Inverted permutohedra

The \( n! \) permutations of the vector \( (1,2,3,\dots,n) \) lie on a hyperplane, so their convex hull forms an \( (n-1) \)-dimensional shape, known as the permutohedron. E.g., the three-dimensional permutohedron, representing the permutations on four items, is below.

Two permutations are connected by an edge in this shape if they differ by swapping two items that differ in value by one. The graph of vertices and edges of this shape is one of the standard examples of partial cubes, although it doesn't look very cubical in this form.

But now imagine the same graph, rearranged by moving every permutation to its inverse. What do you get?

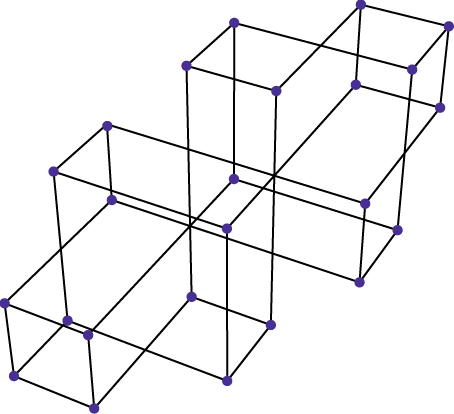

Here's a picture, made a little clearer without changing the connection pattern by transforming the shape linearly: instead of the symmetric placement of permutohedron vertices shown above, I used prefix-sum coordinates, so e.g. the permutation \( (3,1,4,2,6,5) \) would be placed at coordinates \( (3,3+1,3+1+4,3+1+4+2,3+1+4+2+6) \), omitting the \( n \)th coordinate as it is always \( n(n+1)/2 \). I then rearranged the graph as described above, and got the following picture:

Now two permutations are connected by an edge if their prefix-sum representations differ in a single coordinate; that is, if they differ by swapping two items that differ in position by one. So, unlike the usual permutohedron, the edges fall into \( n-1 \) parallel classes, which in the prefix-sum representation are parallel to the coordinate axes.

The lower left vertex in the image corresponds to the sorted permutation \( (1,2,3,\dots) \) and the upper right vertex corresponds to the reverse-sorted permutation \( (\dots,3,2,1) \). A monotone path from lower left to upper right corresponds to a circular sequence of permutations (or actually, half of such a sequence). Each such path has the same number of edges overall, but paths may vary by how many of their edges go in each of the \( n-1 \) possible directions. It would be very interesting to get good bounds on the maximum number of times edges of one direction can be used in a path (that is, how many swaps in a circular sequence of permutations can occur at the same position), as this is a form of the famous k-set problem from discrete geometry.

There also seems to be some interesting structure in the sequence of lower-dimensional cross-sections of these shapes...