Asymptotics of Recamán's sequence

Recamán’s sequence is a sequence of natural numbers in which the zeroth number is zero and the \(n\)th number adds or subtracts \(n\) from the previous number, subtracting if that would lead to a new value and adding otherwise. It was popularized in a 2018 Numberphile video that showed both an interesting visualization of it using nested circles and a spooky piano composition obtained by using its values as notes.

In the OEIS entry for this sequence Benjamin Chaffin claims to have computed and plotted its first \(10^{230}\) numbers. Can it really be done this fast? And until recently, the sequence’s Wikipedia article claimed that when computing this sequence, each number takes \(O(n^2)\) time to compute, sourced to the analysis in a blog post with a MATLAB implementation. Can it really be this slow?

In analyzing the complexity of computing integer sequences, it’s often important to consider numerical precision. The standard computational model used for algorithm analysis, the unit-cost RAM, allows constant-time arithmetic on \(O(\log n)\)-bit integers, enough to allow the model to index its memory. Models of computing with larger word sizes are less standard. And some sequences need linearly many bits just to represent a single sequence value, too many to handle in constant time. But that’s not an issue for Recamán’s sequence. Even a sequence that always added \(n\) at each step, rather than sometimes, subtracting, would grow at most quadratically, allowing the first \(n\) numbers to be computed using only \(O(\log n)\)-bit arithmetic.

Using this model, we can analyze a naive algorithm for the sequence that directly implements its recurrence while maintaining a set data structure to keep track of what has been seen already.

def recaman():

visited = set()

a = n = 0

while True:

yield a

n += 1

if a > n and a - n not in visited:

a -= n

else:

a += n

visited.add(a)If sets are represented using hash tables with provable constant expected time per operation (say, linear probing with tabulation hashing), then this takes constant expected time per number, or \(O(n)\) for the first \(n\) numbers. So much for being quadratic. Alternatively, if we knew that the sequence grew only linearly, we could avoid hashing and expected time analysis by using a bitvector to get deterministic constant time per number.

So the next question to ask is: does the sequence grow only linearly, or more quickly? Before running an experiment to test this, my intuition was that if the choice to add or subtract were uniformly random, then the sequence would grow like a random walk, typically \(\Theta(\sqrt n)\) steps away from the origin, which with step size \(\Theta(n)\) would give growth \(\Theta(n^{3/2})\). On the other hand, to achieve equal probability of going up or down you need roughly half of the integers to be visited, and for that to happen the sequence should grow only as \(\Theta(n)\). For any faster growth rate, the density of visited integers would be less than half and the sequence would be pulled downward. So I expected that the true growth rate should be at a level where the upward pressure of a uniform random walk and the downward pressure of less-than-half occupancy balance each other, but I didn’t have a strong a priori feeling whether this meant linear growth (with constant but somewhat less than half occupancy) or slightly superlinear growth.

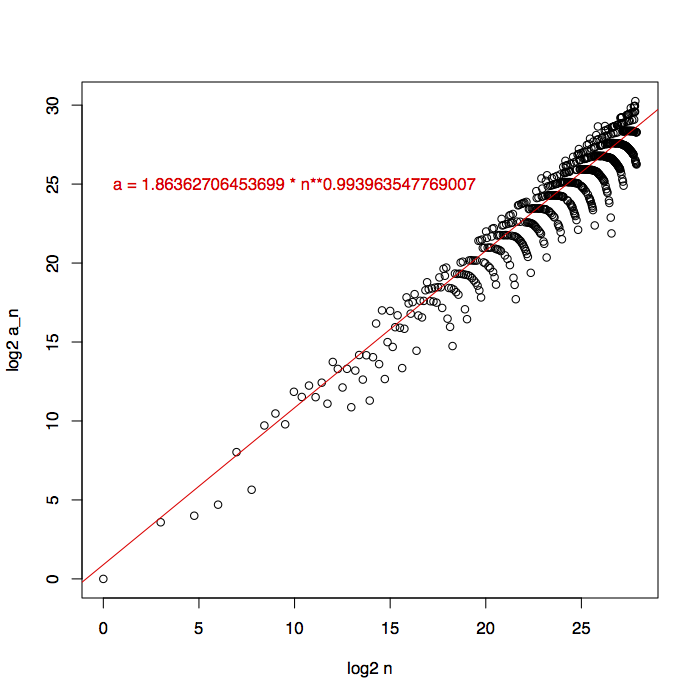

This is something we can check experimentally, so I used the naive algorithm to generate a quarter-billion sequence elements, sampled them down to 629 pairs of \((n,a_n)\) by keeping only elements at cubic positions, and fit a line to their log-log plot using Siegel’s repeated median estimator in R. The result has weird stripy patterns that don’t look much like a line, but its exponent looks a lot like a 1 to me.

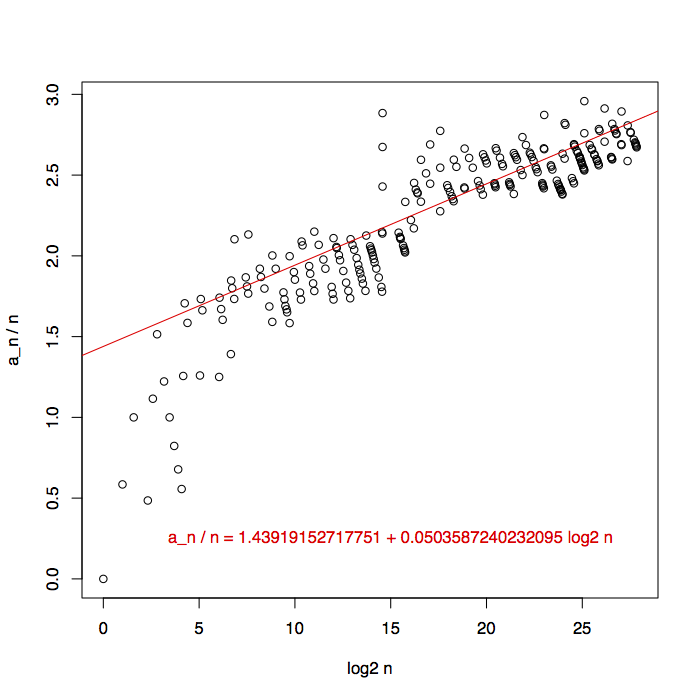

We can get a cleaner curve (and a more informative picture of how big a bitvector we might need) by plotting only the points where the sequence reaches a new high point. There were too many data points to fit easily, so I thinned them out by including only high points that were half a percent higher than the previous one, giving me 254 data points. To look more carefully at near-linear growth rates, I plotted \(a_n/n\) against \(\log n\) this time. Again, the results had weird stripy patterns that I didn’t expect (I thought filtering for the high points would have eliminated that), but the plot seems to clearly show that the growth rate of the sequence is nonlinear. Although the fit line shows growth of the form \(\Theta(n\log n)\), I don’t think the data is clear enough to conclude that this is the right growth rate.

So, sadly, the bitvector solution doesn’t appear to give us a deterministic solution with constant time per element. It takes a nonlinear amount of time to initialize a nonlinear number of bits. Maybe instead some deterministic choice of hash function allows the hashing solution to work without randomization, but proving that seems difficult. On the other hand there’s a lot of other structure in the sequence. Maybe we can take advantage of it and get even faster, computing an implicit representation of the sequence (rather than an explicit list of each of its elements) in time sublinear in the number of elements generated? Surely, if the claim of having generated \(10^{230}\) elements is to be believed, this must be possible.

A hint comes from the plots in the MATLAB post showing that Recamán’s sequence contains long alternations between addition and subtraction that fill in two contiguous blocks of integers. A comment by Jan Van lent from a 2016 blog post on The Math Less Traveled suggests that there should be few (maybe \(\Theta(\sqrt{n})\)) of these blocks, and that we can save space using a data structure that stores blocks rather than individual numbers. This would have advantages even in the naive algorithm: when I tried bumping my data sets to a full billion elements they bogged down, not because I didn’t have enough time to run four times slower, but because I ran out of memory for the hash table.

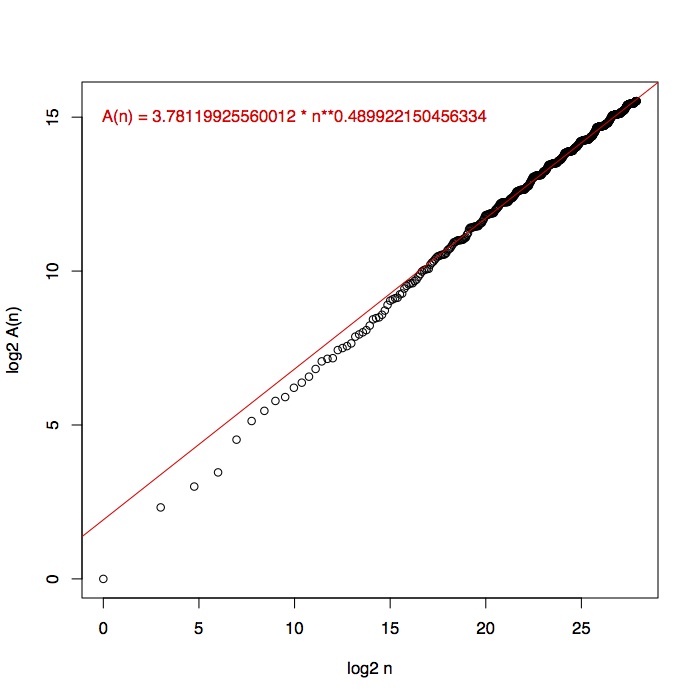

We can use a data structure that allows for integer predecessor queries to store only the starting endpoints of each block of occupied integers, associating with each start the end of the same block. Then, we could test whether a query integer \(q\) is in one of the blocks by finding the predecessor of \(q\) (the first block start at or before \(q\)) and checking whether its block extends as far as \(q\). A similar but more complicated calculation could also be used, for each sequence element, to find the length of the alternation starting at that element (stopping the alternation when the negative steps in the alternation run into another block), and then to update the collection of blocks to cover all of the elements encountered during this alternation. The obvious choice of predecessor data structure would be a balanced binary search tree, but (because we’re dealing with integers of polynomial magnitude) it’s better in theory to use a Van Emde Boas tree, which can handle each data structure operation in time \(O(\log\log n)\). If we generate Recamán’s sequence one alternation at a time in this way, and it has \(A(n)\) alternations and \(B(n)\) blocks in its first \(n\) elements, then the improved generation algorithm will take time \(O(A(n)\log\log n)\) and space \(O(B(n))\). I have a VEB-tree implementation, but it lacks predecessor queries, and four times more elements are only a small step on my log plots, so I haven’t tested this. But we can still use the naive algorithm to compute \(A(n)\) and \(B(n)\) and study how they grow. Here, first, is \(A(n)\).

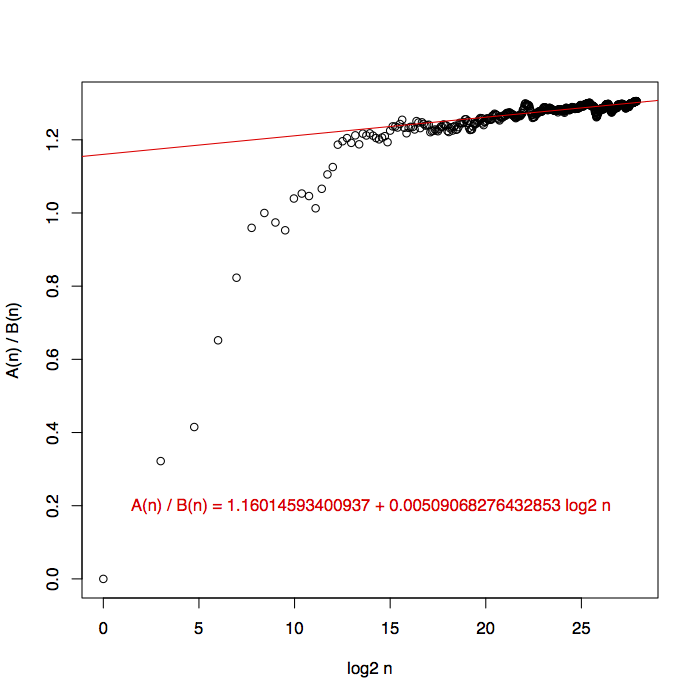

The number of alternations looks like a reasonable fit for \(\sqrt{n}\). The number of blocks can be at most twice the number of alternations, but it could well be smaller as blocks coalesce after they are formed. The plot of numbers of blocks looks almost the same as the one above, so instead I plotted a ratio. I don’t think the fit line in the plot is particularly convincing. Nevertheless to me this looks like \(A(n)\) and \(B(n)\) have the same exponent but differ by a lower-order factor like a log or log-log.

So what have we learned?

-

Even the obvious hashtable-based methods can achieve constant expected time per element. But their limiting factor is memory, not time.

-

It’s tempting to use bitvectors instead, and that might not be a bad choice in practice, but in theory that appears to take more than constant time per element. Deterministic hashing might take constant time per element but this is unproven.

-

Generating the sequence implicitly in terms of its alternations, and using a data structure that represents the generated elements in terms of their blocks, looks like it can achieve something like \(O(\sqrt n)\) in both time and space, but again this is unproven.

-

This is still not anywhere near fast enough to get \(10^{230}\) elements, nor even \(10^{230}\) as the largest generated value. So either something is wrong with that claim (most likely a typo in the number of elements), or there are significant algorithmic improvements possible beyond just using alternations and blocks.

For the source code for these plots, see density generation/analysis, high point generation/analysis, alternation generation/analysis, and block generation/analysis.