Triangle-free penny graphs are 2-degenerate

A penny graph (the topic of today's new Wikipedia article) is what you get from pennies by shoving them together on a tabletop, keeping them only one layer thick, and looking at which pairs of pennies are touching each other. In a 2009 paper, Konrad Swanepoel suggested that, when there are no three mutually-touching pennies, the number of adjacencies should be at most \( 2n - 2\sqrt{n} \). I don't know how to prove that, and as far as I know the problem remains open. But here's an argument for why the number of edges should be strictly less than \( 2n - 4 \), the upper bound given by Swanepoel.

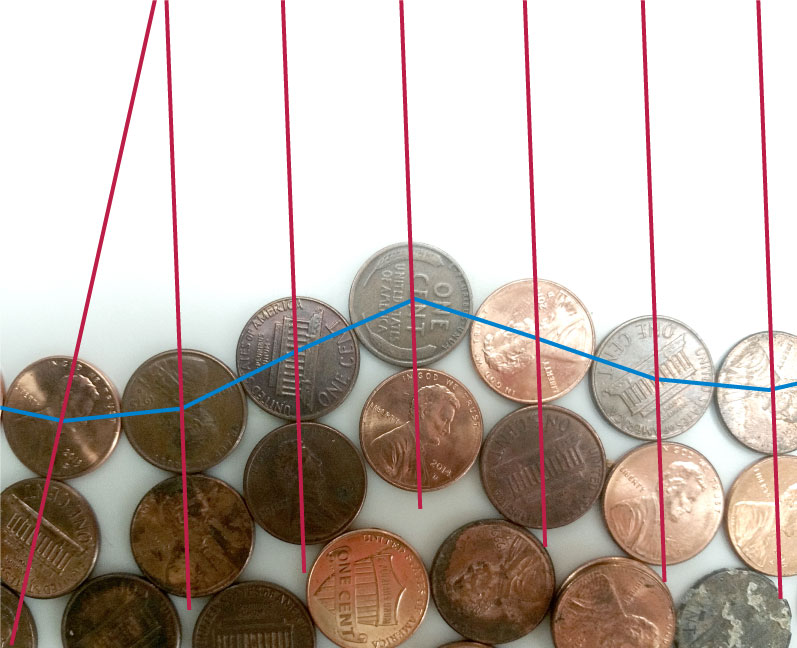

The basic idea is that, in any set of triangle-free pennies, some penny is touched at most twice. Or, in graph theoretic terms, a triangle-free penny graph must be 2-degenerate. For, suppose to the contrary that all pennies had at least three neighbors, and consider the outer face of the planar graph formed by the pennies (marked by the blue polyline below). For each penny on the outer face, draw a line through its center and the center of a neighboring penny that is not one of its two outer-face neighbors (the red lines in the figure).

As you walk around the outer face (clockwise, say) these red lines would always have to point consistently inwards and outwards, so they would have to turn with you, eventually making a complete circuit in the clockwise direction. But they can only turn counterclockwise! If you follow an outer face edge whose adjacent inner face is a quadrilateral, the red lines stay parallel (as they do in most of the picture) and otherwise they turn the wrong way. The impossibility of the red lines making a complete clockwise turn while only turning counterclockwise at each step shows that our assumption, that all pennies have three neighbors, cannot be correct. Therefore, there is a penny on the outer face with at most two neighbors.

Five-vertex triangle-free penny graphs have at most five edges, so by induction \( n \)-vertex triangle-free penny graphs have at most \( 2n - 5 \) edges, very slightly edging out an upper bound of \( 2n - 4 \) given by Swanepoel based on Euler's formula.

The fact that penny graphs are 3-degenerate is a standard exercise, part of an easy proof of the four-color theorem for these graphs. Similarly, the 2-degeneracy of triangle-free penny graphs leads to an easy proof of Grötzsch's theorem for them. So I would be surprised if the 2-degeneracy of the triangle-free penny graphs is new, but I didn't see it when I was researching the Wikipedia article. Does anyone know of a reference?

Comments:

February 20 2017, 19:02:57 UTC

I guess you could get even better (by a constant amount) upper bounds by analyzing bigger finite penny graphs.

February 20 2017, 19:23:58 UTC

Yes, very likely.

February 20 2017, 19:25:41 UTC

This approach can perhaps even be used to prove the \( 2n-\sqrt{n} \) bound. By an argument similar to yours there needs to be not one but at least 2 (or maybe 4 after removing cases which have are 1-degenrate). Next, we argue that there exist a path of length at most \( \sqrt{n} \) in between these two vertices such that removing any prefix makes the next vertex have degree 2. This way when the reach the other original 2-degree vertex has degree 1 giving the \( 2n-\sqrt{n} \) bound. All this might not work but we may get something better.

February 20 2017, 21:29:15 UTC

Actually I think \( 2n – \Omega(\sqrt{n}) \) follows immediately from combining Euler's formula with the fact that the outer face has to have length \( \Omega(\sqrt{n}) \) (in order to enclose \( n \) pennies, by the isoperimetric inequality). But you would need something stronger to get the correct constant factor on the \( \sqrt{n} \) term.

February 21 2017, 04:45:41 UTC

But don't we want a \( 2n – O(\sqrt{n}) \) upper bound?

February 21 2017, 04:52:07 UTC

For an upper bound, but with a negative error term, the correct notation uses \( \Omega \) not \( O \).

February 21 2017, 05:16:35 UTC

Oh of course!