Fingerprints and tangent bundles

The arXiv version of “Geometric fingerprint recognition via oriented point-set pattern matching”, my CCCG paper with Mike Goodrich, Jordan Jorgensen, and Manny Torres, has now appeared: it’s arXiv:1808.00561

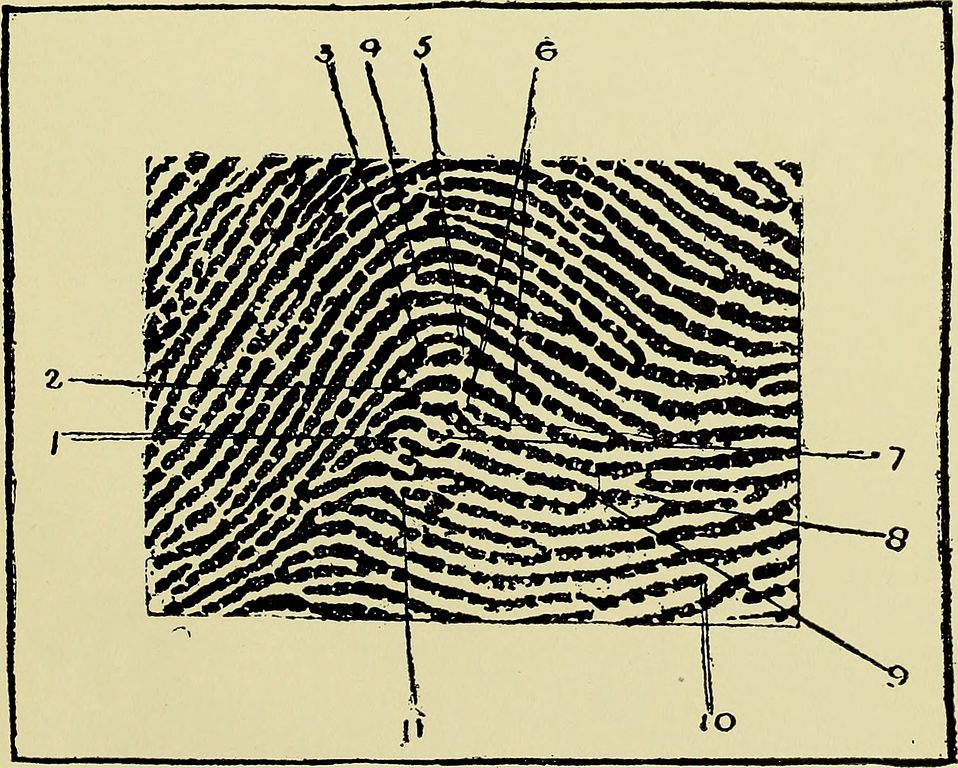

The motivating problem for this work is to approximately match human fingerprints. The image below is a vintage example, from Guide to Finger-print Identification (Faulds, 1905):

Fingerprints can be described combinatorially by their minutiae, points where the fingerprint pattern changes. These are points like the marked ones in the image. For instance they include the points at the ends of ridges or at the merger of two ridges. Once the fingerprints are described as sets of minutiae, the problem becomes one of matching one point set to another. But this is complicated by the fact that (beyond being labeled by the type of change they describe) the minutiae are not just pure Euclidean points. Each one is associated with a direction, as well as a position: the direction in which the associated ridges extend from the point. So the space in which the minutiae live is \(\mathbb{R}^2\times S^1\), the product of a Euclidean plane with a circle of directions. Or, if you like, it’s the unit tangent bundle \(\operatorname{UT}(\mathbb{R}^2)\).

Transformations of the Euclidean plane such as translations, rotations, and scaling extend in a natural way to this space. The goal in our paper is to find a transformation by which a given small pattern point set (the minutiae that we find for a particular fingerprint scan) can be made to look like a subset of a larger host point set (all the minutiae). Here “look like” involves a definition of similarity of two point sets that combines both Euclidean distance and the differences between the orientations of points. The approach we take to finding the right transformation is more or less standard in this area: start by choosing a family of transformations that match certain representative points exactly, prove that one such transformation is within a constant factor of optimal, and then search within a larger family of perturbations of these exactly-matching ones, in order to reduce the constant factor to \(1+\varepsilon\).

This does have some weaknesses, though. One is that the host point set has to include an approximate transformed copy of every pattern point, but real fingerprint databases are likely to be missing some minutiae. Another is that by measuring the quality of a match by the pair of points that are least well matched to each other, we are very vulnerable to outliers in the data (points that are perturbed, or completely missing). It would be better to use a more robust measure of the distance between two point sets. So I think there’s still plenty more research to do in this direction.