A little knowledge can make the next step harder

Suppose you have a fill-in-the-unknowns puzzle, like Sudoku. Can making some deductions and filling in those parts of the puzzle make the whole thing harder to solve than it was before you started? Sometimes, yes!

I have in mind human-style puzzle-deduction rules, where you see a piece of the puzzle that matches some pattern and use that to deduce what one of the unknowns should be. And by “harder” I mean that a puzzle that was previously possible to solve by some set of deduction rules, after the deduction, stopped being possible for those rules to solve. Of course this is possible if you have a bad set of deduction rules. But normally, at least for the kinds of patterns I think about when solving puzzles, if a pattern matches in a partially completed puzzle, then it or a simplification of it will continue to match no matter how I fill in more of the unknowns. Most of the deduction pattern that I use are monotonic, in this sense. If you had a collection of patterns that was not monotonic, you could add all ways of partially filling them in to your collection, and get a better set of patterns, right?

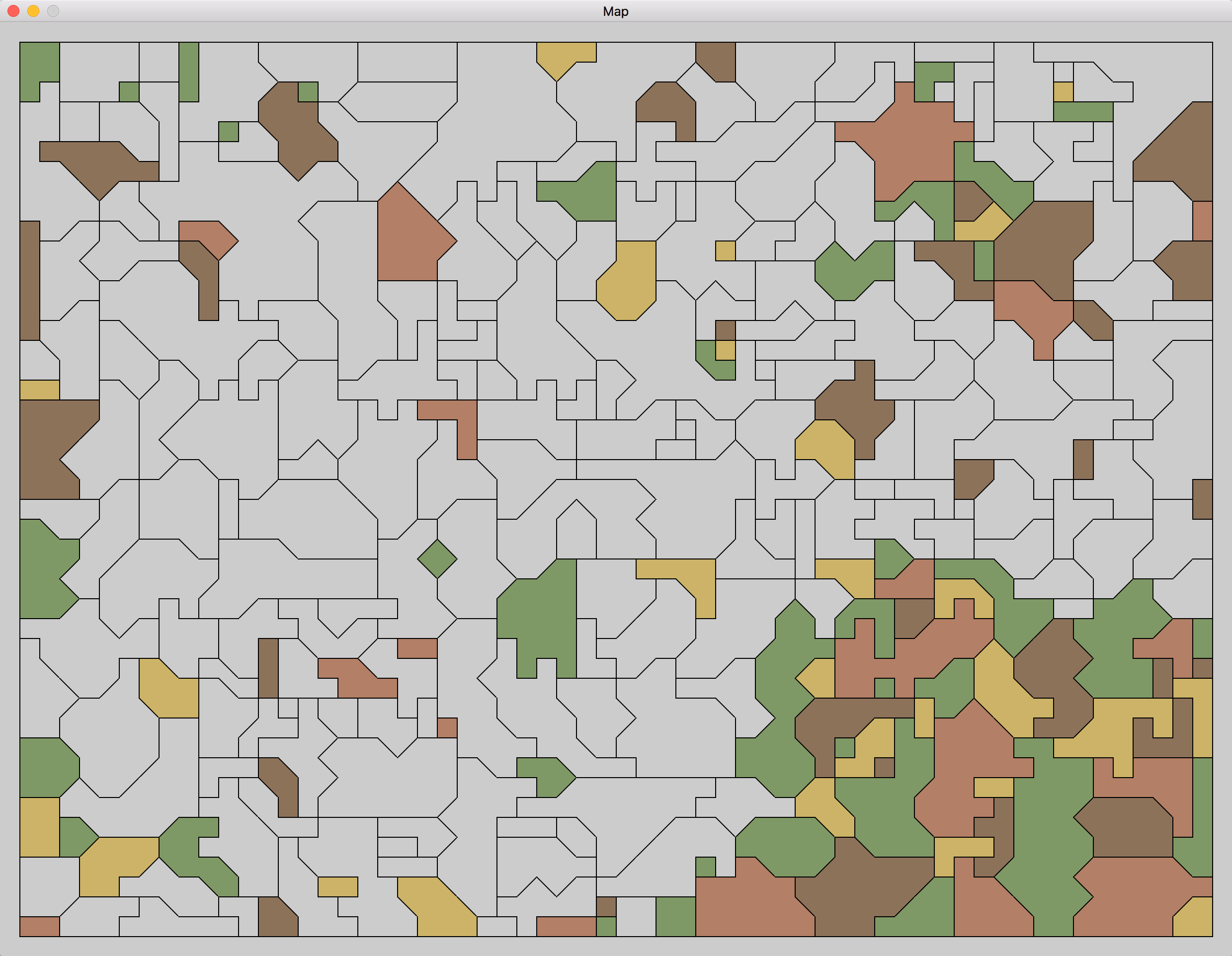

Wrong! There can be valid deduction patterns for which this extension to monotonic sets would produce invalid patterns. I’m pretty sure this can happen in Sudoku, actually, but the example I have in mind comes from a different puzzle game I’ve been playing lately, part of Simon Tatham’s puzzle collection, where it’s called “map”. It’s based on the problem of precoloring extension: you’re given a partially 4-colored planar map, and you have to fill in the rest of the colors. And it’s trivially NP-complete, by a reduction from planar 3-coloring (augment a 3-coloring instance by extra vertices of the fourth color, preventing any of the given instance vertices from having that color) but the puzzles usually presented by the puzzle app are solvable by hand, even when they’re large and at the highest of its levels of difficulty.

If that were all, then I think all deduction rules could be made monotonic. But I’m going to tell you one more thing about the puzzle, and this one thing makes it non-monotonic. It is that, like Sudoku, every puzzle has a unique solution. And like Sudoku, the assumption of uniqueness leads to new deduction rules. You can infer that certain regions have to have certain colors, because if they could be colored anything else then there would be more than one solution.

To see how this works, suppose I had a map like the one shown below (where the white squares have not yet been colored, and I’m only showing a small piece of a larger puzzle):

There’s a pocket of uncolored squares extending into the colored region on the left. If I colored the square at the mouth of the pocket yellow, the inner square of the puzzle would be ambiguous: it has only yellow and blue neighbors, so it could be either red or black.

To prevent this ambiguity, the square at the mouth of the pocket must be black. And to force it to be black, the square one step beyond the mouth must be yellow. So from the initial state and the assumption of a unique solution, it’s possible to infer the colors of three previously-blank squares:

But if I have multiple rules at hand, it’s natural for me to try the weaker and easier ones first. Suppose I had done this, and used a weaker inference rule telling me that the square at the mouth was black.

Or suppose I had used a rule that produced the valid (but even weaker) inference that the inner square must be red.

Now I can’t use my strong inference rule and color the outer squares! I’ve lost the information about why I colored the inner pocket squares the way I did, and so I’ve lost the ability to make deductions about how the outer squares should be colored to avoid ambiguities. It would not be a valid pattern to see a puzzle in these states and deduce the color of the remaining squares associated with the pocket. So the extension from my initial (valid) rule, which filled in all three squares when they were all blank, to a monotonic rule that fills in the partially-filled-in pocket in the same way, would be invalid. Of course, if the puzzle solution was unique before, it must still be unique after partially filling in the pocket. But with fewer squares colored, my deductive abilities might not be up to the task of reasoning from the remaining parts of the puzzle to its unique solution.

For the same reason, I might not actually want to color yellow the square beyond the mouth, forgetting why it needs to be yellow. Because what I can infer from the initial state is not merely that it should be colored yellow: it’s that the three outer neighbors of this square must have a permutation of the three other colors, so that this square is forced to be yellow, so that the rest of the pocket will have an unambiguous coloring.

I think what this means is that my knowledge representation (consisting only of blank or filled-in puzzle regions) is inadequate. In practice, I actually use a more complex knowledge representation where (either in my head or with markers provided in the puzzle app) I keep track of which colors are still available for the blank regions, but it’s still inadequate, in the same way. It’s not clear to me what the right knowledge representation is, to allow me to keep track of chains of inferences like “one of these squares must be red to prevent this square from becoming yellow to prevent its neighbor from becoming ambiguous” without the complexity of what I remember for each square blowing up to non-constant.