Parts assembly and the burr puzzle antimatroid

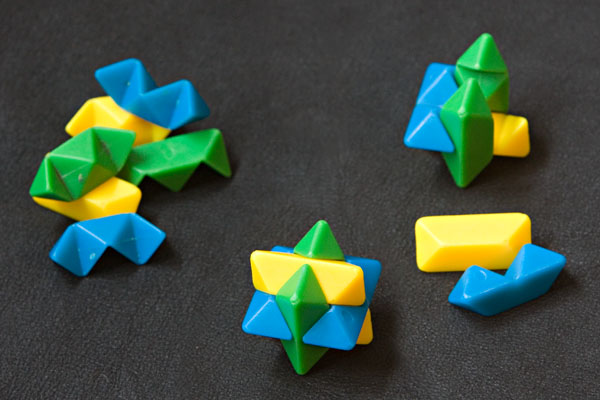

One of the toys on my desk is a small plastic burr puzzle, one of the simplest burr puzzles possible. It consists of six pieces, each in the shape of a square prism with beveled ends and notches in the middle. The bevels are there only for aesthetics, but the notches are important for allowing the pieces to fit together in the puzzle solution. One yellow piece is unnotched, one has two notches, both green pieces also have two notches, and both blue pieces have three notches. I've found a simple and easy-to-remember way to put it together: place the notched yellow piece down as a base with its notches up, stand the two green pieces on either side of it (with their bottom notches interlocking with the edges of the base), rest the two blue pieces in the notches of the base, and finally slip the unnotched yellow piece into the hole formed by the top notches of the standing green pieces. But then I started wondering: is that the only possible construction order? In how many other orders can I put the puzzle together, if I place the pieces into their final positions one piece at a time?

I eventually came up with the following state diagram. There are 24 different states the pieces can be in, starting from none of them being placed correctly and ending with them all in place, and it's easy enough to count paths from the starting position if one observes that all states with a given number of pieces have the same number of predecessors with one fewer piece: there are two paths to each two-piece state, six paths to each three-piece state, 18 paths to each four-piece state, and 36 paths to the penultimate and final states.

But it's all a bit messy looking. How can we be sure I haven't missed something? And is there some cleaner way of modeling this sort of state space?

Yes, there is. For one thing, any puzzler knows that it's easier to take things apart than to put them together, despite both processes resulting in the same sequences of moves. And when we take this puzzle apart, we can notice some patterns:

- The only piece that can be removed at first is the yellow unnotched one.

- The next piece to be removed must be one of the two blue three-notched pieces.

- The third piece to be removed cannot be the two-notch yellow base.

It turns out that these three rules are enough to determine the whole state space: every state formed by a removal sequence satisfying these rules is in the state diagram above, and I verified by manual manipulation (using the symmetries of the puzzle to reduce the number of possibilities) that each state transition in the diagram can actually be performed. The next idea that comes to mind is to model this system more simply by some sort of partial order (piece A can't be removed until piece B is) but that turns out not to work for this puzzle — by Birkhoff's representation theorem, if the removal ordering could be specified in this way by a partial order, the state space itself would be a distributive lattice, which isn't the case here. However, there's another, more general, way of describing this kind of state space, that applies not just to the burr puzzle but to any object that can be taken apart one piece at a time in this way. From Wikipedia:

In mathematics, an antimatroid is a formal system that describes processes in which a set is built up by including elements one at a time, and in which an element, once available for inclusion, remains available until it is included.

In this case, the set being built up is not the puzzle itself, but the set of removed pieces. And once a piece can be removed, it remains removable until it is actually removed: removing any other pieces only makes it easier to pull that piece away. So the family of states of this puzzle, and of many similar puzzles, can be described mathematically as an antimatroid. Antimatroids have two equivalent axiomatizations, one as a family of sets and one as a formal language. The family of sets is exactly the family of 24 states in the state diagram I depicted above (or rather, their set-theoretic complements). And the formal language is the set of sequences in which items can be removed, or (the reversals of) the set of 36 sequences in which the puzzle can be put together.

As I described in my paper “learning sequences” (for a completely different application involving automated assessment of student knowledge), antimatroids can often be described concisely by a generating set of basic words: sequences belonging to the formal language of the antimatroid (that is, removal sequences for the pieces of the puzzle) with the property that all possible states (sets of removed pieces) can be generated as unions of prefixes of these sequences. Naming the pieces y, Y, g, G, b, and B for their colors (with y being the unnotched yellow piece) we may generate the antimatroid for this puzzle by five such sequences: ybgYBG, ybGYBg, yBgYbG, yBGYbg, and ybBYgG. The algorithms in that paper will generate the whole state space efficiently from those five sequences. And if the whole state space is known, it's possible to find a minimal set of generators in polynomial time. But it still remains a topic of research to probe an unknown antimatroid (given say by a set membership oracle) to find its generators in less time than it would take to explore the whole state space.

Beyond puzzles, the same sort of problem of putting things together has been studied academically under the name of assembly planning: methods for figuring out how some compound object can be manufactured. But surprisingly, I haven't been able to find any research putting assembly planning together with antimatroid theory. It seems likely a fruitful area for deeper study.

Comments:

2008-12-03T12:18:47Z

It's a very nice article, thank you for your efforts in science popularization (and your efforts in improving Wikipedia. Lot of common people use it).

Despite my desire to learn more computer science and mathematics there are many things that I don't know yet, and this article gives me some keywords regarding topics that I can read more about.

I especially like how you try to list and explain some applications for some of the mathematical concepts you talk about; similar examples are a very important thing for everyone that isn't a professional mathematician.

You even offer ideas for possible other research: only especially good science popularization books like "Curious Naturalists" by Nikolaas Tinbergen share the same quality.

Unfortunately it seems that LiveJournal isn't the best place to post interesting technical articles, posts on other blog systems seem to attract more attention. My articles aren't as interesting as yours, but I have seen far worse stuff on other blog systems become much widely commented and known. LJ seems "Insular", as one person time ago said. Maybe LJ is mostly for personal stuff, like a personal diary.

2008-12-03T16:34:49Z

Thanks, leonardo.

In part I'm thinking of this sort of post as research itself more than popularization. I put it here rather than in the Wikipedia antimatroid article partly because it would unbalance that article, but also partly because I wasn't able to find anything in the literature describing the cinnection between assembly and antimatroids. So by the standards of Wikipedia, at least, it's original research, though by my own standards there's not yet enough new theory to publish as a research paper.

2008-12-03T22:27:00Z

the family of states of this puzzle, and of many similar puzzles, can be described mathematically as an antimatroid

This suggests it might be interesting to design burr-like puzzles which can't be described as antimatroids. Ones which have choices you can make that can't be undone, leading to different disassembly paths.

once a piece can be removed, it remains removable until it is actually removed: removing any other pieces only makes it easier to pull that piece away

This looks like an assumption that could be falsified in practice. For example, in a well-made tight-fitting wooden block puzzle there may be pieces that you can push towards the interior of the puzzle, but once pushed friction prevents them sliding back, and you can't grip them to pull them out again.

2008-12-03T22:29:12Z

The other aspect of these puzzles that is not modeled by this approach is that, for many of them (though not the one I used as an example) even removing a single piece can be very difficult, as it involves many small movements of the other pieces.