Single-digit Sudoku rules

I had thought the "digit" rule of my Sudoku program was a non-backtracking equivalent of nishio. Turns out not.

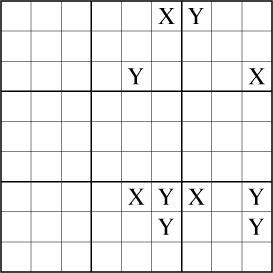

Both rules have the same purpose: looking only at the cells where a single digit may be placed, determine which of those cells can possibly be used in a solution to the puzzle, and eliminate the others. For example, suppose that (by other deduction rules) we have limited the locations for the digit 7 in four squares of a puzzle to the X's and Y's shown in the following diagram (with the 7's in the other five squares placed in positions compatible with these locations):

If we place a 7 at the X at bottom left, it eliminates the Y at top left, forcing the 7 in that square to be placed at X as well, and so on. By a sequence of similar deductions we find that if any 7 is placed on an X, all four squares must have their 7's placed at X's. But the X's do not give a consistent solution to the puzzle (the bottom two are on the same row), so none of the 7's can be placed on any X. We can deduce that the 7's may only be placed at the positions marked Y, and in particular we can immediately place 7's at the Y's in the top two squares. We would like a deduction rule that quickly comes to this conclusion.

Perfect Matching

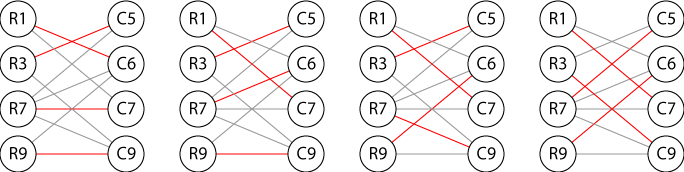

The way my program attempts to make deductions like this involves perfect matching in graphs. It forms a bipartite graph, having 18 vertices, one for each row and one for each column of the puzzle. We connect vertices Ri and Cj by an edge in the graph, exactly when cell RiCj is a potential placement for the digit 7. Perfect matchings in this graph correspond to placements of 7's throughout the puzzle that cover each row and each column exactly once. By finding a single perfect matching then performing strong connectivity analysis, we can quickly identify the edges that do not belong to a perfect matching, and eliminate the corresponding cells as potential placements for the digit 7.

In the example above, considering only the rows and columns involved in the marked cells, we get a graph with four perfect matchings:

Unfortunately, only two of the matchings correspond to possible solutions of the puzzle. The other two have two 7's in two of the four squares and none in the other two squares, leading to invalid solutions. This is not detected by the matching algorithm because it only considers rows and columns, not squares. So my program's rule fails to eliminate the X's as potential placements for the digit 7.

Nishio

Nishio, on the other hand, handles this example easily. In this rule, which is controversial because it has more the flavor of trial-and-error than deductive reasoning, one tests each potential position for the digit separately. To test a position, we try placing the digit there, then expands the consequences of that placement until a contradiction is reached or a complete solution is found. In its most simple form, "expand the consequences" means, eliminate positions that conflict with a placed digit, and place a digit whenever it is the only remaining position in its row, column, or square, and "contradiction" means that we have placed two digits in the same row, column, or square, or that we have eliminated all positions in some row, column, or square. If a contradiction is reached, we eliminate the original placement as a potential location for that digit. When I am solving a Sudoku by hand and use this rule, I sometimes use more sophisticated deductions in the expansion phase: if a digit's placements in a square are limited to a single row or column, eliminate placements in the same row or column in other squares, and if a digit's placements in a row or column are limited to a single square, eliminate placements in the same square in other rows or columns.

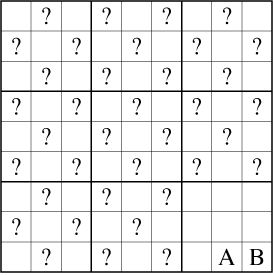

However, nishio is not omniscient. For instance, suppose that the locations for the digit 4 in a puzzle have been limited to the marked cells below:

Can we place 4 at A or B? As it turns out, B can be part of a valid solution. However, if we place 4 at A, the remaining cells can be decomposed into two independent blocks, one with five columns and four rows, and the other with three columns and four rows; it is impossible to fill all the rows and columns of both blocks, so the placement at A should be eliminated. The matching rule can detect this inconsistency, but nishio can't.

Other Single Digit Rules

One of the simpler rules my program implements is the one described above as part of the nishio expansion phase: if a digit's placements in a square are limited to a single row or column, my program eliminates placements in the same row or column in other squares, and if a digit's placements in a row or column are limited to a single square, my program eliminates placements in the same square in other rows or columns. My program labels this the "align" rule. Because this rule involves squares as well as rows and columns, it can make deductions that my perfect matching based rule would be unable to make. Another way to implement something resembling the align rule would be to look for perfect matchings in a graph with vertices corresponding to rows and squares (or columns and squares) instead of rows and columns; for 9x9 Sudoku this would merely make the rule more complicated without increasing its deductive power, but this matching based idea would be more powerful than the align rule for larger variants of Sudoku.

Some other well known Sudoku rules such as the X-wing and Swordfish also consider only a single digit at a time. In the X-wing rule, if the cells in two rows that can contain a digit are restricted to two columns, we can eliminate all other potential placements for that digit in those columns. The Swordfish rule is similar, but for certain combinations of positions in three rows and columns. Any deduction made by these rules will also be made by my perfect matching based rule, so my program doesn't implement them separately. These rules are also subsumed by nishio but maybe worth including in a nishio-based solver anyway, since they should be faster and are certainly less controversial.

Omniscience

Is it possible to find a single simple rule which combines the power of nishio and perfect matching, and solves perfectly all single-digit placement questions? One could, for instance, imagine a "double nishio" technique which tries setting pairs of cells instead of single cells, discovers contradictions in the consequences of such placements, uses these contradictions to deduce implications among the different placements, and remembers and uses these implications in subsequent nishio expansion phases. Or, one could add perfect matching based deductions to the expansion and contradiction phases of a nishio rule. Would that be enough to solve all single-digit problems perfectly?

I don't know the answer for 9x9 Sudoku. For larger puzzles, however, even such measures would not be sufficient. We can prove that the single-digit deduction problem is NP-complete, so we can't hope for any polynomial time rule that will always make the single-digit deductions we want it to make. To do so, we have to state the problem more formally:

Problem: Single-Digit Sudoku Deduction

Input: Set S of positions where a digit D may be placed in an N2xN2 Sudoku board; position RiCj in S to be tested.

Output: Yes if there exists a set of placements of D in positions of S, covering all rows, columns, and squares of the board and including position RiCj; no otherwise.

Theorem: Single-Digit Sudoku Deduction is NP-complete.

Proof sketch: Clearly it's in NP. To show NP-hardness, we reduce from a modified version of 3-SAT, in which we are given a 3-SAT formula F, a satisfying assignment S, and a variable v0, and must determine whether there is a satisfying assignment for F in which the value of v0 is different than its value in S. It's easy to transform the standard 3-SAT problem into this modified form, by adding a new variable v0 to a given 3-SAT instance, including it in positive form in all clauses (turning the instance into a 4-SAT instance with known satisfiable assignment in which v0=true), then applying the standard anti-resolution trick for splitting 4-clauses into 3-clauses.

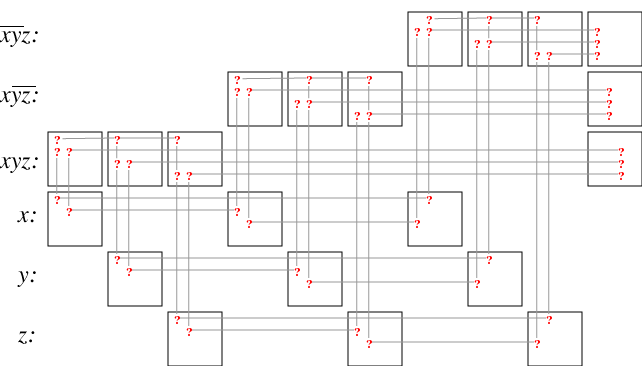

To transform the modified 3-SAT instance into an instance of Single-Digit Sudoku Deduction, we create a gadget per variable consisting of a set of positions in a horizontal sequence of squares, two positions per square and two positions per row, so that there are only two consistent ways of placing the digit, one (which we associate with assignments of the value true to the variable) using the even positions in this set and the other (which we associate with assignments of the value false to the variable) using the odd positions. We also make a gadget per clause consisting of a horizontal sequence of four squares, one for each term of the clause and one terminal squares. We place three positions in each of these squares, so that a certain row R can only be covered if one of the variables is assigned true, and so that the other three rows used by these gadgets can always be covered. Finally we fill in the remaining squares of the board with positions of S not belonging to the rows and columns used by these gadgets. A schematic view of this reduction is shown below.

Where Do We Go From Here?

We have seen that extending nishio until it reaches perfection is an ultimately futile goal. And anyway I prefer to avoid adding anything resembling nishio to my program, as I prefer to stick to rules that can clearly be justified as pattern-matching-based deduction without trial and error. But I would like my program to be able to solve the first example above.

In that example, and in similar examples I've seen, the positions of the digit have a very specific pattern: a set of evenly many squares of the puzzle (four or six for 9x9 Sudoku), with the positions within each square limited to two rows and two columns, and the positions within each row or column limited to two squares. For such restricted positions, I think it should be possible to solve the single-digit deduction problem perfectly with a polynomial time algorithm that does not employ trial and error, but I still need to work out the details before adding it to my program.

In the meantime I should add some of this material to my Sudoku paper. But probably in much more concise form, since it's off-topic for the graph path search and non-local Sudoku rule ideas in that paper.

ETA 2005-10-11:

Via an email exchange with Robin Gatter, I realized that some of these issues can be solved by extending my nonrepetitive path analysis to allow paths in the bilocal graph with odd numbers of repetitions. E.g., in the first example above, the path R7C5-R3C5-R1C6-R1C7 (three repetitions of the same label) starts and ends with the same label, so the bilocal path rule allows us to eliminate the square R7C7 which conflicts with both endpoints of the path. The single-digit versions of these rules would be:

- path

- Draw a graph connecting two cells whenever the given digit's location within a row, column, or square is forced to lie only in those two cells. If cells x and y are connected in this graph by an odd-length path, then the digit can not be placed at any cell that conflicts with both x and y.

- conflict

- In the same graph as above, suppose that a cell x is connected by odd-length paths to a set of cells S such that the members of S together conflict with all possible locations for the digit in some row, column, or square of the puzzle. Then the digit must be placed at x.

(The other case of the conflict rule is already covered by the path rule, and the other nonrepetitive path analysis rules require more than one digit in their paths to do anything useful.)

I'm tempted both to implement the single-digit path rule (since it looks well within human solver capabilities) and to add odd repetitions to all of my bilocal graph analysis rules (to maximize the power of my program while still using rules explainable as deductive pattern matching).