Long contours and chessboard coloring

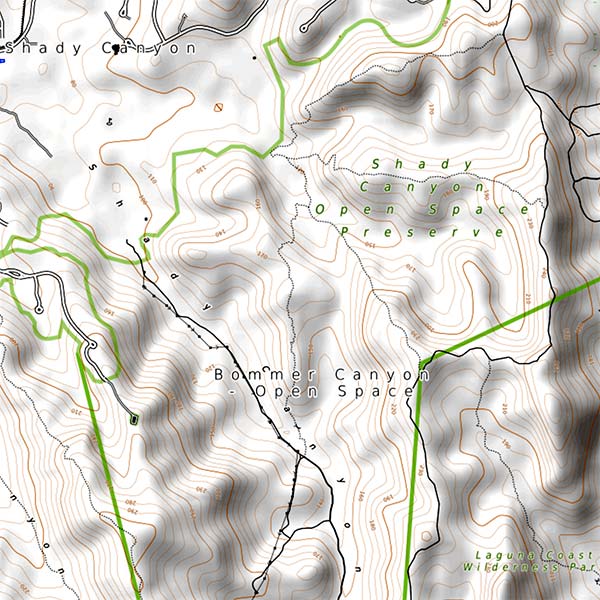

The image below is a topographic map of some parkland a couple miles from my house, clipped from opentopomap.org.

Here’s another picture of the same place that I took a few years ago.

It’s pretty hilly there, as you can tell from the brown contour lines on the map, sets of points that are all at the same height as each other. Some contours are short closed curves. Typically these surround hilltops, although they could also mark basins in the landscape; it’s dry enough here that a basin wouldn’t necessarily stay filled with rainwater. Others wiggle around for quite a long distance before escaping the map and connecting to its surrounding regions. Some of them (including the darker brown curve surrounding a pair of hilltops in the upper left of the map) look like they cross or touch themselves at a saddle point of the landscape. This kind of point, where four or more branches of a contour meet, can indeed happen for a contour at the exact height of a saddle point, but a closeup inspection of the upper left one reveals that it has slightly lower height and is actually a single simple closed curve around both hills. It is also possible for contours to reach a dead end (for instance when they follow the top of a level ridgeline) or for an odd number of branches to meet at a junction.

It turns out that every possible landscape has a contour that stretches from one edge of the map to the opposite edge. To state this more precisely and avoid fractal difficulties, let’s model the landscape as a polyhedral terrain or triangulated irregular network, the graph of a piecewise-linear continuous function from a planar polygon \(p\) to the height at each point. Its level sets are inverse images of heights, and its contours are connected components of level sets. They might not actually be curves or lines; for instance a level plain in the landscape would belong to a single contour. Every contour touches the boundary of \(P\) in a (possibly empty) set of points, dividing the boundary into arcs. Then the existence of a long contour can be stated more explicitly: there is a contour such that all of these arcs have length at most half the perimeter of \(P\). If \(P\) is a rectangle or square, this long contour touches two opposite sides, possibly at their endpoints, because avoiding both a horizontal side and a vertical side would cause the arc containing those sides to be too long.

The proof sketch is not particularly difficult but I’ve indented it below so you can skip over it anyway:

Start with the contour containing an arbitrary boundary point, and suppose that it doesn’t immediately solve the problem. This means that there is an arc (and there can be only one) between two of its boundary points (say clockwise from \(x\) to \(y\)) that covers more than half of the perimeter of \(P\). Now consider what happens if you move clockwise continuously from \(x\) to some point \(x'\), and then walk along a contour from \(x'\) (staying to the left whenever you have a choice) to reach another boundary point \(y'\). Then \(y'\), wherever it is, must be within the arc from \(x\) to \(y\), because the two contours cannot cross, so the arc from \(x'\) to \(y'\) is shorter than the arc from \(x\) to \(y\). As we move \(x'\) continuously away from \(x\), the position of \(y'\) moves continuously in the other direction away from \(y\), except at points when the contour passes through a vertex of the landscape; at those points the contour can change its shape discontinuously and \(y'\) can jump discontinuously. But regardless of whether \(y'\) changes continuously or jumps, the length of the arc from \(x'\) to \(y'\) decreases as \(x'\) and \(y'\) move towards each other until eventually they cross.

At some point before they do cross, one of two other things must happen. Either the length of arc \(x'y'\) decreases continuously through half the perimeter, or it jumps from being larger than half the perimeter to being smaller than half the perimeter. If it decreases continuously through half the perimeter, the contour containing the points \(x'\) and \(y'\) at the time that it reaches exactly half the perimeter has the desired property. If it jumps, consider the contour \(C\) exactly at the point when it jumps. If \(C\) has the desired property, we are done. Alternatively, there might still be a long boundary arc \(uv\) for \(C\), nested within the pre-jump arc \(x'y'\), and we can continue the same process from there until eventually terminating in one of the other cases.

(Exercise: Use this method to find a long contour in the topographic map.)

That was all very continuous and topological but I actually came to this problem from something much more discrete: If you color the squares of a chessboard with three colors, must there be some two of the three colors whose squares stretch all the way across the board, touching edge to edge? In contrast, with four colors you can make colorings where all two-color regions are small:

The four-coloring above is proper (no two adjacent squares have the same color) and I can use contours prove that every proper three-coloring has a two-colored region that stretches across the board.

The idea is, first, to turn any three-coloring of the chessboard squares into a discrete height function, one that takes integer values on each square and where these values differ by \(\pm 1\) on adjacent squares, so that the coloring can be recovered by taking the heights modulo three. I discussed this briefly in an earlier post about reconfiguring Miura-folded origami, with the following example:

It doesn’t look very continuous, but we can make it continuous by using these height values only for the middle points of the squares. At each corner point where two or four squares come together, set the height value to be the average of the heights of the squares that meet there. Divide each square into four isosceles right triangles, meeting at the center of the square, and interpolate these height values linearly within each triangle. Then, find a long contour for the resulting polyhedral terrain. If the long contour is at an integer height, it can be turned into an edge-to-edge sequence of squares using that height and either one of the two neighboring integer heights. If the long contour is at a non-integer height, it can be turned into an edge-to-edge sequence of squares using the integer heights closest to it above and below that height. The image below shows the integer and half-integer contours of the same grid 3-coloring, with the long contour through the large red-yellow region shown in bold. The crosshatched regions are level shelves in the surface, and the black dots are peaks and basins.

Sadly, the same argument doesn’t work for improper three-colorings, because they don’t usually have height functions. More strongly, the property that we want to prove, the existence of large two-colored regions, is just not true of improper colorings. The improper coloring below can be extended to arbitrarily large chessboards, with all two-colored regions having at most 13 squares: