Tiling with antiparallelograms

It's easy to find statements in the literature that the only two kinds of quadrilateral with a single axis of symmetry are the kite and the isosceles trapezoid. But it's not true, unless one forbids self-crossings. There's a third kind of bilaterally symmetric quadrilateral: the antiparallelogram, the shape formed by twisting a parallelogram so that its two longer edges cross each other.

If you apply the usual formula for computing the area of a polygon to an antiparallelogram, you'll get something strange: it's always zero. The formula is computed as a signed quantity, where regions that are surrounded clockwise by the polygon have the opposite sign to regions that are surrounded counterclockwise. The antiparallelogram has two regions that are always congruent to each other but with opposite signs, so they cancel.

With that in mind, I started to wonder: which antiparallelograms tile the plane? Obviously getting a nonzero sum of signed areas from a polygon with zero area is a problem, but we can ignore the signs. And every convex quadrilateral is a tiler, but that doesn't have to be true for a crossed quadrilateral.

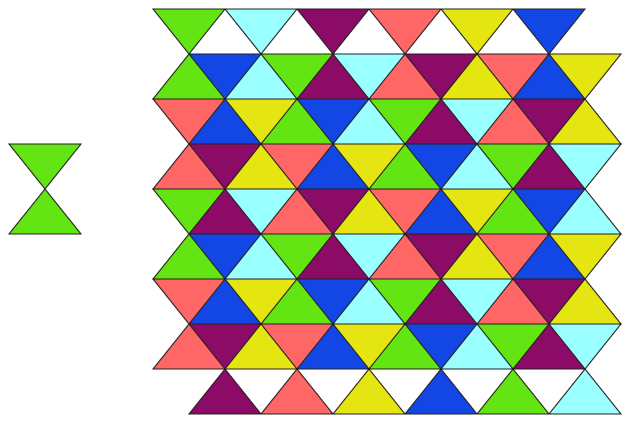

It turns out that every crossed rectangle tiles the plane by translation:

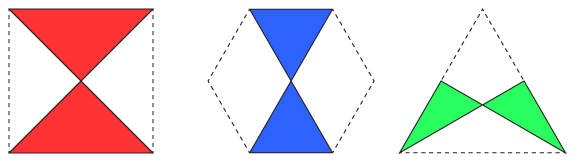

There are also three special antiparallelograms (two of them crossed rectangles) that tile the square, regular hexagon, or equilateral triangle, which in turn tile the plane:

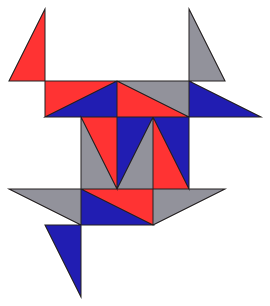

Are these the only antiparallelograms that tile? Some others seem close to working, but just can't quite fit together...

Comments:

2011-08-31T10:39:32Z

Why does the antiparallelogram only have a single line of symmetry?

2011-08-31T15:49:14Z

Well, the crossed rectangle has more than one, just as the rectangles and rhombi (special cases of isosceles trapezoids and kites respectively) have more than one. But in the general case there is only one; for instance, this is true of the one I've shown inside an equilateral triangle, and the one in the last figure.