Skew lines

You've probably seen images of the Hopf fibration, a nice decomposition of 3-dimensional space (or more accurately the 3-sphere) into nested tori, and of the tori into Villarceau circles, so that every point of the space belongs to one of the circles (including the z axis, which can be interpreted as a circle through the single point at infinity) and every two circles are linked.

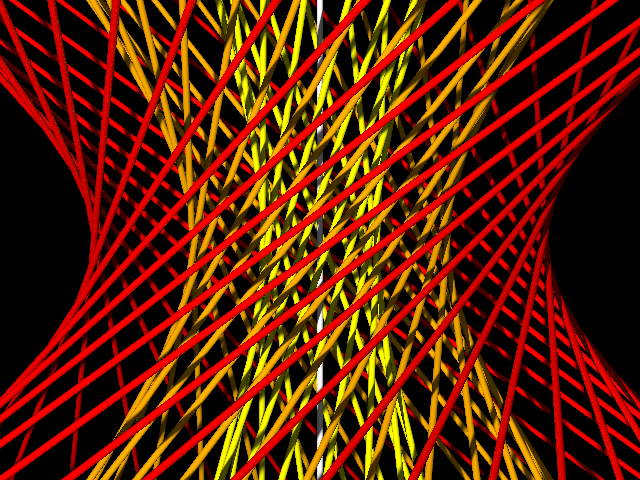

Here's a very similar construction: a decomposition of 3-dimensional space (or more accurately projective 3-space) into nested hyperboloids, and each hyperboloid into lines, so that every point of the space belongs to one of the lines (including the line at horizontal infinity) and every two lines are skew.

It's not hard to construct: each line is the line through the points \( (x-y,y+x,1)\), \( (x,y,0) \), \( (x+y,y-x,-1) \) for some \( x \) and \( y \). The white vertical line in the center of the image is the \( z \) axis (\( x=y=0 \)) and the nested hyperboloids on which the other lines lie are formed from points \( (x,y,0) \) that are all at the same distance as each other from the origin.

I was looking at this in an attempt to improve my intuition about lines in the complex plane. The complex plane as a whole is difficult to visualize because it has four real dimensions, but one can reduce the number of dimensions by one by looking only at the pencil of lines through a single point, and that's what this picture illustrates.

To be more specific, the affine complex plane consists of pairs of numbers \( (p,q) \) where \( p \) and \( q \) are both complex. As a topological space it is the same as the real four-dimensional space defined by quadruples of numbers \( (x,y,z,w) \) where all four numbers are real: just let \( p=x+iy \) and \( q=z+iw \). However it is not the same in terms of which subsets of points are considered collinear or coplanar: real 4-space has lines, planes, and 3-dimensional hyperplanes while the complex plane has only lines. A complex line looks like a plane in real 4-space, but not every real plane forms a complex line.

The lines through the origin in an affine space of some dimension form a projective space one dimensional smaller. For instance, when you use your eyes to look at three-dimensional space, and some two objects lie on a line that passes through the pupil of your eye (which we might as well place at the origin of our coordinate system), then the images of the two objects would project to the same point on your retina; the two objects are equivalent from the point of view of where in your field of view they land, even though they may have very different positions in space. Your retina forms a two-dimensional projective space. Similarly, we might imagine a four-dimensional creature with a three-dimensional retina, and the view this creature would have of four-space is described by three-dimensional projective space. To define this space, consider any two points \( (x,y,z,w) \) and \( (x',y',z',w') \) (other than the origin) as equivalent when one is a scalar multiple of the other: \( (x',y',z',w')=(ax,ay,az,aw) \) for some nonzero real number \( a \). The equivalence classes of this relation are the points of projective three-space. But most of these points have a nonzero \( w \)-coordinate, and whenever that happens we can divide through by \( w \) to get the equivalent normalized coordinate \( (x/w,y/w,z/w,1) \). The first three coordinates of this normalized form are just the familiar three Cartesian coordinates of affine three-dimensional space, so affine space is a subset of projective space. However, projective 3-space also includes some "points at infinity" with a zero \( w \)-coordinate.

Now do the same thing to the complex plane \( (p,q) \): consider two points \( (p,q) \) and \( (p',q') \) to be equivalent when they are scalar multiples of each other. But now the scalar a is allowed to be a complex number rather than a real number. The resulting one-dimensional complex projective line describes the family of lines in the complex plane that pass through the origin. Given a point \( (p,q) \) of the complex plane, it is equivalent to \( (p/q,1) \) whenever \( q \) is nonzero, so we might as well represent its equivalence class by the single complex number \( p/q \), or by a special number \( \infty \) representing the case when \( q=0 \). The resulting projective space, consisting of the complex numbers and the single point \( \infty \) at infinity, is more commonly known as the Riemann sphere.

Every complex line through the origin can be interpreted as a plane through the origin in real 4-space and projected to a line in projective 3-space. And if we work through what this means in terms of the actual coordinates, what we get is either one of the lines through the points \( (x-y,y+x,1) \), \( (x,y,0) \), \( (x+y,y-x,-1) \) of affine 3-space, exactly as in the picture above, or possibly the line at horizontal infinity of the projective space.

This gives us a fibration \( \mathbf{RP}^1 \to \mathbf{RP}^3 \to \mathbf{CP}^1 \) where the fibers (\( \mathbf{RP}^1 \)) are the lines of the drawing, and the map from real projective 3-space (\( \mathbf{RP}^3 \)) to the Riemann sphere (\( \mathbf{CP}^1 \)) is the one formed by mapping the set of real scalar multiples of \( (x,y,z,w) \) to the larger set of complex scalar multiples of \( (x+iy,z+iw) \). I guess this must be same as the Serre fibration \( \mathrm{SO}(2) \to \mathrm{SO}(3) \to S^2 \)? At least, the three spaces in these two fibrations match up correctly with each other.

Comments:

2010-02-09T12:42:08Z

You consistently make great pictures for your posts. What do you use to make them?

2010-02-09T16:58:13Z

In this case, I wrote a Python script to generate POV-Ray source code.