Bricard's jumping octahedron

The Schönhardt polyhedron is a non-convex octahedron that can be formed from a convex regular octahedron by twisting two opposite faces, stretching and deforming the other faces as you twist. It’s well known for not having any interior diagonals, and for being impossible to subdivide into tetrahedra without introducing new vertices. But long before Erich Schönhardt described it in 1928 in connection with these properties, Raoul Bricard was investigating flexible octahedra, in connection with Cauchy’s theorem on the rigidity of polyhedra. The Schönhardt polyhedron forms an interesting example of flexibility, as I learned from a 1975 collection of lecture notes by Branko Grünbaum on “Lost Mathematics”). I’m not entirely sure that it was known to Bricard (it’s not clear from Bricard’s paper and Grünbaum doesn’t really say so) but it wouldn’t surprise me if it was.

Cauchy’s theorem states that the shape of every convex polyhedron is uniquely determined by the shapes and connectivity of its faces. There can be no other convex polyhedron that has faces of the same shape, connected in the same way. But in some cases (like the regular icosahedron) you can dent some of the faces in to make a different, non-convex polyhedron with the same face shapes and connectivity. So Cauchy’s theorem doesn’t immediately extend to non-convex polyhedra. In fact, certain non-convex “flexible polyhedra” can deform continuously into an infinite range of shapes, without changing the shape or connectivity of their faces. Bricard’s octahedra are self-crossing examples and later investigators found examples without self-crossings.

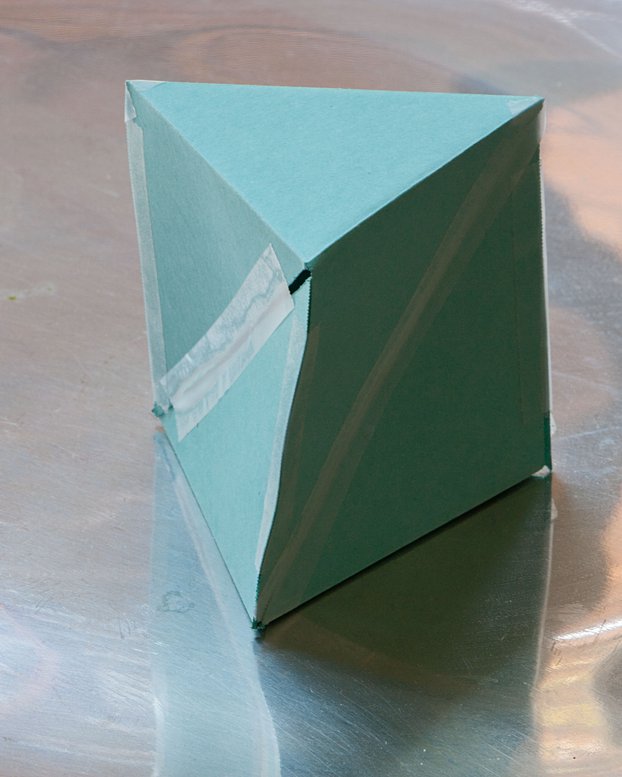

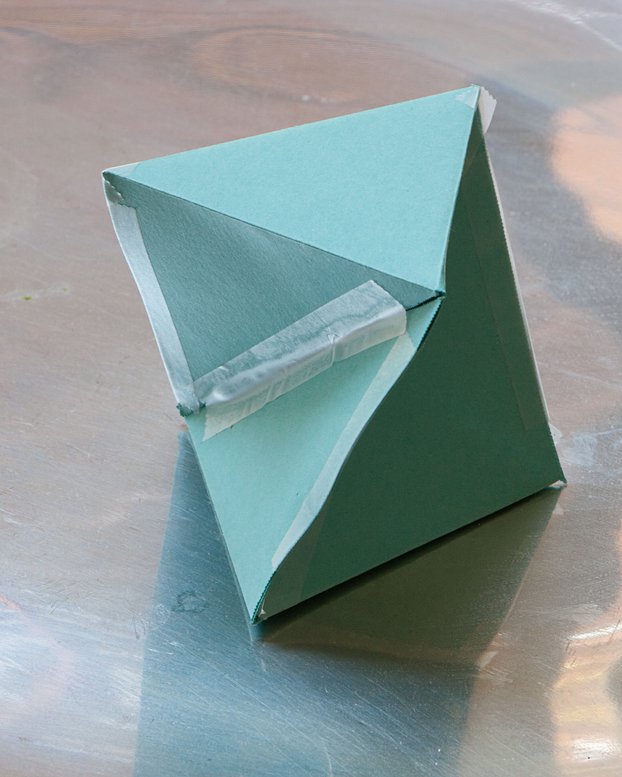

But Grünbaum describes a different, non-self-crossing non-convex octahedron, the “jumping octahedron”. Rather than having a continuous range of rigid shapes, it has exactly two shapes, both of which have faces of the same shapes and connectivity. Unlike the example of the regular icosahedron and dented icosahedron, the two shapes have dihedral angles that are convex and concave in the same places. If you make this polyhedron out of perfectly rigid faces, with hinged connections at their edges, it could only be in one or the other of its two shapes: you wouldn’t be able to get it to the other shape without taking it apart and rebuilding it. But if you make it out of a material that’s stiff enough to hold its shape but flexible enough to deform a little, you can make a model that jumps or snaps from one shape to the other when you twist it. If you deform it a little out of shape, it will snap back to the nearest of its two valid shapes. Here’s one I made very roughly from some light cardstock and transparent tape, in its two shapes, one with only slightly-concave long diagonals down its sides and the other much more twisted and folded up:

|

|

My model makes an interesting squelchy sound when I twist it from the more upright shape to the more twisted one, because these two shapes have different volumes and the air has to get out through the cracks between the faces. If I had perfectly sealed all these cracks, the pressure change would prevent it from changing shape. This change in volume is a big contrast from the Bricard octahedra and other continuously-flexible polyhedra, which must maintain constant volume as they flex.

The net I folded it from looks like this:

It’s in two parts in order to make the seams of my model be symmetric, but also that way it fits better onto a single sheet of paper or card. It consists of two equilateral-triangle faces (the faces at the top and bottom of the model shown above) and six identical obtuse triangles on the sides. In my net and model, these triangles are isosceles, but that’s not important. The important part is that, if one of these triangles is projected onto the line between it and the equilateral triangle, its projected length is slightly more than the length of the connecting edge (because it’s an obtuse triangle) but not too long: longer by a factor strictly between one and

\[\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\approx 1.07735.\]If you make the projection too short (with a right or acute side triangle shape) then it will not have two different shapes that maintain the same faces and convex-concave relation at each dihedral. If you make the projection too long, then you won’t be able to put it together at all while keeping all the faces flat. An explanation for some of this behavior can be seen from the diagram below, which shows the bottom equilateral triangle and one of the obtuse side triangles of the polyhedron, flattened out into a single plane, from a top view.

If you fold these two triangles on their connecting edge, keeping the bottom equilateral triangle fixed but lifting the obtuse triangle into space, then the outer vertex of the obtuse triangle will rotate through a semicircle, but the plane of this semicircle is perpendicular to the plane of view of the diagram, so in top view it just looks like a line, the red line in the diagram. The edge along which the two triangles are attached is the axis of rotation, so it’s perpendicular to the semicircle of rotation and to the projected red line. If you fold all three edges of the bottom equilateral triangle at equal angles, then by symmetry the tips of the three folded obtuse triangles will form another equilateral triangle, and the size of this equilateral triangle will depend on the fold angle. If the vertices of this second equilateral triangle project to points on the yellow circle (the circumcircle of the bottom equilateral triangle) then this triangle will have exactly the correct size to attach the top face. This is only possible when the vertex of the obtuse triangle in the drawing is folded to a point that projects to of the two crossings of the red line and the yellow circle. The two fold angles for which this happens give the two shapes of the jumping octahedron.

The constraint that the side triangles be obtuse is what is needed to make the two crossing points of the red line and the circle be in the same arc of the circle relative to the vertices of the bottom equilateral triangle. The constraint that their projected length should be only a little bit longer than the side length of the equilateral triangle is what is needed to make the red line cross the circle at all. So these two constraints are necessary to make the jumping octahedron work. There’s one more necessary constraint: the height of the obtuse triangle above the edge connecting it to the equilateral triangle has to be large enough to reach both of the crossing points of the red line. When I started to make the model I was worried about a different geometric constraint: maybe the twisted state of the model is so twisted that its inner folded parts cross each other near the center of the model? But that can’t happen. If it did happen, the projected view of the model would have the side triangles folded into a position where they cover the center of the yellow circle. But that would mean that the top triangle’s vertices are too far around the yellow circle, past the point where the farthest point of the red line can cross.