Visualizing BFS as a spiral

It's a pretty obvious observation that the graphic conventions we use when illustrating mathematical objects can have a lot to do with how we think of them. The standard way the computer science textbooks draw trees is like a biological tree, but upside-down, with the root at the top and the leaves at the bottom:

When we view a tree in this way, the traversal order given by breadth-first search forms a geometric pattern that scans left-to-right across the vertices in a single level of the tree (conventionally, these vertices lie along a horizontal line), then the next level, and so on, much as one reads English text left-to-right and line-by-line. And this level-by-level ordering can be useful for conveying the idea that breadth-first search sorts vertices by their distances from the root.

But the breadth-first search algorithm itself, as it is usually described, does not progress level-by-level. Rather, it maintains a queue of open vertices that, in general, spans more than one level, and removes vertices from the tail of the queue and adds their unqueued neighbors to the head of the queue without regard for the boundaries between levels of the tree. The same properties, of performing the same steps at every vertex of a tree regardless of whether the vertex starts or ends a new level, and of not actually having any data that represents the boundaries between levels, is also true of an alternative BFS algorithm based on self-recursive iterators that I described a few years ago (this alternative algorithm typically uses much less space, but a constant factor more time, than a conventional BFS). The transition that these algorithms make from one level to the next is smooth, without the big discontinuities that the standard level-by-level visualization might make one think of.

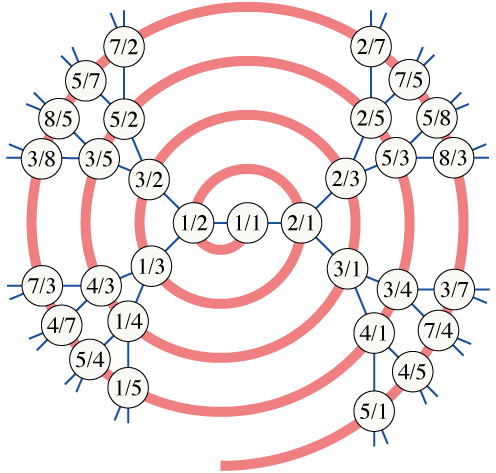

Last week, while working on the Wikipedia article on the Calkin–Wilf tree, I wanted to find a visual way of representing this smoothness. The Calkin–Wilf tree is a binary tree with \( 1/1 \) at the root, and where the children of \( a/b \) are \( a/(a+b) \) and \( (a+b)/b \); it contains every positive rational number exactly once, so one can list the positive rationals without duplication by performing a breadth-first search of this tree. And in fact this breadth-first search can be done by a simple formula, without any need for queues or recursion: the next number after \( q \) is \( 1/(2\lfloor q\rfloor+1-q) \). Notice, again, the lack of jumps in this sequence: the formula works the same no matter whether the next number belongs to the same level or is the start of another level in the tree. Eventually, I realized that if the tree were drawn radially, the BFS sequence could be visualized as a nice smooth spiral:

The same spiral layout can be used for any tree, and provides a nice graphical counterpart to the lack of jumps in the BFS algorithm. One can extend the metaphor: the head and tail of the BFS queue lie close together on two parallel tracks, and the BFS algorithm moves both of them in tandem while adding neighbors of the tail (on the inner track) to the head (on the outer track).

Some technical detail about the drawing: if one wants to preserve vertex spacing along the spiral, as the number of nodes per level grows exponentially, one should use a logarithmic spiral, but this will cause the lengths of the tree edges to grow quickly. Instead, I used an approximation to an Archimedean spiral formed by two sets of concentric semicircles with even and odd integer radii; the odd-radius semicircles lie in the bottom half of the drawing and the even radii lie in the top half. For the tree drawing, I used a style described (for concentric circles rather than spirals) in a paper I wrote with ![]() chouyu_31 in which one fixes the angles of the edges and then extends them to whatever length will make the vertices lie on the correct arm of the spiral. The angles were (as in that paper) chosen to maximize the sharpest angles of the drawing, while not allowing any two subtrees to turn back towards each other, but if I were to redraw this I might choose different angles that lead to a more uniform vertex placement.

chouyu_31 in which one fixes the angles of the edges and then extends them to whatever length will make the vertices lie on the correct arm of the spiral. The angles were (as in that paper) chosen to maximize the sharpest angles of the drawing, while not allowing any two subtrees to turn back towards each other, but if I were to redraw this I might choose different angles that lead to a more uniform vertex placement.

Comments:

2009-05-17T01:25:01Z

I really like this spiral illustration. It provides a lovely way to prove the rationals are countable.

But isn't there a typo here? The children of 4/3 (going from 1/1 -> 1/2 -> 1/3 -> 4/3) should be 7/3 and 4/7, shouldn't they?

2009-05-17T01:28:33Z

Oops, yes. Will fix.

2009-05-17T06:04:34Z

nice :)

2009-05-20T07:30:48Z

This is a very useful illustration to depict an elementary operation like BFS. Thanks for sharing!

2009-05-20T15:25:15Z

Very nice :)