated integer interval exchange transformations: if you have a function on an interval of integers that acts by permuting subintervals, then how easy is it to compute the result of applying the same function many times? As Bell observed, this computation could be transformed into an equivalent problems of tracing normal curves on a topological surface, which had been solved in earlier work by Erickson and Nayyeri. The new paper generalizes these integer transformations to partial functions, extends the same method to compute iterated values of these partial functions, and shows that these partial functions can be used to model the way the mirrors in a mirror maze permute sightlines.