Drawing clustered graphs (slowly)

Clustered planarity is a simple enough problem to state: we have a hierarchically clustered collection of vertices (say employees of a company grouped into the company’s subdivisions, or subroutines in a software project, grouped into modules) together with a graph on the same vertices (who actually talks to whom at their lunch breaks, or which subroutines call each other) and we want to visualize both together.

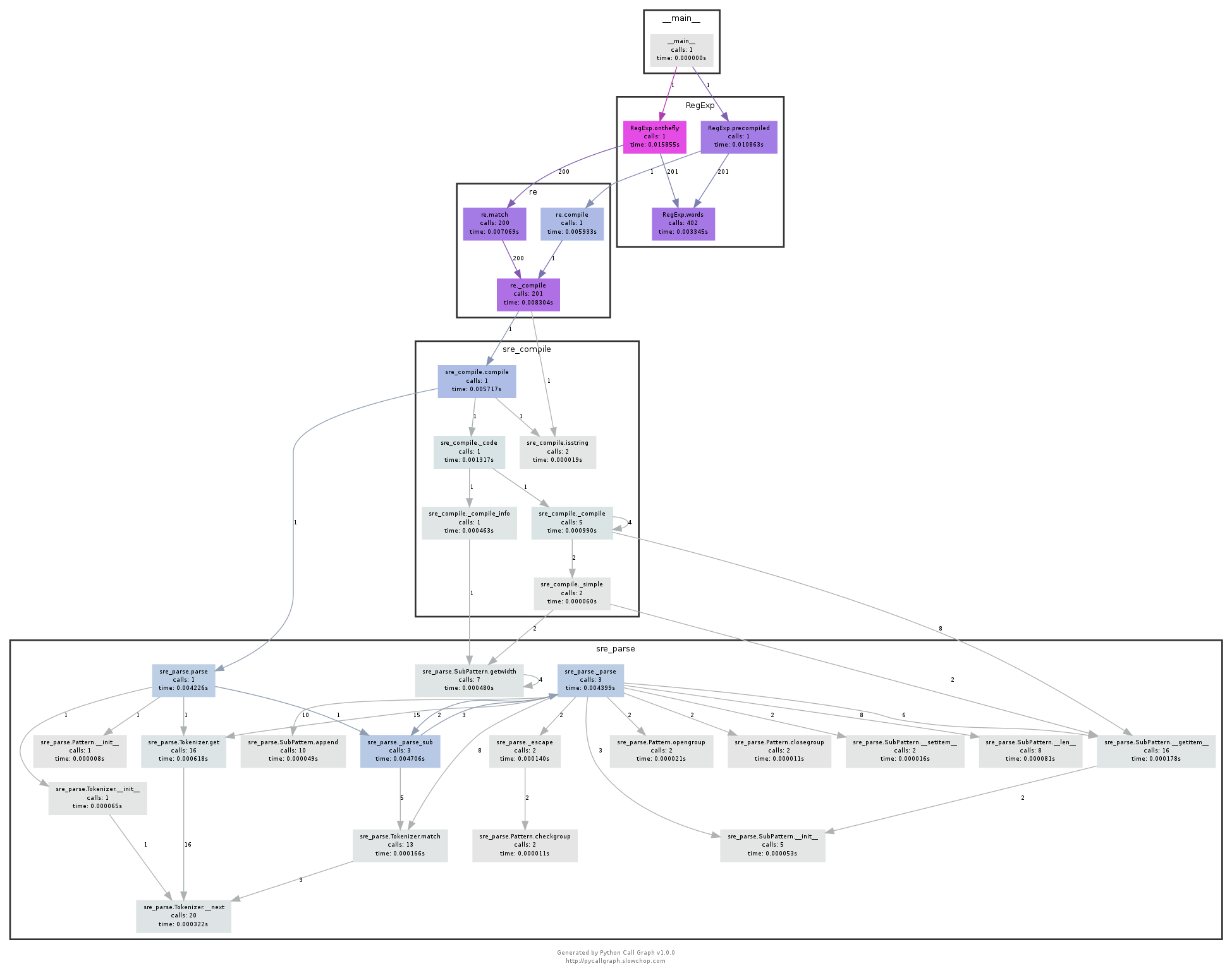

Call graph of Python regular expression code, from the pycallgraph documentation

An ideal drawing (if possible) would avoid crossings of pairs edges and of pairs cluster boundaries, and unnecessary crossings of an edge with a cluster boundary. It is not possible to create a nontrivial drawing of this type without some edge-boundary crossings, for edges that have one endpoint on each side of the boundary. But we don’t want any other crossings beyond those necessary ones. When this can be done, the drawing is called “clustered planar”.

Despite the simplicity of the problem statement, research on clustered planarity has been something of a mess. We don’t know whether finding a clustered planar drawing of a given graph and clustering can be done in polynomial time. We don’t know whether it’s hard for any natural complexity classes. And so instead many of the papers in this area study special cases that can be solved efficiently. Sometimes the restrictions of these cases are natural (e.g. each cluster induces a connected subgraph), and sometimes they’re not (“either the disconnected clusters all lie along a single root-to-leaf path of the cluster hierarchy, or each disconnected cluster has connected parent and siblings”). I think the assumption behind this line of research is that clustered planarity really should be polynomial, and that we can prove it by starting from these cases and generalizing them a bit.

My new preprint, “Subexponential-time and FPT algorithms for embedded flat clustered planarity” (with Giordano Da Lozzo, Mike Goodrich, and Sid Gupta, arXiv:1803.05465) takes a somewhat different approach. It asks: what if clustered planarity is not really polynomial? We’d still want to solve it anyway. How quickly can we do it?

Unfortunately we couldn’t get away from special cases entirely. That’s what the “embedded flat” parts of the title mean: we only handle inputs where the planar embedding has already been chosen, so the remaining problem is to draw the cluster boundaries, and we only handle clusters that partition the vertices (like the first image above) rather than being nested inside each other (like the second image). We have two results for these kinds of inputs:

-

A separator-based divide-and-conquer algorithm can find a clustered drawing, if one exists, in time \(2^{O(\sqrt{\ell n}\cdot\log n)}\). Here \(\ell\) is the maximum number of edges in a face of the drawing, and \(n\) is the number of vertices. The reason for the dependence on \(\ell\) is that we need the separators we find to be simple cycles, so we can’t use forms of the planar separator theorem that find more general separators of size \(O(\sqrt n)\) regardless of face size.

-

Clustered planarity for these inputs is fixed-parameter tractable when parameterized by the embedded-width and number of disconnected clusters of the input. Here embedded width is a variant of treewidth for embedded planar graphs, introduced recently by Borradaile, Erickson, Le, and Weber (arXiv:1703.07532). The idea is to search for a planar supergraph with connected clusters using Courcelle’s theorem. Bounded embedded-width implies that the graph of all candidate edges (diagonals of the faces of the given embedding) itself has bounded treewidth, allowing this technique to work.

As for whether I believe that clustered planarity should be polynomial or not, in the general case: I have no idea. I’d like it to be polynomial, because having efficient algorithms for useful problems is better than not having them, but I think that it would be easier to prove hard (if indeed it is hard) than to find a polynomial algorithm for the general case (if it is easy). That’s not evidence for either answer, though.