Analyzing Algorithm X

Today is Don Knuth's 70th birthday. Happy birthday, Don!

I could say a lot about my own relation with Knuth's work: as a freshman in college in 1981 I was hired to help typeset a book in TeX (The Handbook of Artificial Intelligence), my first published paper was on graph drawing using TeX, and my thesis work concerned dynamic programs closely related to the line-breaking algorithms in TeX. But I thought it might be appropriate, instead, to do something a little more technical.

Knuth was the first to use the phrase “analysis of algorithms,” at the 1970 ICM in Nice. He popularized and extended O-notation (previously used in functional analysis) as an essential tool for algorithm analysis. And, his Art of Computer Programming set the standards for the field and is still well worth reading today. So, it seems a little presumptuous for me to analyze one of Knuth's own algorithms. I set out only with the goal of understanding one of his many papers, “Dancing Links,” which concerns a backtracking algorithm for an NP-complete problem, a subject of some interest to me. But, as so often, the problem took over and wouldn't let me go until I'd found something to add to it. Several times I thought I'd reached the end of the analysis, only to discover another refinement that kept it going deeper, until eventually this grew from a blog post to something resembling the outline of a full paper. I imagine Knuth is familiar with this process, on a much larger scale, as his Art of Computer Programming also grew far larger than he originally envisioned. Regardless, here is my analysis.

The Exact Cover Problem

The problem studied in Knuth's paper is exact cover: given a family of sets, find a subfamily of disjoint sets with the same union as the whole family. For instance, suppose the input family consists of all the vertices and edges of a four-vertex cycle graph: \[ \bigl\{ \{ a \}, \{ b \}, \{ c \}, \{ d \}, \{ a, b \}, \{ b, c \}, \{ c, d \}, \{ d, a \} \bigr\}. \]Then these eight sets combine to form seven different exact covers:

- \( \bigl\{ \{ a \}, \{ b \}, \{ c \}, \{ d \}\bigr\} \)

- \( \bigl\{ \{ a, b \}, \{ c \}, \{ d \}\bigr\} \)

- \( \bigl\{ \{ a \}, \{ b, c \}, \{ d \}\bigr\} \)

- \( \bigl\{ \{ a \}, \{ b \}, \{ c, d \}\bigr\} \)

- \( \bigl\{ \{ b \}, \{ c \}, \{ d, a \}\bigr\} \)

- \( \bigl\{ \{ a, b \}, \{ c, d \}\bigr\} \)

- \( \bigl\{ \{ b, c \}, \{ d, a \}\bigr\} \)

Exact cover is one of the 21 NP-complete problems in Karp's 1972 “Reducibility Among Combinatorial Problems,” a paper that forms (together with Cook's theorem) the foundation of NP-completeness theory. Knuth describes applications of exact cover in finding polyomino tilings, using sets of the cells that can be covered by each possible placement of each polyomino. The seven exact covers above can be interpreted in this way as the tilings of a \( 2\times 2 \) square by monominos and dominos:

Sudoku puzzles can also be expressed as exact cover problems, in which there is one element for each cell, one element for each combination of a digit and a group of nine cells, and one set for each combination of a digit and a single cell. Another standard combinatorial problem, the eight queens problem, is not quite an exact cover problem directly (the selected queen placements must cover each row and column of a chessboard but only cover 16 of the 30 diagonals) but can be made into one by adding seven additional “virtual pieces” that may each cover two perpendicular diagonals but no rows or columns. If all sets in an exact cover instance have exactly two elements (as for instance, in the eight rooks problem, in which the set representing each rook placement contains a single row and a single column), the problem becomes that of perfect matching, a polynomially-solvable but nontrivial special case.

Algorithm X

The algorithmic content of Knuth's paper involves a backtracking algorithm that Knuth calls “Algorithm X,” and some techniques for implementing Algorithm X efficiently using doubly linked lists (where the “dancing links” of the title come in). Algorithm X can be defined very simply, if one skips over such details; it is a recursive search procedure that takes as arguments a set \( U \) of elements and a family \( F \) of subsets of \( U \) and performs the following steps.

- Algorithm X:

- If \( U \) is empty, return the empty cover

- Choose arbitrarily an element \( x \) of \( U \)

- For each set \( S_i \) in \( F \) that contains \( x \):

- Form a set family \( F' \) consisting of the sets in \( F \) that are disjoint from \( S_i \)

- Solve recursively the exact cover problem \( (U\setminus S_i,F') \)

- If a solution is found, add \( S_i \) to the solution and return it

Different choices of the “pivot” \( x \) may lead to different running times — for instance, if one can choose a pivot that is not contained in any of the sets, it is preferably to do so, because then the algorithm will immediately backtrack rather than fruitlessly searching unsolvable subproblems. But what can we say more rigorously about the worst case performance of Algorithm X? If \( n \) is the number of sets in the input family, what function \( f(n) \) describes the running time of the algorithm? Because of the way the dancing links implementation reduces the input size of the subproblems in the recursive calls, the time per call at the bottommost levels of the recursion (where most of the work happens) will be constant, so we may equivalently ask how many recursive calls are made.

Algorithm X may easily be modified to find, not just one exact cover, but all of them, so one possible lower bound on its performance is provided by the maximum number of different exact covers in any instance. For instance, an exact cover instance formed from \( k \) disjoint copies of the \( 2\times 2 \)-square example has \( 7^k \) different solutions, formed from \( n=8k \) input sets, so (as a function of \( n \)) the number of exact covers is \( 7^{n/8}\approx 1.27537^n \). Any version of Algorithm X that lists all covers must take at least this much time.

Upper bounds for Algorithm X

What about upper bounds? Let \( C \) denote the subfamily of sets in \( F \) that contain the chosen element \( x \); then the algorithm will perform |\( C \)| recursive calls, but, in each of these calls the size of the set family \( F' \) is at most \( n-|C| \), because \( F' \) and \( C \) must be disjoint. For example, it may perform two recursive calls of size at most \( n-2 \), three recursive calls of size at most \( n-3 \), four recursive calls of size at most \( n-4 \), etc. The worst of these cases is the one with three recursive calls, leading to a time bound of \( O(3^{n/3})\approx 1.44225^n \). Therefore, even the stupidest version of Algorithm X, one that avoids any chance to backtrack and always chooses its pivots in such a way as to maximize its running time, takes at most \( O(3^{n/3} \) time. This bound is tight as may be seen for instances consisting of many disjoint copies of the set system \[ \bigl\{ \{ a, b \}, \{ a, c \}, \{ a, d \} \bigr\} \] and for an algorithm that always pivots on an element contained in as many sets as possible. It is also a tight bound on the number of solutions for a generalization of exact cover in which \( F \) is allowed to include multiple copies of the same set; for instance, if one tiles a rectangle by monominos of three different colors, there are \( 3^{n/3} \) different solutions.

For exact cover itself, one can do better using Knuth's suggestion of choosing a pivot element that is contained in as few sets as possible. Pivots contained in no sets lead to immediate backtracking, and pivots contained in a single set lead to a smaller subproblem with no branching, so we need only worry about pivots contained in two or more sets. Before diving into case analysis, it will be helpful to have a lemma analyzing the sizes of the subproblems the algorithm may encounter.

Lemma 1. Suppose that Algorithm X chooses a pivot \( x \), contained in sets \( S_i, i = 1, 2,\dots k \), and that no other element is contained in fewer sets. Let \( \mathbf{s}=(s_1,s_2,\dots s_k) \), where \( s_i \) is the number of sets in \( F \) that have a nonempty intersection with \( S_i \) (including \( S_i \) itself). Suppose also that the ordering of the subscripts is chosen so that the vector \( \mathbf{s} \) is in sorted order from smaller values to larger values. Then either there exists an \( i \) such that \( s_i\ge k+i \), or each \( s_i=k+i-1 \). In the latter case, the sets \( S_i \) are totally ordered by inclusion.

Proof sketch: We show by induction that, if the first \( i \) components of \( \mathbf{s} \) are equal to \( k+i \), then the first \( i \) sets are totally ordered by inclusion and each are subsets of all remaining sets, and further that in this case \( s_i+1\ge k+i+1 \). As a base case, the total ordering holds vacuously for \( i=0 \), and in this case the lower bound \( s_1\ge k \) holds as \( S_1 \) must intersect each of the \( k \) sets \( S_i \). In the inductive case, suppose that all sets up to but not including \( S_i \) have the minimum size allowed by the lemma. Then by the induction hypothesis, \( S_i \) is a superset of \( S_{i-1} \), and has a nonempty intersection with all of the \( k+i-2 \) sets that \( S_{i-1} \) intersects. Because it is a superset, \( Y = S_i\setminus S_{i-1} \) is nonempty; each element \( y \) in \( Y \) must be contained in at least \( k \) sets of the set system \( F \), none of which can be among the \( i-1 \) sets earlier in the sequence. At most \( k-1 \) of the sets containing \( y \) can be among the \( k+i-2 \) sets already known to intersect \( S_i \), for the \( i-1 \) sets occurring earlier in the sequence do not contain \( y \). Thus, there must be at least one additional set containing \( y \). If there is exactly one additional set \( T_i \) that contains each \( y \) in \( Y \), then \( Y \) is contained in all subsequent sets \( S_j \) for \( j\gt i \), and \( s_i\ge k+i-1 \); otherwise, there are two or more additional sets intersecting with \( Y \), and \( s_i\ge k+i \). In either case the induction hypothesis holds and the lemma is proven.

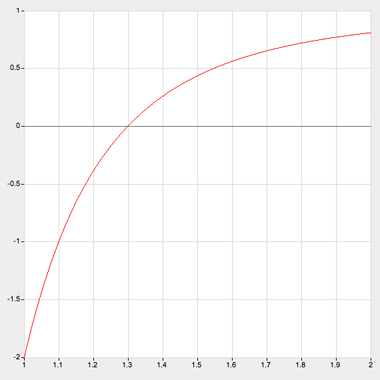

Using this lemma, we may proceed to analyze cases. In general, each case will lead to a recurrence of the type \( T(n)=\sum T(n-s_i) \), which is solved as \( \kappa^n \) where \( \kappa \) is a root of the function \( 1-\sum\kappa^{-s_i} \). A numerical approximation to \( \kappa \) may easily be found by binary search, or by more sophisticated numerical search procedures, as this function is negative for \( \kappa \) between one and the desired root, and positive for all \( \kappa \) larger than the root. For instance, the graph of the function \( 1-1/\kappa^3-2/\kappa^5 \) shown below (created with Walter Zorn's function grapher) shows how well behaved this function is for \( \mathbf{s}=(3,5,5) \). The overall worst-case behavior of an algorithm of this type can be bounded as the maximum among the solutions of the different recurrences arising from the different cases. We need only determine the minimal vectors \( \mathbf{s} \) allowable by the lemma, search for the roots corresponding to each vector, and choose the maximum value κ among the different roots found by these searches.

Thus, for Algorithm X, with the pivot rule in which the algorithm chooses \( x \) to be contained in as few sets as possible and using Lemma 1 to bound \( \mathbf{s} \), we have the following cases.

If \( x \) is contained in two sets, \( \mathbf{s} \) must equal or be componentwise larger than \( (2,3) \). We get a recurrence \( T(n)\ge T(n-2)+T(n-3) \), the solution of which is approximately \( 1.32472^n \), where the base of the exponential is the plastic number.

If \( x \) is contained in three sets, \( \mathbf{s} \) must equal or be componentwise larger than \( (3,4,5) \) or \( (4,4,4) \). We get two possible recurrences, \( T(n)\ge T(n-3)+T(n-4)+T(n-5) \) or \( T(n)\ge 3T(n-4) \). The solution to the former is again \( 1.32472^n \), while the solution to the latter is approximately \( 1.31607^n \).

If \( x \) is contained in four sets, \( \mathbf{s} \) must equal or be componentwise larger than \( (4,5,6,7) \), \( (5,5,5,5) \), or \( (4,6,6,6) \). The three resulting recurrences solve to \( 1.29647^n \), \( 1.31951^n \), and \( 1.29294^n \).

If \( x \) is contained in five sets, \( \mathbf{s} \) must equal or be componentwise larger than \( (5,6,7,8,9) \), \( (6,6,6,6,6) \), \( (5,7,7,7,7) \), or \( (5,6,8,8,8) \). The four resulting recurrences solve to \( 1.26859^n \), \( 1.30766^n \), \( 1.28032^n \), and \( 1.26696^n \).

If \( x \) is contained in six or more sets, \( \mathbf{s} \) must be componentwise larger than the vector \( (k,k+1,k+1,k+2,\dots) \). The worst case for vectors of this type occurs when \( k \) equals six, for which the solution is \( 1.30077^n \).

However, this is not the end of the analysis. Consider the two worst cases, branches with size reduction vectors \( (2,3) \) and \( (3,4,5) \). In all but the last recursive subproblem in each of these cases, the analysis of Lemma 1 tells us that there must be an element \( y \) contained only in a single set \( T_i \) of the remaining subproblem. The next step of Algorithm X will be to pivot on \( y \) and eliminate this set without performing any more branching. Thus, effectively, these two cases lead to \( (3,3) \) and \( (4,5,5) \) reductions, much better than the analysis above. The worst remaining case, once the \( (2,3) \) and \( (3,4,5) \) cases are eliminated and \( (2,4) \), \( (3,3) \), \( (3,4,6) \), \( (3,5,5) \), and \( (4,4,5) \) included in their place, is a \( (5,5,5,5) \) branch. Therefore, as this analysis shows, in the worst case, Algorithm X takes time \( O(4^{n/5})\approx O(1.31951^n) \).

Reducing the instance size without branching

Although Algorithm X already performs well on chains such as the \( (2,3) \) and \( (3,4,5) \) cases discussed above, we can do a little better. In this case, it turns out that the problem size may be reduced for free without doing any branching. However the price for this improvement is that generating all solutions, rather than just a single solution, becomes more awkward.

Suppose the sets \( S_i \) containing the pivot \( x \) have the property that the intersection of any two such sets other than \( S_1 \) is a proper superset of \( S_1 \); this property holds, for instance, in the case of a chain. We call a family of sets with this property a \( nest \). Rather than pivoting on \( x \), perform the following transformation: replace \( U \) with \( U\setminus S_1 \), remove \( S_1 \) from \( F \), and also remove from \( F \) any set that intersects \( S_1 \) but does not contain \( x \). Replace each other set \( S_i \) containing \( x \) with the set \( S_i\setminus S_1 \). This modified problem has at least one fewer set than the original. I claim that its exact covers are in one-to-one correspondence with the exact covers of the original problem. For, in one direction, any solution to the original problem must contain exactly one set in the nest, and corresponds in the obvious way to a solution of the modified problem. In the other direction, as the modified sets \( S_i\setminus S_1 \) continue to intersect pairwise, at most one of them can be included in any exact cover. If one of them, \( S_i\setminus S_1 \), is included in some exact cover, then replacing \( S_i\setminus S_1 \) with \( S_i \) forms an exact cover of the original problem. And if none of them are included in some exact cover, then adding \( S_1 \) forms an exact cover of the original problem.

However, there is a catch. Suppose that we perform this transformation, replacing some \( S_i \) by \( S_i\setminus S_1 \), but suppose also that \( S_i\setminus S_1 \) already exists as a separate set in the family. What do we do? The one-for-one correspondence of solutions of the reduced problem and solutions of the original problem only holds if we allow multiple copies of the same set in our reduced problem, which prevents us from applying Lemma 1. If we only care about finding a single solution, though, there is no problem: simply keep one copy of the duplicate set (it doesn't matter which one). If we are interested in the number of solutions, rather than a list of solutions, we may keep an integer multiplicity on each input set, add together the numbers of duplicate sets, and multiply together the numbers of the sets used in any solution. And if we really wish to list all solutions, we may associate with each set in any reduced instance a list of the larger sets it comes from, so that, once we have found a solution to the reduced problem we may produce from it a list of all corresponding solutions in the original problem.

If a search algorithm for the exact cover problem uses this transformation to reduce the problem size whenever a nest is detected, instead of branching, the worst remaining cases turn out to be those in which \( \mathbf{s} \) is \( (4,4,4) \) or \( (5,5,5,5) \). But in those cases, also, it is possible to simplify the problem without branching, using the following lemma.

Lemma 2. Suppose that all elements of \( U \) are contained in \( k \) or more sets of \( F \) (for \( k \) ≥ 3), that some element \( x \) is contained in exactly \( k \) sets of \( F \), and that each of the sets of \( F \) containing \( x \) has a nonempty intersection with at least \( k+1 \) sets (including itself). Then either there is a set \( Y \) that does not contain \( x \) but intersects all sets containing \( x \) in \( F \), or the sum of the components of the vector \( \mathbf{s} \) is at least \( k^2+2k-2 \).

\( Proof sketch: \) If all sets in \( F \) that contain \( x \) intersect \( k \) + 2 or more other sets, the sum of components of \( \mathbf{s} \) is at least \( k^2+2k \) and the lemma is proved; otherwise, let \( A \) be a set in \( F \) that contains \( x \) and intersects exactly \( k+1 \) sets in \( F \). Since \( A \) intersects more sets than the \( k \) sets containing \( x \), there must be some element \( y \) in \( A \), and some set \( Y \) containing \( y \), such that \( Y \) does not contain \( x \). If \( Y \) intersects all sets in \( F \) that contain \( x \), the lemma is proved; otherwise, \( y \) must be contained in exactly \( k \) sets, namely, \( Y \) itself, and all but one of the \( k \) sets that contain \( x \). Let \( B \) be the set in \( F \) that contains \( x \) but does not contain \( y \) nor any other element of \( Y \). Since \( B \) intersects at least \( k+1 \) sets in \( F \), there must be an element \( z \) in \( B \), and a set \( Z \) containing \( z \) but not containing \( x \). Each intersection between sets containing \( x \) contributes one unit towards the total of \( \mathbf{s} \), for a total contribution of \( k^2 \) units, and the intersections between \( Y \) and the sets other than \( B \) contribute an additional \( k-1 \) units. Each of the \( k \) sets containing \( z \), other than \( B \) itself, contributes an additional unit either for its intersection with \( B \) or its intersection with \( Z \). Thus, the total is as stated in the lemma.

Note that, if the problem instance includes a set \( Y \) that intersects every set containing \( x \), as described as one of the possible cases in the statement of the lemma, then \( Y \) cannot be part of any exact cover, as including it in a cover would prevent \( x \) from being covered.

Using these two simplification rules, we define Algorithm Y as follows:

- Algorithm Y:

- If \( U \) is empty, return the empty cover

- Choose arbitrarily an element \( x \) of \( U \)

- If some set \( Y \) does not contain \( x \) but intersects all sets containing \( x \):

- Remove \( Y \) from \( F \)

- Solve the resulting smaller instance

- Else if the sets containing \( x \) form a nonempty nest:

- Form the modified instance \( (U',F') \) as described above

- Solve recursively the modified instance

- If a solution is found, form the corresponding solution to the original problem as described above and return it.

- Else, for each set \( S_i \) in \( F \) that contains \( x \):

- Form a set family \( F' \) consisting of the sets in \( F \) that are disjoint from \( S_i \)

- Solve recursively the exact cover problem \( (U\setminus S_i, F') \)

- If a solution is found, add \( S_i \) to the solution and return it

As an example, consider applying Algorithm Y to the example instance we started with, with eight sets, four elements, and seven exact covers. The recursion tree has only one multiway branch, at the outermost level of recursion; each successive call after that leads to an instance of the nesting rule, until the problem reduces to instances with a single set:

The \( 7^{n/8} \) lower bound no longer applies to this algorithm, because different exact covers do not necessarily lead to different leaves of the recursion tree.

Preliminary Analysis of Algorithm Y

As with Algorithm X, we may analyze algorithm Y (with the pivot rule that chooses \( x \) to have as few sets containing it as possible) using the lemmas to bound the vectors \( \mathbf{s} \) of subproblem size reductions. Although the algorithm itself is still relatively simple, its analysis is complex and involves many cases.

If the algorithm branches on \( x \), and \( x \) is contained in two sets of \( F \), \( \mathbf{s} \) must equal or be componentwise larger than \( (3,3) \). We get a recurrence \( T(n)\ge 2T(n-3) \), the solution of which is \( 2^{n/3}\approx 1.25992^n \).

If the algorithm branches on \( x \), and \( x \) is contained in three sets of \( F \), \( \mathbf{s} \) must equal or be componentwise larger than either \( (3,5,5) \) or \( (4,4,5) \): as shown below, Lemma 1 rules out \( (3,4,5) \) and smaller vectors, while Lemma 2 rules out \( (4,4,4) \). The \( (3,5,5) \) case gives us a recurrence solving to approximately \( 1.29803^n \), while the \( (4,4,5) \) case solves to approximately \( 1.29065^n \).

If the algorithm branches on \( x \), and \( x \) is contained in four sets of \( F \), \( \mathbf{s} \) must equal or be componentwise larger than \( (4,5,7,7) \), \( (4,6,6,6) \), \( (5,5,6,6) \), or \( (5,5,5,7) \). The four resulting recurrences solve to approximately \( 1.28449^n \), \( 1.29294^n \), \( 1.28854^n \), and \( 1.29193^n \) respectively.

If the algorithm branches on \( x \), and \( x \) is contained in five sets of \( F \), \( \mathbf{s} \) must equal or be componentwise larger than \( (5,6,7,9,9) \), \( (5,6,8,8,8) \), \( (5,7,7,7,7) \), \( (6,6,7,7,7) \), \( (6,6,6,7,8) \), or \( (6,6,6,6,9) \). The six resulting recurrences solve to approximately \( 1.26246^n \), \( 1.26696^n \), \( 1.28032^n \), \( 1.27757^n \), \( 1.27971^n \), and \( 1.28360^n \) respectively.

If the algorithm branches on \( x \), and \( x \) is contained in six sets of \( F \), \( \mathbf{s} \) must equal or be componentwise larger than \( (6,7,8,9,10,12) \), \( (6,7,8,9,11,11) \), \( (6,7,8,10,10,10) \), \( (6,7,9,9,9,9) \), \( (6,8,8,8,8,8) \), \( (7,7,8,8,8,8) \), \( (7,7,7,8,8,9) \), \( (7,7,7,7,9,9) \), \( (7,7,7,7,8,10) \), or \( (7,7,7,7,7,11) \). The ten resulting recurrences solve to approximately \( 1.24189^n \), \( 1.24121^n \), \( 1.24386^n \), \( 1.25139^n \), \( 1.26610^n \), \( 1.26431^n \), \( 1.26572^n \), \( 1.26715^n \), \( 1.26829^n \), and \( 1.27181^n \) respectively.

If the algorithm branches on \( x \), and \( x \) is contained in seven or more sets, \( \mathbf{s} \) must be componentwise larger than the vector \( (k,k+1,k+1,k+1,\dots) \). The worst case for vectors of this type occurs when k equals seven, for which the solution is \( 1.28168^n \).

Thus, Algorithm Y with the pivot rule that chooses the pivot \( x \) with the smallest number of containing sets runs, in the worst case, in time \( O(1.29803^n) \). The worst case is the \( (3,5,5) \) split, which occurs arbitrarily often in our example of monomino and domino tilings of disjoint \( 2\times 2 \) squares.

Matchings in Cycle Graphs

Now that our preliminary analysis has identified the \( (3,5,5) \) branch as problematic, let us make one additional refinement to the pivot rule for Algorithm Y. As before, we choose a pivot \( x \) that is covered by as few sets as possible. But, in order to avoid the \( (3,5,5) \) branch, we break ties in choosing the pivot in favor of pivots that do not form this split. That is, if the pivots we may choose among are contained in exactly three sets each, we only choose a \( (3,5,5) \) branch in the situation in which all three-set pivots lead to the same vector of subproblem size reductions.

Suppose that, despite our attempts to avoid it, the algorithm still performs a \( (3,5,5) \) branch. What can we say about the structure of the instance in this case? To simplify the discussion (although the algorithm does not perform this simplification) we assume that no two elements are contained in exactly the same collection of sets. Then, in order to form a \( (3,5,5) \) branch, the three sets containing the pivot \( x \) must be of the form \( \{ x \}, \{ x, y \} \), and \( \{ x, z \} \) for some elements \( y \) and \( z \). In addition, \( y \) and \( z \) must themselves each be contained in three sets, and similarly form pivots that lead to \( (3,5,5) \) branches.

We may draw a graph in which the vertices are pivots of (3,5,5) branches, and the edges of the graph are sets of \( F \) that contain two such pivots. By the analysis above, this graph has exactly two edges at every vertex; that is, it is a collection of disjoint cycles.

Now, consider what happens once Algorithm Y chooses a pivot within one of these cycles. In the next step, in each of the three recursive calls after the \( (3,5,5) \) branch, the neighboring vertices in the cycle will be covered by exactly two sets of the instance: a singleton set containing only the vertex, and one of the two edges that were in the graph before the pivot was performed. Thus, the Algorithm will proceed to reduce the instance by applying the nesting rule, without performing any more branching. This reduction continues until the entire cycle has been removed from the instance. Thus, for the cost of three recursive calls, the algorithm reduces the problem not only by the three or five sets that it removes at the time of the \( (3,5,5) \) branch, but by the number of sets included in the whole cycle. The worst case occurs for the smallest possible cycle, a triangle, which acts effectively like a \( (6,6,6) \) branch and leads to a recurrence with an \( O(3^{n/6})\approx O(1.20094^n) \) solution, much smaller than those arising from other cases in the algorithm. Thus, we may eliminate the \( (3,5,5) \) branch from our case analysis and consider the other cases instead.

The next most time-consuming cases in our preliminary analysis are the cases in which the branches of the algorithm are described by the vectors \( (4,4,5) \), \( (4,6,6,6) \), \( (5,5,5,7) \), and \( (5,5,6,6) \). However, additional analysis (left to the exercises) shows that for each of these vectors, either a branch with that vector is not possible at all or, like the \( (3,5,5) \) case, a branch of this type leads to additional simplifications in successive steps of the algorithm. It turns out that the worst case that we cannot yet handle in this way is a \( (4,5,7,7) \) branch, which leads to a recurrence with the solution \( O(1.28449^n) \).

Thus, in the worst case, with our \( (3,5,5) \)-avoiding pivot rule, Algorithm Y runs in time \( O(1.28449^n) \).

Conclusions

We may draw the following conclusions from our analysis:

Algorithm X is pretty good already, especially if one wants to list all solutions to an exact cover problem. For finding a single solution or counting solutions, Algorithm Y may be even better.

Analysis of algorithms may be helpful not just for understanding the performance of an algorithm but also for drawing attention to the areas of the algorithm in which more refinement can be most helpful.

In exponential backtracking algorithms of this type, it is common to see complex case analysis of the type we have seen here. But it is not always necessary for this case analysis to be reflected in the algorithm: Algorithm X is very simple, and Algorithm Y only incorporates a few simple and general rules for simplifying its instances. The mess of cases arises only in their analysis.

The analysis of Algorithm X also provides an algorithmic proof that any system of \( n \) sets has at most \( 4^{n/5} \) exact covers. Although this upper bound for the maximum number of exact covers does not match the \( 7^{n/8} \) lower bound coming from the tilings of \( 2\times 2 \) squares, the gap between the two bounds is not large.

Exercises

What Knuth tribute would be complete without exercises? The parenthesized numbers are my estimate of the difficulty of the problem, on Knuth's familiar scale.

\( (10) \) Trace through the execution of Algorithm Y on the \( 2\times 2 \) square example, as in the figure, but showing additionally the number of ways each set in each instance may be derived from its parent instance. Use these numbers to count the number of solutions to the original problem found in each branch of the execution.

\( (20) \) In some exact cover instances, such as those for Sudoku puzzles, we may be guaranteed that there exists exactly one solution. What additional simplification does this guarantee allow in the nesting rule of Algorithm Y?

\( (25) \) Suppose that Algorithm Y, with a pivot rule that always chooses the least covered pivot, performs a \( (4,4,5) \) branch. Show that, in two of the three recursive calls, there exists a pivot covered by only a single set. Write down a recurrence describing this case, taking into account the treatment of this single-set pivot, and find the asymptotic solution to this recurrence.

\( (25) \) Suppose that Algorithm Y, with a pivot rule that always chooses the least covered pivot, performs a \( (4,6,6,6) \) branch. Show that, in this case, at least two of the recursive calls have an uncovered element and will immediately backtrack. Write down a recurrence describing this case, taking into account the two backtracking calls, and find the asymptotic solution to this recurrence.

\( (25) \) Prove that Algorithm Y, with a pivot rule that always chooses the least covered pivot, cannot perform a \( (5,5,5,7) \) branch.

\( (25) \) Prove that Algorithm Y, with a pivot rule that always chooses the least covered pivot, cannot perform a \( (5,5,6,6) \) branch.

\( (20) \) Once the \( (3,5,5) \), \( (4,4,5) \), \( (4,6,6,6) \), \( (5,5,5,7) \), and \( (5,5,6,6) \) branches are eliminated for Algorithm Y, what additional possibilities for \( \mathbf{s} \) must be added to the list of minimal non-eliminated branches? Compute numerically the asymptotic solution to each of these possibilities and show that they are not worse than the \( (4,5,7,7) \) branch identified as the worst case in our analysis.

\( (35) \) Implement Algorithm X and Algorithm Y, and test them on examples. Does the additional complexity of Algorithm Y lead to improved performance in practice?

\( (25) \) Describe an additional simplification rule that can be applied to exact cover instances in which two elements are each contained in only two sets, one of which is the same for both elements. How should this rule handle multiplicities of sets?

\( (30) \) Observe that, if an instance \( (U,F) \) of Algorithm Y with \( t \) sets leads to an execution in which \( k \) leaves of the recursion tree have valid solutions, then running Algorithm Y on instances formed by \( n/t \) disjoint copies of \( (U,F) \) takes time \( \Omega(k^{n/t}) \), as long as the prioritization of pivots within each copy remains the same. Use this principle to find good lower bounds for Algorithm Y.

\( (40) \) find a tight (\( \Theta \)-notation) worst-case time bound for Algorithm X, closing the gap between its \( \Omega(7^{n/8}) \) lower bound and its \( O(4^{n/5}) \) upper bound.

\( (45) \) Find an exact formula (without \( O \)-notation!) for the maximum number of exact covers any family of \( n \) distinct sets can have, as a function of \( n \).

Comments:

2008-01-11T01:33:46Z

i was just wondering what icm stands for. could not find it on dblp.